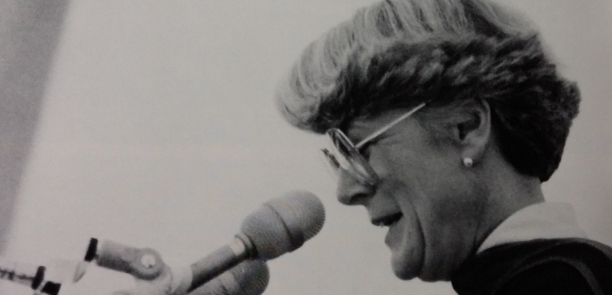

Geraldine Ferraro's Commencement Address to the Wellesley College class of 1985

Geraldine Ferraro's Commencement Address to the Wellesley College class of 1985

New Doors, New Directions: Facing America’s challenges in a changing World

Thank you, Dr. Keohane for that kind introduction I am very glad to be here in Wellesley this morning. I must say, it is wonderful to be in a place that already has a woman President. I understand that when Wellesley was founded, one fellow objected that “vigorous study will prove too strenuous for the feminine mind and condition.” I just want you to know I ran into a few of his relatives and they didn’t think a woman could run for a national office, and I’m glad you and I have proven him wrong.

But what makes me happy, as I look out from the podium today, is knowing that I’m not just looking at a graduating class, I’m looking at part of a return on my generation’s investment in the future. You, like thousands of other graduates throughout the country, are the most valuable resource our nation has. Your years at Wellesley have given you a voice in our future, and equipped you for the tasks our nation will face in the years to come.

The liberal arts training that you have received is probably the single most important tool our nation can have to help us face tomorrow. You have acquired the ability to think. You have learned to analyze and research. You have learned to separate fact from fiction, to gather data and understand what it tells you. You have met the thinkers who have built our history and our culture. You have learned, not just to make a living, but to make a life.

But I hope that’s not all Wellesley gave you. I hope it gave you the vision to see beyond yourselves; that sometime in these past four years, somewhere between meeting your first Ask-Me and sitting down to the champagne breakfast, you have taken the time to ask the larger questions.

I am confident that Wellesley has taught you to see yourselves as part of a larger community. Not just as women, or as Americans, but as global citizens. If our country is to survive, we can no longer stand isolated. Today we are entirely interdependent on other nation’s well being. This is true economically, scientifically, and culturally.

This means new directions for all us all, and new doors opening up. Those of you graduating today have been raised as members in a global family. In the next years, you will have more knowledge of, and more contact with, people in other nations than any generation in history. Your lives will be richer for that. That contact will bring you economic and scientific progress, and exciting cultural discoveries.

It also brings new responsibilities. To be concerned not just about ourselves, but about each other.

The problems that will face us tomorrow demand solutions that transcend our borders and national interests. We need a long-range perspective, one that looks beyond what will solve today’s crisis to what will build tomorrow’s society. Nowhere is this wider view more important than in our nation’s foreign policy.

I recently returned from a three-week trip to Europe, where I met with several heads of state. I spoke in detail with defense and finance ministers and foreign secretaries of our NATO allies. Today want to share with you some of what I found on that trip.

We are a strong coalition because we hold strong principles, NATO began as a union to build and defend the values that our countries hold in common. Together, we support the ideal of a participatory democracy. We believe in the free competition of ideas. Above all, we have a firm commitment to human rights.

Of course we have disagreements. Those I talked with stressed that the United States must work to maintain a partnership of equals. They pointed out that being friends means we must ask before we act. They are unhappy when we move unilaterally, when we impose sanctions without consulting them, as President Reagan recently did in Nicaragua. Only by cooperating fully can we get their help for programs we all need. They expect to be partners in fact, not after it – and they are right.

As I look to our future as global citizens, I am most concerned about our relationship with the Soviet Union, the issue I considered most important in my campaign. We must have no illusions in dealing with them. They are our chief adversary. Their totalitarian system is based on values which are repugnant to us as a free nation.

But I remember reading in the papers an interchange that occurred between a Western reporter and a Czechoslovakian farmer after Russians invaded that country. The reporter asked if the Czech viewed the Soviets as friends or brothers. The farmer didn’t hesitate: “Brothers, of course. You choose your friends.”

We are today in the same position as that farmer. We do not like what the Soviets stand for, and we are opposed to much of what they do. But we do share a globe with them. In the years to come, our challenge is to find areas of common concern, where we can work together to build bridges between our nations. We must learn to cooperate where we can, and compete where we must: in the free flow of ideas and the realm of human rights.

