Free and open to all from Tuesday to Sunday 11 AM to 5 PM. The Davis is closed on Mondays and holidays.

Hidden Histories: Revealing the Life of a Painting was co-curated by Alicia LaTores, Friends of Art Curatorial Research Assistant, and Katherine Davies (Class of 2019), the 2019 Eleanor P. DeLorme Museum Summer Intern, and was generously supported by Peter H. and Joan Macy Kaskell (Class of 1953). This is the online version of an exhibition that is on view in the Davis Museum galleries through the fall of 2020.

Unlike anything else in the Davis’s collections, this sixteenth-century Venetian artwork was recently donated to the Davis Museum by Peter H. and Joan Macy Kaskell (Class of 1953). The painting is emblematic of a popular Venetian type during the Renaissance: the Sacra Conversazione, or “sacred conversation,” featuring the Madonna and Child surrounded by saints, and often, a donor figure.

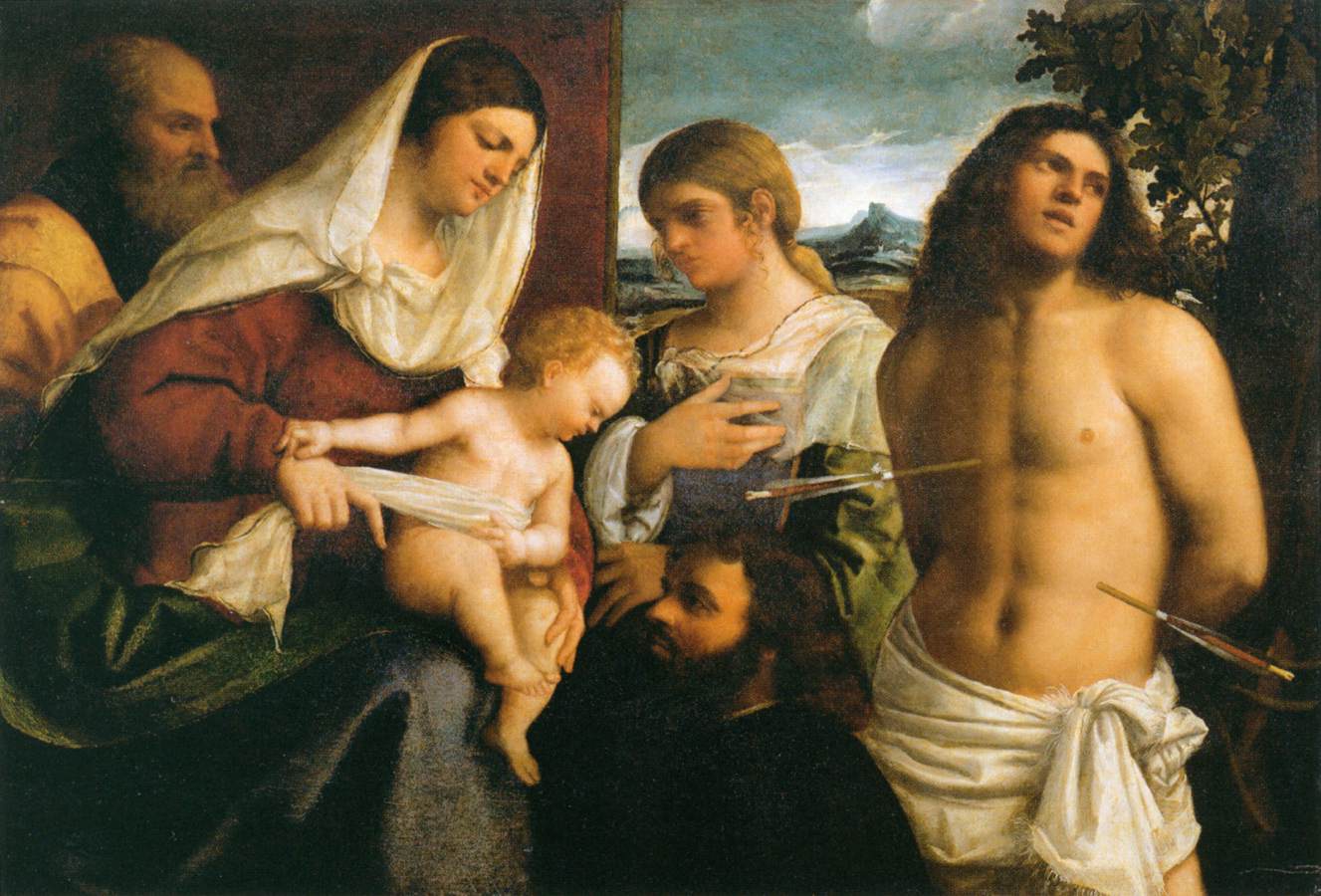

The artist of this painting is not currently known, despite its attribution to Giorgione in the nineteenth century. Other versions of the composition exist, including a painting attributed to Sebastiano del Piombo at the Musée du Louvre, Paris. Four other versions of the work include three examples in private European collections and a smaller panel in a private collection in New Orleans, Louisiana. Demonstrating the common practice for artists and their workshops to make multiple copies of a painting, the other variations are almost identical in composition, figures, and landscape. While the Davis’s panel portrays the same figural group as the other five, it differs in the landscape, which is comprised of a small town instead of a mountain, and the donor figure in the bottom center, who is a different man. In addition, areas of restoration, such as the head of Saint Joseph, are clearly visible on the canvas.

The history of visual change evident in this painting spans centuries, with multiple campaigns of restoration and conservation visible on the surface—and others hidden below. To clarify the changes and identify the original composition, a team of paintings conservators at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston undertook a broad technical analysis via UV light, infrared reflectography, x-radiography, and cross-sectioning of the paint layers, to see beneath the surface layer of paint and varnish and to construct a more complete history of the work. The results have uncovered a wealth of new information as well as highlight what is still unknown.

Venetian, Holy Family with St. Sebastian, St. Catherine, and a Donor, 16th century, Oil on cradled panel, Gift of Peter H. and Joan Macy Kaskell (Class of 1953) 2017.184

