Free and open to all from Tuesday to Sunday 11 AM to 5 PM. The Davis is closed on Mondays and holidays.

Imad al-Hasani, Album Page with Calligraphy, 1607, Ink, gouache and gold leaf on paper, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Donald Wilber (Margaret Surre, Class of 1927) 1994.16

Introduction: The Art of Islamic Calligraphy

Calligraphy is one of Islam’s most revered art forms, celebrated for its role in shaping diverse religious, intellectual, and cultural traditions. At the Davis Museum, three Islamic manuscript pages—dating from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries—offer a window into the evolution of this rich medium. Some pages, like these, may have been created as standalone works, while others likely originated as part of complete manuscripts or albums. Collectors often assembled new albums from individual folios or separate sheets, bringing together pages from varied origins.

Despite often being overshadowed by illustrated manuscripts, these calligraphic works reveal the intricate beauty and historical depth of the written word in Islam. The text itself conveys complex ideas and reflects a high level of artistic innovation. This exhibition invites you to explore the technical mastery and cultural significance of Islamic calligraphy across geographies and centuries through the Davis Museum’s collection.

Manuscript 1: Timurnāmeh and the Safavids

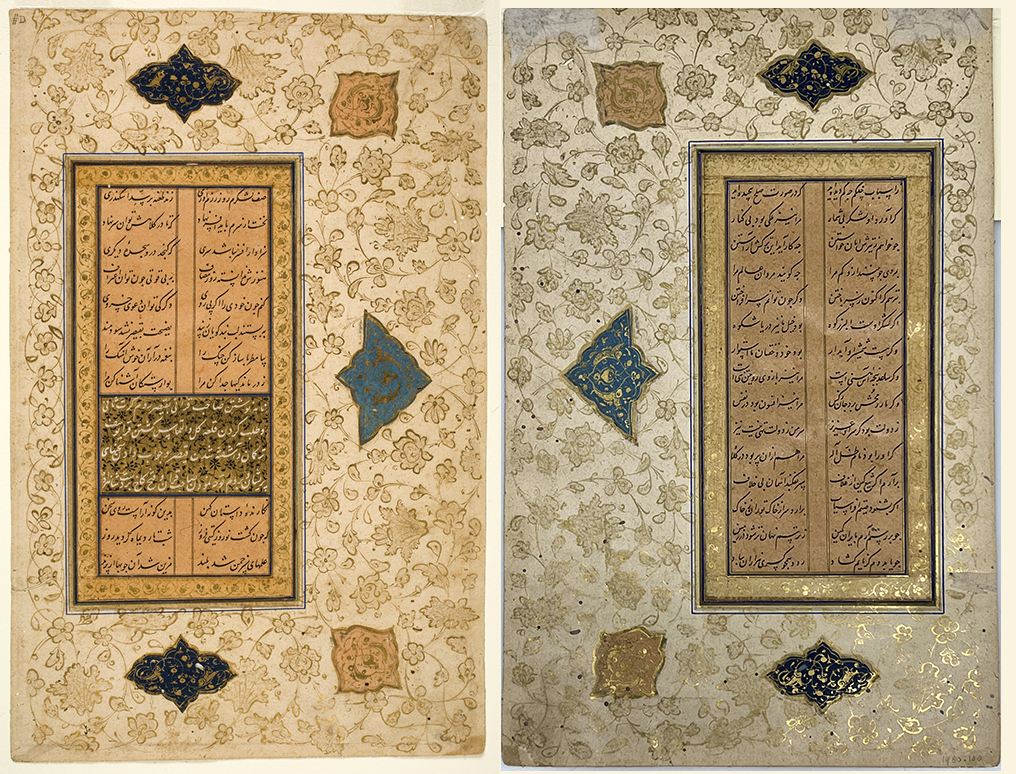

The first manuscript page from the Davis Museum, shown below, dates to the sixteenth century, during the Safavid dynasty—widely regarded as a golden age in Iranian history. During this period, calligraphy flourished as both a spiritual and artistic practice. The scribe used tempera on paper, blending water, egg, and pigments to create a richly illuminated page.

The calligraphy is framed in a rectangular box containing two columns of Persian text written in black ink. Along one side, a golden panel features thuluth script—a fluid, elegant style known for its curved and oblique lines. The background is adorned with golden lotus leaves and delicate floral motifs.