I know we can do better. Last month, President Reagan went on a trip to Europe to mark the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II. His visit to Bitburg was a sorry and insensitive slight to all of us who recognize the horrors of that terrible war.

But instead of going to that dark cemetery, he might have used the opportunity to mark another anniversary. Forty years ago last month, Russian and American soldiers met and shook hands at the River Elbe. It was a dramatic image of those weary men greeting each other.

But it also marked the end of our last great alliance with the Russians. We missed that anniversary, and we missed, too, a chance to send the Soviets a positive signal that we want to work at improving relations with their country. The Soviets are not like us, but neither are they ten feet tall. Our future demands more than the will to stand up to the Soviets: it also demands the wisdom to sit down with them as well.

The next few months will mark a crossroads in US-Soviet relations. Chairman Gorbachev is clearly consolidating his power. He has postponed the Communist Party Congress until February, which gives him time to marshal his forces still further. He will have an opportunity to name additional members to the Politburo and change fully one-third of the members of the Central Committee. Those signals are clear: the Soviet leadership is now in the process of drawing up a blueprint which will last five, ten, or fifteen years. That is the program that will affect us in the years ahead and we must act now to shape that policy. Again, we must look beyond ourselves, beyond our time, into the future. We must work with each other now, or risk confrontation later.

We need that long-range view in our dealings with all nations. Too often, we have found ourselves in a position of having to react – simply because we didn’t hold a vision of the future. The time has come to ally ourselves, not with the powers of repression, as we have done in so many parts of the globe, but with the ideal of liberation and empowerment.

It is our duty to become involved in human rights wherever they are being violated. As Americans, we have something in common with people everywhere who seek a greater voice in shaping their lives. Americans have always believed in the principle that nations are better off when their people are free. Those are the roots of our country, and it is what we have always stood for. Freedom has been the central theme of our great struggle to become a nation.

We must apply that standard throughout the world, whether we are dealing with our adversaries like the Soviet Union or nations we call friends, like the Philippines. America’s voice must be heard calling for human rights wherever people are oppressed, in Chile, in Haiti, in Ireland, in Cuba and in South Africa. We have a moral obligation to speak out.

American students have made their voices heard very clearly on this issue. It is tremendously impressive to see young people speaking out at universities across the country. I spoke at Hunter College in New York two days ago, where I met their student body president. It was a young woman who spearheaded the successful effort to make the entire City University of New York system divest its South African holdings. We have seen such actions at Yale, at Columbia, and here at Wellesley. I congratulate those of you here at Wellesley who successfully worked with your Committee for Social Responsibility to urge divestment in companies who refuse to abide by the Sullivan principles, and I thank you for wearing those white armbands today.

This is global citizenry at work. When we expand our actions beyond our own concerns, we do more than just focus attention on the problem. People get involved. They learned that when we raise our voices together, we are heard.

Our moral convictions inspire us to speak out, but it is also in our national interest to do so. The United States cannot ally itself with powers of repression in South Africa; it is clear that the majority rule will come into that country. We cannot interfere with the self-governance of our Central American neighbors; it is clear they will take their own road to development. Nor can we stay silent when there are prisoners of conscience in jails in the Soviet Union, for it is clear that some day their voices will be heard.

As we look for new opportunities in that direction, let me make a suggestion. We will soon have a perfect opportunity to stand up for these principles. This summer marks the 10-year anniversary of the signing of the Helsinki Accords. Those accords were a landmark stand in our fight for human rights in the Soviet bloc countries. Let’s not miss that anniversary. Let us use it to reaffirm what American has always stood for: the right of all people to be free. That is the path of our future.

There are new opportunities, too, for human rights in our own country, and that was the message of our campaign. We did not win the election, but we did win something very important: a victory of spirit that will help our country face the future. We broke down an unjust and unwise barrier. The night he chose me, Walter Mondale opened up a door that will never again be closed. By putting a woman on the national ticket, we declared that the tyranny of expectations is over.

My campaign was part of a larger shift in our society, one landmark in an age of important landmarks for women. Now we have had the first woman in space, the first woman on the United States Supreme Court, the first women on the national ticket of a major party, the first woman ever to win the 18-day dog sled race in Alaska, and just last month the first woman to be ordained as a conservative rabbi. Not to mention the first women’s rowing crew in the nation, right here at Wellesley.

