Free and open to all from Tuesday to Sunday 11 AM to 5 PM. The Davis is closed on Mondays and holidays.

Sinner and Saint

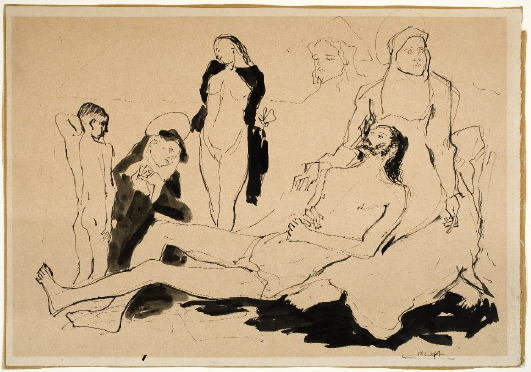

Jose Bover Benasser (Palma de Mallorca, Spain 1921 – Felanitx, Spain 1996), Deposition, Mid. 20th century, Pen and brush and black India ink, 34.7 x 50 cm, 1995.55.

Also known as Josep Bover Bennàssar and José Bover Bennassar, Josep Bover Bennàssar's enigmatic drawing expresses the ambiguity specific to Mary Magdalene. It represents the deposition of the body of Christ after his death on the cross. The Virgin of Sorrows has her son's head on her lap. The naked child placed at the feet of the dead may evoke the allegory of innocence that mourns this sacrifice. The two women draped in black could be the other two Marys at the crucifixion – Mary Magdalene and Mary of Clopas. They may also be a double evocation of Mary Magdalene. The first, kneeling at the feet of Jesus in the iconographic tradition of deplorative scenes, is dressed as a nun, her head framed by a halo and her hands joined in prayer. She could represent the holy aspect of this figure, and the spiritual, celestial love she feels for Christ. The second woman, standing upright, with her head turned and her hair and body exposed, would then evoke the sensual aspect of Mary Magdalene, and her carnal, earthly love.

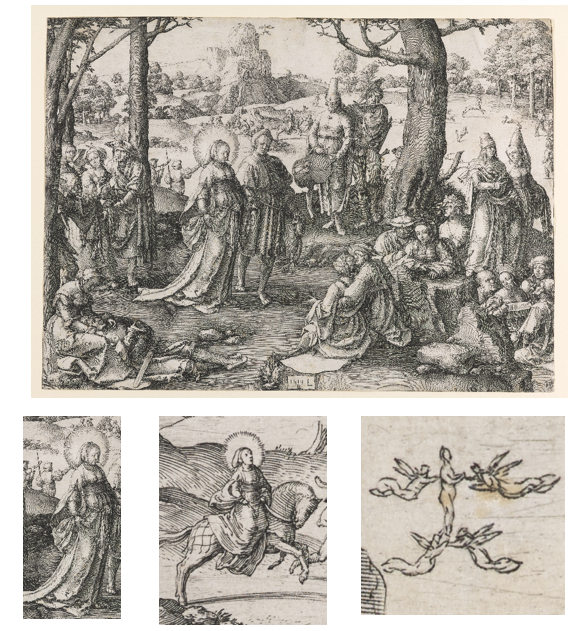

Lucas van Leyden (c. 1494-1533), Dance of Mary Magdalene, 1519, Engraving, 40 x 48.4 cm, 1961.1.

Mary Magdalene’s reputation as a courtesan has a long history. In the fourth century, Pseudo-Basil of Caesarea quoted the Christian bishop Amphilochius of Iconium in one of his homilies. According to this, Amphilochius already had described Mary Magdalene as a sinner and a prostitute. In Dance of Mary Magdalene, Lucas van Leyden invented a new iconography to address old ideas about the saint. This engraving presents the saint's life in three episodes. Although Mary Magdalene is the only character with a halo, the artist also insisted on her worldly sensuality in the foreground. Surrounded by couples and musicians, she holds the hand of a noble man. At the intermediate level, Mary Magdalene hunts on horseback, in another expression of her life of pleasure. Finally, in the background, van Leyden represented the assumption of the saint carried by the angels, although it is not visible in this version. In other copies of the print, van Leyden thus creates a trajectory between the courtesan and the repentant, insisting on the need for penance.

Lucas van Leyden (c. 1494 – 1533), The Dance of St. Mary Magdalene and details, 1519, engraving, Sheet (cut within platemark): 11 5/16 × 15 1/2 inches (28.7 × 39.4 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the Alice Newton Osborn Fund, the Lola Downin Peck Fund, the Print Revolving Fund, and with funds contributed by various donors, 1979, 1979-65-1. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Jan Harmensz Muller, after Abraham Bloemaert, The Raising of Lazarus, 1600, Engraving, 36.5 cm x 48.3 cm, 2016.492.

In this early seventeenth century engraving, Jan Harmensz Muller reinforced Mary of Bethany's identity as a courtesan, a highly sexualized woman in luxurious clothes even after her first encounter with Christ and her conversion. This Dutch engraving represents the resurrection of Lazarus, an episode before which Jesus has already come to Bethany and met Mary. Yet, kneeling behind her brother's body on Jesus’ left, her face turned towards Christ and her hands spread out as a sign of surprise, she wears fine clothes and an elaborate hat, in great contrast to the women around her. Her round hat, in particular, contrasts with Christ's halo and other women's veils. In Harmensz Muller's view, her supposed past as a courtesan remained important even after her conversion.

Lucas van Leyden, Temptation of St. Anthony, 1509, Engraving, 18.3 x 14.6 cm, 1941.12.

As Magali Briat-Philippe has suggested in the exhibition catalog Marie Madeleine, la Passion révélée, Van Leyden might have made the surprising choice to depict Mary Magdalene as the temptress of Saint Anthony, a saint retired in the desert to pray and tempted by the Devil through visions. Recognizable by her perfume jar and courtesan’s dress, she also bears horns on her head, suggesting that she was sent by the devil to seduce and corrupt the hermit, the pious man. This kind of misogynistic image of women and their sexuality frequently appears in depictions of Magdalene’s life, including in her relationship with Christ.