Manuscript Page with Calligraphy (2 sides), 16th century, Tempera on paper, Gift of K.C. Balderston 1980.100

The Safavid Context

The Safavid dynasty (1501–1736) unified Iran and began a period of cultural flourishing. Under Safavid rule, Shiism—a branch of Islam that holds leadership should remain within the Prophet Muhammad’s family—was established as the official religion. At the same time, Sufism, the mystical dimension of Islam, deeply influenced the arts, including literature and calligraphy.

This manuscript exemplifies the elaborate ornamentation valued during the Safavid era, a visual aesthetic that extended across various artistic media. As we will explore further below, this rich decorative style reflects both spiritual ideals and the dynasty’s broader cultural ambitions.

Motifs and Artistic Influence in the Safavid Era

This manuscript may have originated in Bukhara (now in present-day Uzbekistan), a significant center of Safavid artistic production. As reflected in the Davis Museum’s manuscript, the Bukhara school typically follows a compositional scheme in which the three outer edges of the page are richly illuminated. These borders often feature golden stylized palmettes, floral sprays, and motifs inspired by Chinese botanical forms, such as the lingzhi fungus. In this example, we also see colorful cartouches in shades of blue, dark blue, and beige. This ornamental border decoration is known as tazhib, a term derived from the Arabic word for gold, underscoring the lavish use of gold leaf in these designs.

Further evidence supporting the manuscript’s attribution to the Bukhara school lies in its presumed calligrapher, Mir ‘Ali Haravi, one of the most celebrated masters at the court of Herat (in present-day Afghanistan) until 1528. That year, he was captured by the Uzbeks and forced to relocate to Bukhara. This both forced and voluntary movement of artists explains why many scholars view the Bukhara style as an extension or evolution of the Herat tradition.

The natural motifs seen in this manuscript—palmettes, floral sprays, and peonies—appear across a variety of media from the period, including ceramics and textiles. While these motifs reveal the aesthetic ideals of the time, the manuscript also reflects the vibrant artistic production fostered under Safavid rule. It embodies not only the dynasty’s cultural pride but also the spiritual depth of the era. That spiritual significance emerges through the text and narrative—a dimension we will explore in greater detail next.

The Timurnāmeh

Understanding the significance of the text itself is essential to appreciating this manuscript. It contains an excerpt from the Timurnāmeh, a semi-legendary account of the life and conquests of Timur (ca. 1336-1405), the Mongol ruler also known as Tamerlane. Composed between 1492 and 1498 by Ḥatifi—a renowned Sufi poet active during the final years of Timurid rule and later admired by early Safavid leaders—the poem blends historical fact with myth to glorify Timur and present him as a divinely sanctioned ruler.

This manuscript offers a lens into the political and cultural context of its time, revealing how authors and artists helped construct Timur’s legacy to posthumously legitimize his power. During this period, copies of the Timurnāmeh were sometimes illustrated, with artists adding visual narratives to complement the text. In the example below, the image dominates the composition, while only a small portion of text appears—highlighting the growing importance of visual storytelling alongside the written word.

Timur Holding court in a Garden from a Manuscript of the Timurnama by Hatifi, 1551, Paintings with text; ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of John Goelet 1957.140.34

Timur sits at the center of the image, enthroned beneath a baldachin, a kind of canopy, surrounded by courtiers engaged in various courtly activities—playing music, drinking tea, and presenting gifts to the sovereign. In the upper left-hand corner, four lines of text occupy a small portion of the page, while the main body of the narrative continues on the verso.

The Timurnāmeh was a widely copied text, valued for both its literary and political significance. Mir ‘Ali Haravi, the presumed calligrapher of this manuscript, was renowned for transcribing poetic and literary works and was occasionally known to compose original pieces. In the following section, we will explore his body of work and consider the evidence supporting the attribution of the Davis Museum manuscript to this distinguished master.