Why this breaking of barriers everywhere at once? Because, in my opinion, there is so much unfortunate history to break with and repudiate – a history of unequal treatment and low expectations for women.

When I was about to go to college, my uncle said to my mother: “Don’t bother, Antonetta, she’s pretty, she’ll get married.” Well, I was…and I did. I am only sorry that he didn’t live to see that niece nominated for the second highest office in the land.

When I applied to law school, a university official asked if I was “serious” – because, after all, I was taking a man’s place. Today, no professor would be caught dead saying that to a female student. First of all, that professor could be a woman. In fact, if she were at Wellesley, you can bet her Department Chair would be a woman. More important, the greatest achievement of the woman’s movement has been to transform our expectations.

Today, in America, women can be whatever we want to be. We can walk in space, and help our children take their first steps. We can run a corporation and work as wives and mothers. We can be doctors and we can teach our six-year-old children how to bake cookies.

Or we can choose none of these. We don’t have to be superwomen. For the first 14 years of my marriage, I worked at home as a mother and wife. That was a fine profession, and nothing I have done since has filled me with more pride and satisfaction. For me, it was the right thing. Then I decided to work outside the home, and that was also the right decision for me. Not every woman would agree with my decisions, but the point is, they were mine – I made them for myself. I know that every woman can take pride in whatever she chooses to do.

No school understands better than this one. For more than a century, you have made history for women. For a decade, your Center for Research on Women has been doing fine work in areas like education, employment, and minorities. Only twelve years ago, there was no law guaranteeing a woman’s right to compete in school athletics. This fall, Wellesley will dedicate its own spectacular women’s sports complex. Even the most sacred Wellesley traditions reflect the new options open to women: I understand Hoop Rolling now helps your career, not just your marital status.

That freedom isn’t just good news for women, it’s good news for all Americans. I believe that a nation can only be great by using all of the talents and all of the energy of all of its citizens.

I’m not speaking just to women today. You don’t have to be women to be a woman to be offended by discrimination. Most men are. Every father is diminished when his daughter is denied a fair chance. Every son is a victim when his mother is denied fair pay. The fact is that when we lower barriers, when we open doors, we free all of us to reach wherever our dreams will take us.

Let me share a letter I received from a Rhode Island woman with two young daughters, aged four and two. “I brought my two daughters to a rally in Providence, because I wanted them to see you. I wanted them to know what they could aspire to, that the possibilities for them were limitless, that they could, if they wanted, be President, and that being female would not preclude them from doing or being any they chose.”

That was really what our campaign was all about – making America the best it can be by using the talents of every American. And that is why, whatever else happened in 1984, I will never regret the campaign. It was a gain, not just for women – it was a plus for all Americans. We took down that sign that said “Men Only” on the door to the White House. That was more than just and idea for 1984 – that was an ideal to carry us to the year 2000 and beyond.

I spoke in Seattle two weeks ago, in a room packed with 1150 women. Afterwards, a young girl spoke up. She said: “I’m 17 years old, and when I hear you list women’s accomplishments in the last few years, I just wonder what will still be left for my generation to do?” (In response to a laugh from the audience, Ferraro then extemporized a remark to the effect that it was a good thing no conservatives were present because the audience’s reaction would have upset them.)

To me, that question symbolized where we are as women in 1985: we’ve made enough progress so that young women take so many things for granted. The fact that any 17-year old can honestly look around her life and wonder “what’s left” is a tribute to a lot of hard work.

But we can’t stop there. We must continue those strides, broadening our horizons and our hopes. I remind you of what I reminded her: The good is the enemy of the better, and still greater enemy of the best. We talked for a few minutes about Equal Rights Amendment, and about comparable pay and pay equity, and all the other vital issues facing us as women in 1985. I think, when we finished, she was relieved to find that her generation just might have one or two battles left to fight.

And that is my message to you today. You are free to rise as high as your dreams will take you. Your task is to build the future of this country and of our world. You are our new global citizens. Whatever you do, I remind each of you that your potential and possibilities at this juncture of your lives are absolutely limitless.

Wellesley has given you the skills to make this world a better place. It has offered you the vision to make it more human. For my part, I wish you the courage to stand up for what you believe in. I know there are new doors ahead for our country, and I hope we’ll go through them together. With your help, I look forward to seeing what lies beyond them. Congratulations and good luck.