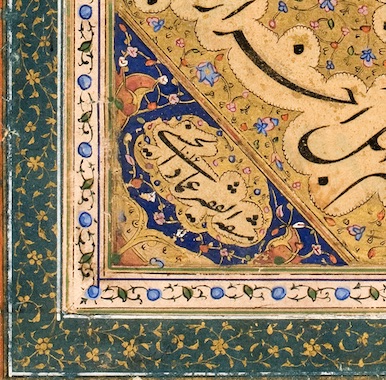

Mir Ali Haravi, Sample of Calligraphy in Persian Nasta'liq Script, 16th century, Ink, opaque watercolors, and gold on paper, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn Museum Collection X629.6

The Calligrapher: Mir ‘Ali Haravi

Mir ‘Ali Haravi, a celebrated calligrapher at the Safavid court, may have been responsible for the manuscript in the Davis Museum's collection. Ali: "A letter at the Davis Museum dated September 1980 notes: 'Authentic for the period, but attribution to Mir Ali, who was the greatest calligrapher of the sixteenth-century Safavid court, is another and more questionable point.” This assessment came from Dr. Glenn D. Lowry—then a graduate student in Islamic art at Harvard University, and now the director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City.

Haravi was especially known for his rubāʿiyāt (quatrains), four-line poems often written with a set rhyme scheme, and for his elegant and highly refined calligraphic style. His influence shaped the manuscript tradition of his era, and his legacy can be seen in many works attributed to his hand or circle.

The refined composition and script in the example from the Brooklyn Museum exemplify Haravi’s distinctive style. While we cannot confirm with certainty that the Davis manuscript was executed by Haravi himself, it may well be the work of an artist within his close circle. In the absence of a signature, definitive attribution remains elusive—but the possibility is both compelling and significant.

We can be certain that the facing page from the Brooklyn Museum was created by Mir ‘Ali Haravi, as he signed it in the lower left triangle of the composition. The decorative patterns and color palette closely resemble those in the Davis Museum’s manuscript, further supporting the possibility that Haravi—or an artist from his workshop—was responsible for its creation.

As previously mentioned, the Davis Museum holds another Safavid-period manuscript that provides valuable insight into the work of a different renowned calligrapher. We now turn to that piece to further explore the art of calligraphy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

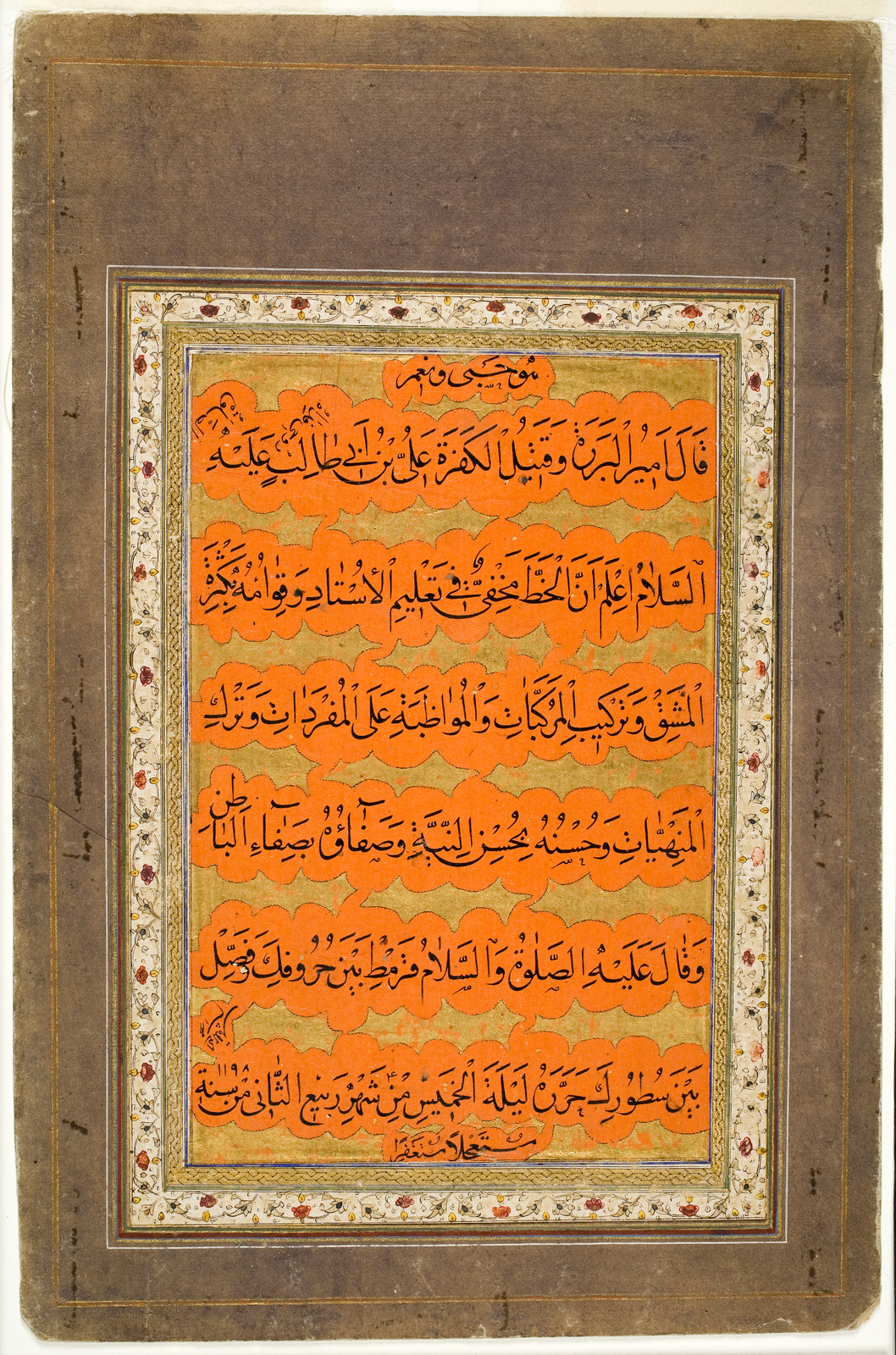

Manuscript 2: Nasta’liq poem and Imad al-Husayni’s work

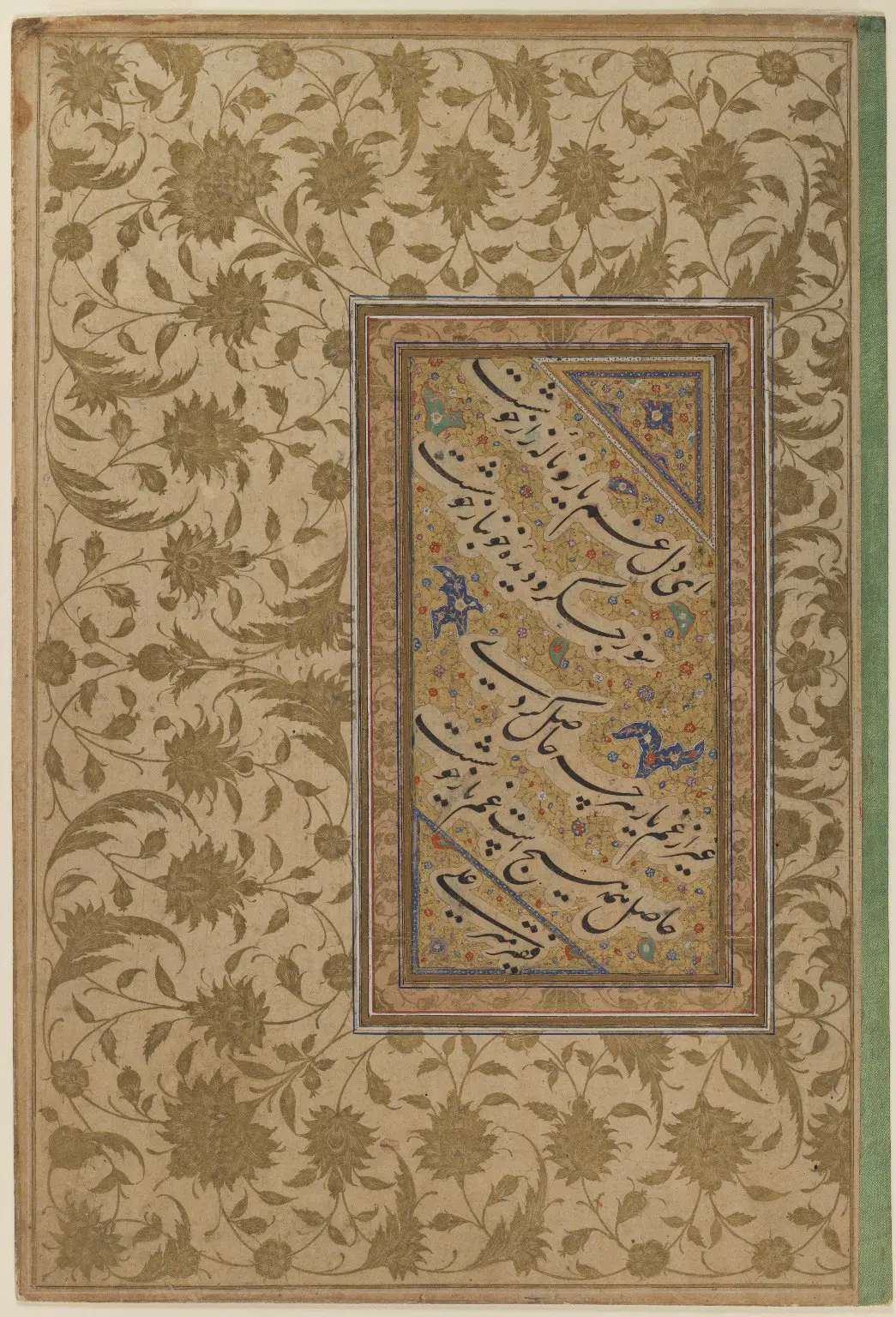

Imad al-Hasani, Album Page with Calligraphy, 1607, Ink, gouache and gold leaf on paper, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Donald Wilber (Margaret Surre, Class of 1927) 1994.16

Presentation and Style

Created in 1607, this second manuscript page is an example of Persian Nasta’liq calligraphy—a script that balances elegance with clarity. Rendered in ink, gouache, and gold leaf on paper, the calligraphy flows in a zigzag pattern that animates the words with a sense of dynamic movement. This form of writing, in which the script is set at a 45-degree angle, is called Chalipā. It is used to arrange short four-line verses known as quatrains. During the Safavid period, this style was especially prized for its refined beauty and visual rhythm. Compared to the previous manuscript from the Davis Museum, this one features more intense colors. A dark green frame highlights the calligraphic section, while the deep blue background—likely created using the costly blue pigment lapis lazuli or azurite—is adorned with small colored flowers, creating a striking contrast with the gold accents. The use of gold and costly materials and the intricate details suggest the hand of a highly skilled and important artist from the Safavid court. The text itself reveals the calligrapher ‘Imad al-Hasani's talents and way of thinking, which we explore in the next section.

The Text: A Reflection on Art and Talent

As with the previous manuscript, we begin with an analysis of the text. This manuscript from the Davis Museum contains four lines of text in the zigzag section. This text offers a timeless reflection on the pursuit of art and knowledge. Below is a line-by-line translation provided by two friends of the author: Pantea Shamgholi, a native Persian speaker who has studied Persian calligraphy, and Nazila Barghnoma, originally from Iran and currently working at the Museum of Music in Paris.

"Strive in art, for in this world,

Honor belongs to the one who possesses talent.

If no wealth comes to you from it,

At least it will rid you of the name of ignorance.”

This quatrain is perhaps an excerpt from Nasir Khusraw, a prominent eleventh-century Persian poet and philosopher. His Divan, a collection of poems, offers reflections on morality, ethics, and the pursuit of virtue. This Divan was likely chosen by the calligrapher of our manuscript, ʿImad al-Hasani, to reflect the values of the Safavid era, particularly their reverence for the art of calligraphy, which held a significant place within Sufi tradition. This remains a hypothesis.

As you can observe in the Davis Museum manuscript, there is not only text in the zigzag section. Two triangles, one on the top right corner and one on the bottom left corner, also contain text. This helps us to affirm who the calligrapher is.

Imad al-Husayni: An Important Calligrapher

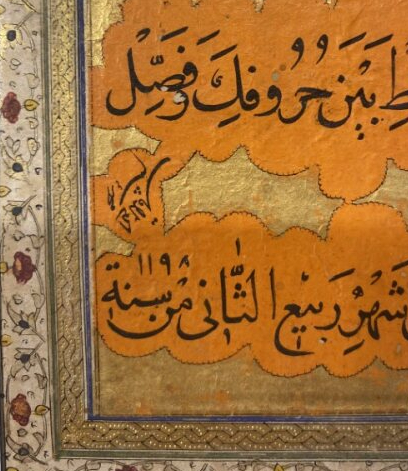

Detail - ‘Imad al-Hasani, Album Page with Calligraphy, 1607, Ink, gouache and gold leaf on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Donald Wilber (Margaret Surre, Class of 1927) 1994.16

The manuscript’s text potentially reveals much about the calligrapher and his thoughts about the importance of practicing art, as ‘Imad al-Hasani is known for several copies of texts about moral reflections on art. We have compared the Davis Museum manuscript with two others from the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art, signed by ‘Imad. These two manuscripts contain a quatrain composed by Nasir al-Din Tusi, a Persian scientist and theologian from the 13th century. The text on the two manuscripts from the Smithsonian also concerns calligraphy. It leads us to believe this may be one of ‘Imad al-Hasani’s favorite topics:

“A man with skill has at every fingertip

A key to the lock of daily sustenance.

A hand from which nothing comes

Is an incredible burden to the body”

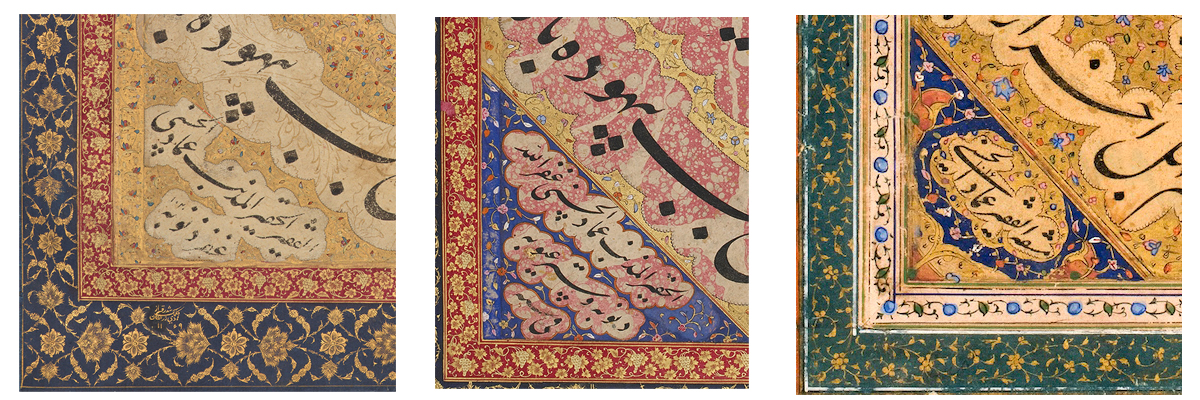

Mir ‘Imad al-Hasani (calligraphy), Muhammad Hadi Iran (borders), Folios of calligraphy, Safavid period, dated 1611–12 (1020 AH), Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, purchase Freer Gallery of Art F1931.20 and F1942.15b

Detail - ‘Imad al-Hasani, Album Page with Calligraphy, 1607, Ink, gouache, and gold leaf on paper, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Donald Wilber (Margaret Surre, Class of 1927) 1994.16

In the first two images, which form a pair, we can observe the signature of Mir ‘Imad al-Hasani. Compared to our manuscript, shown on the left, the surrounding inscription that accompanies ‘Imad’s name can vary. In the first detail, the calligrapher has also included the date “۱۰۲۰” 1020 AH (1611–12 CE in the Gregorian calendar). Mir ‘Imad al-Hasani established a renowned school of calligraphy in Isfahan (in modern-day Iran). While he primarily copied significant texts of his time, he also composed poetry, although only a few of his poetic works survive today.

Tragically, ‘Imad al-Hasani's life was cut short around 1615 in Isfahan (a major city in modern Iran), when he was murdered in the midst of larger political and religious conflicts. There are different hypotheses about his death. He might have been murdered because of his jealousy of his rival Ali Riza, another Safavid calligrapher. A second hypothesis is that ‘Imad was part of a sectarian movement. He was a practicing Sunni and adhered to the Naqshbandi Sufi order, a movement fundamentally opposed to the Safavids’ emphasis on a strong Shi‘i-oriented Sufi tradition. Nevertheless, his work was highly acclaimed during his lifetime, thanks to the prestige of his school and the many pupils he trained, including his daughter. Some scholars consider his style to represent the height of perfection in Persian calligraphy.

Thanks to these two calligraphy pages from the Davis Museum that we have examined, we now have a deeper understanding of Persian calligraphy and two of its foremost artists during the Safavid era. The next manuscript comes from a completely different context in terms of language, script, period, and geographic origin.

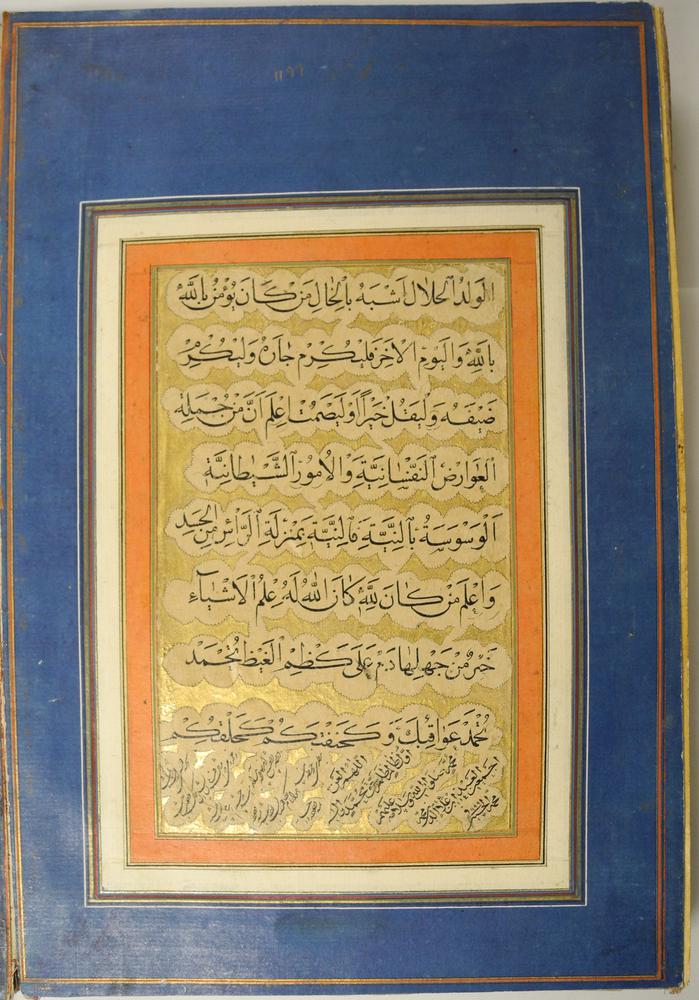

Manuscript 3: Arabic Calligraphy in the 18th Century

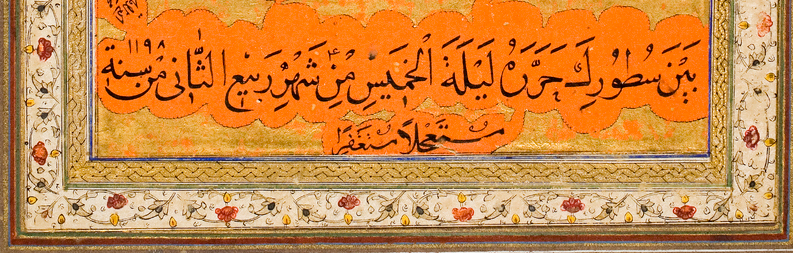

Muhammad Hashim, Manuscript Page from the Kitab Ali, 18th century, ink, gouache and gold on paper, Gift of Mrs. Toivo Laminan (Margaret Chamberlin, Class of 1929) 1962.20

Presentation and Context

The final manuscript, dating to the eighteenth century, is written in Arabic Naskh script, known for its clarity and precision. Likely part of an album, his page is intricately designed with "cloud bands" or "bubbles" framing the text. There are also several delicate elements, such as small pink, yellow, and blue flowers scattered around the frame, as well as a secondary border composed of intricate geometric lines.

Concerning the colors of this manuscript, we can observe a particularly bright and vibrant orange. This hue is produced using minium, a pigment known for its intense tone. The orange is further enhanced by the presence of gold, which adds depth and richness. Upon closer inspection, the gilded areas reveal fine cracks, indicating the use of a binding agent such as gum arabic or an egg-based preparation to ensure better adhesion to the paper. These subtle details are almost not visible to the naked eye and only become apparent when zooming in.

This particular color may hint at the manuscript’s origin, possibly North India. According to a video made by the Getty Museum, Exploring Color in Mughal Paintings, Mughal artists—who worked in a flourishing dynasty in North India—frequently used this orange pigment in their works. We will explore this possible attribution to the Mughal dynasty in more detail later. As with the two previous manuscripts, we will begin by taking a closer look at the text written in that manuscript.

The Text: Calligraphy as a Divine Art

As you can observe in the manuscript from the Davis Museum, the text is written in black ink. It is an excerpt from the Kitab Ali, a sacred text attributed to ʿAli ibn Abi Ṭālib, the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad. ʿAli is traditionally regarded as the originator and founder of Islamic calligraphy. In this passage featured on the Davis Museum page, the poetical text reflects on the spiritual dimension of the art form, highlighting the importance of perseverance, the purity of intention, and the essential role of divine guidance in achieving mastery:

"Know that calligraphy (khatt) is concealed in the master’s teaching.

Its foundation lies in hard work and the practice of words,

Its beauty lies in the purity of intention,

And its purity in the purity of the innermost part (Bāṭin)."

(This translation was provided by Dr. Louise Marlow, Professor of Religious Studies and former Director of Middle Eastern Studies at Wellesley College.)

This excerpt, inscribed in the Davis Museum manuscript, also serves as a personal reflection by the artist on his craft. The artist, Muhammad Hashim, may have been a master calligrapher. We will now examine his work more closely through this same manuscript page.

Calligraphy as a Divine Practice

Detail of the signature - Muhammad Hashim, Manuscript Page from the Kitab Ali, 18th century, ink, gouache and gold on paper, Gift of Mrs. Toivo Laminan (Margaret Chamberlin, Class of 1929) 1962.20

The calligrapher of the Davis Museum manuscript, Muhammad Hashim, signed his work, as seen in the detail. He used a distinctive and inverted form of calligraphy. Although the signature is very small and placed discreetly between two lines, the script remains highly meticulous. This refined execution may have been a deliberate demonstration of his skill and artistic mastery.

The second to last line of the manuscript reads: “The least of God’s servants Muhammad Hashim executed it the night of the 5th of Rabi II in the year 1198.”, as you can see in the detail below. He also added a phrase after the text, which we call a colophon. We can read "Urgently seeking forgiveness" (the very last smaller line in the detail below) — a powerful acknowledgement of human imperfection and the need for divine mercy. He seems to be very modest about his work.

Detail of the last line and the colophon - Muhammad Hashim, Manuscript Page from the Kitab Ali, 18th century, ink, gouache and gold on paper, Gift of Mrs. Toivo Laminan (Margaret Chamberlin, Class of 1929) 1962.20

Thanks to the signature and date, we can situate the Davis Museum manuscript within a specific period and geographic region of the Mughal Empire. As mentioned in our introduction, several key elements point to a Mughal origin for this manuscript. In the following section, we will explain the evidence that supports this attribution.

The Mughal Connection

The inscription we saw just before on the last line of the text dates the Davis Museum manuscript to "the night of the 5th of Rabiʿ II in the year 1198" (1784 CE), placing it within the later years of the Mughal Empire. Known for its deep appreciation of the arts, the Mughal dynasty played a key role in shaping Islamic calligraphy during the eighteenth century. The manuscript’s Indian motifs include small, delicate flowers on the frame, and combined with Arabic script, they suggest it was created in North India, likely under Mughal rule.

For comparison, see this manuscript from the British Museum, shown below, which closely resembles ours in its calligraphy, golden background, decorative bubbles, and the vibrant orange hue we previously identified as significant in this Indian dynasty. The British Museum confirms its Mughal date and provenance.

'Ala al-dín Muḥammad al-Ḥusaín, Album page, Mughal Style - Mughal dynasty, 1784-1785 (AH 1199) (AH 1199), Materials paper, acquired by the British Museum in 1875 from Sir Charles Murray (1806-1895), British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum 1974,0617,0.15.31

Making comparisons is a valuable method for gaining deeper insight into a work of art. The use of the British Museum manuscript mentioned above helps confirm that this piece was produced under the Mughal dynasty and sheds light on the artistic practices of Mughal artists.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Islamic Calligraphy

The three manuscripts from the Davis Museum in this exhibition trace the rich history and evolution of Persian and Arabic calligraphy in the Muslim world. Spanning the sixteenth century during the Timurid and Safavid periods through the eighteenth century in North India under the Mughals, each page reflects the cultural, political, and spiritual forces that shaped its creation. The text, the calligrapher’s signature, and the use of color all help situate these works within the broader tradition of Islamic art. Today, Persian and Arabic calligraphy remain vibrant cultural practices around the world, with each artwork serving as a powerful testament to the enduring beauty and significance of the written word.

This exhibition is curated by Clara Piantino, 2025 Liliane Pingoud Soriano ’49 Curatorial Fellow and MA student at the École du Louvre.