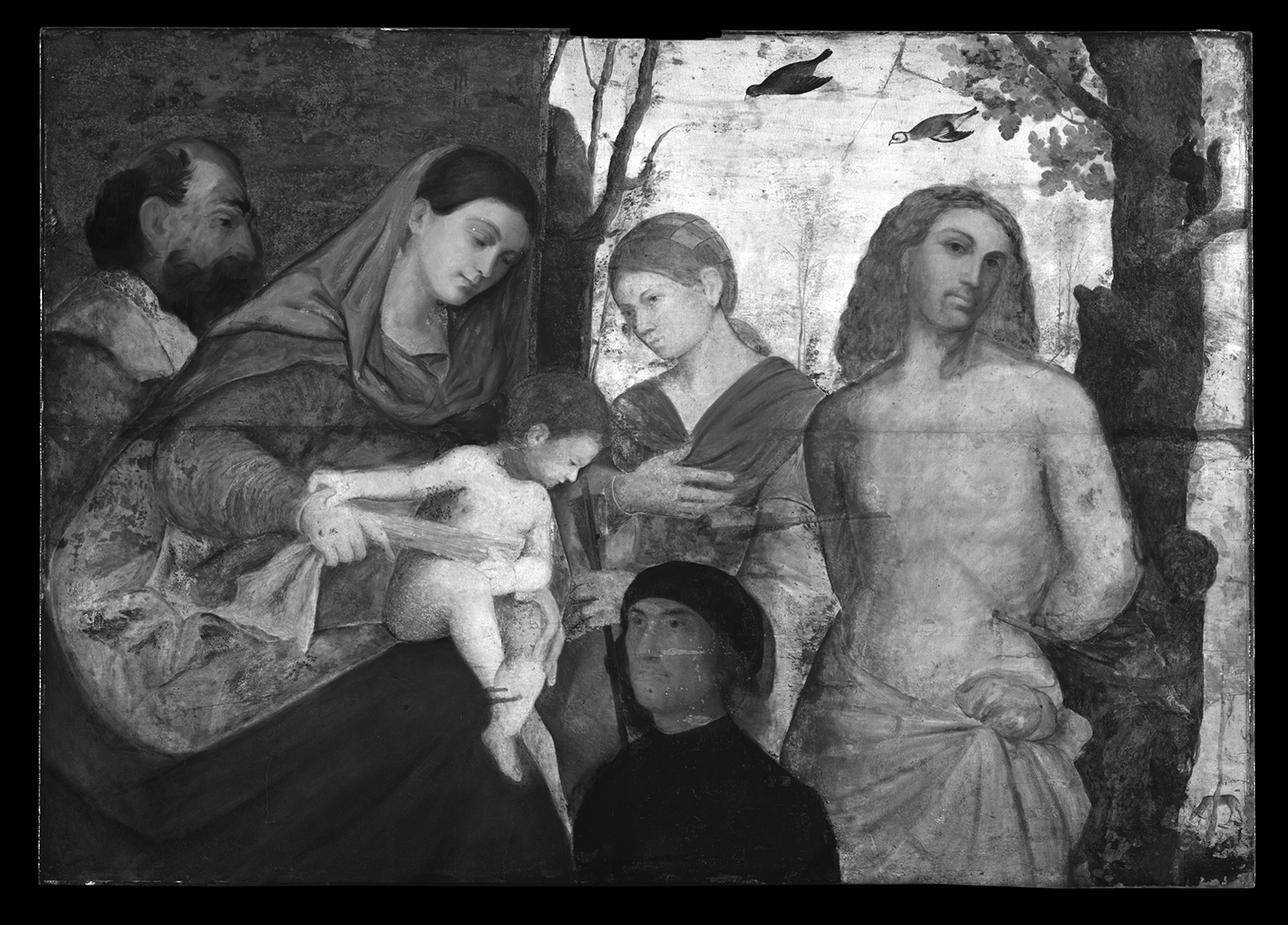

X-radiograph of the Holy Family with St. Sebastian, St. Catherine, and a Donor (2017.184).

X-radiographs use radiation to create a picture of the layers that compose a painting. Heavier substances, such as metallic pigments, block x-rays and result in white areas, whereas x-rays pass easily through paint losses, resulting in darker areas.

Worm holes in the panel have been filled with an x-ray opaque material, making stark lines across the image, and the back has been cradled for extra support, which can be seen in the gridded squares throughout the x-ray.

Infrared reflectogram of the Holy Family with St. Sebastian, St. Catherine, and a Donor (2017.184)

Similar to x-rays, infrared reflectography uses radiation to see through multiple layers of a painting. As infrared radiation is absorbed by carbon black, it is typically used to see underdrawings and preparatory sketches on the prepared surface of a painting.

The paintings conservation team at the MFA, Boston undertook a technical examination of the painting to determine if and how the surface of the work could be cleaned. They concluded that a full cleaning would reveal too much damage and an unstable surface, but the study also exposed many details that cannot be seen with the naked eye. This x-ray, reproduced above, suggests that the painting was at some point transferred to a new panel. The work exhibits minor pinpoint losses across the entire surface in both preparatory ground and paint layers and the wood grain is not visible, both of which could have occurred in the transfer process.

The x-ray confirms that changes have been made in passages that appear anachronistic, such as the overly simplified hand of the baby Jesus. The original delicately curved fingers resemble those in the version at the Louvre, which is reproduced below. The dark figure of Saint Sebastian on the x-ray indicates that lead white is not present in his torso or head, suggesting that he lacks an original paint layer and was repainted in the nineteenth century or later, when artists stopped using lead based paints.

The background of a large oak tree, flora, fauna and a delicately painted village appears relatively intact, without significant losses or overpaint, in both the infrared reflectography (above) and x-ray, marking these elements as original to the work. The landscape, including the extension of the oak tree and the teeming forest life, distinguishes the Sacra Conversazione at the Davis from all other versions, each of which features a more simplified mountain behind the figures.

Sebastiano del Piombo (Perugia, Italy 1485–1547 Siena, Italy), Sacra Conversazione: The Holy Family with Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Sebastian, and a Donor, 16th century, Oil on wood, 37 2/5 x 53 1/2 in (95 x 136 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, France. INV70

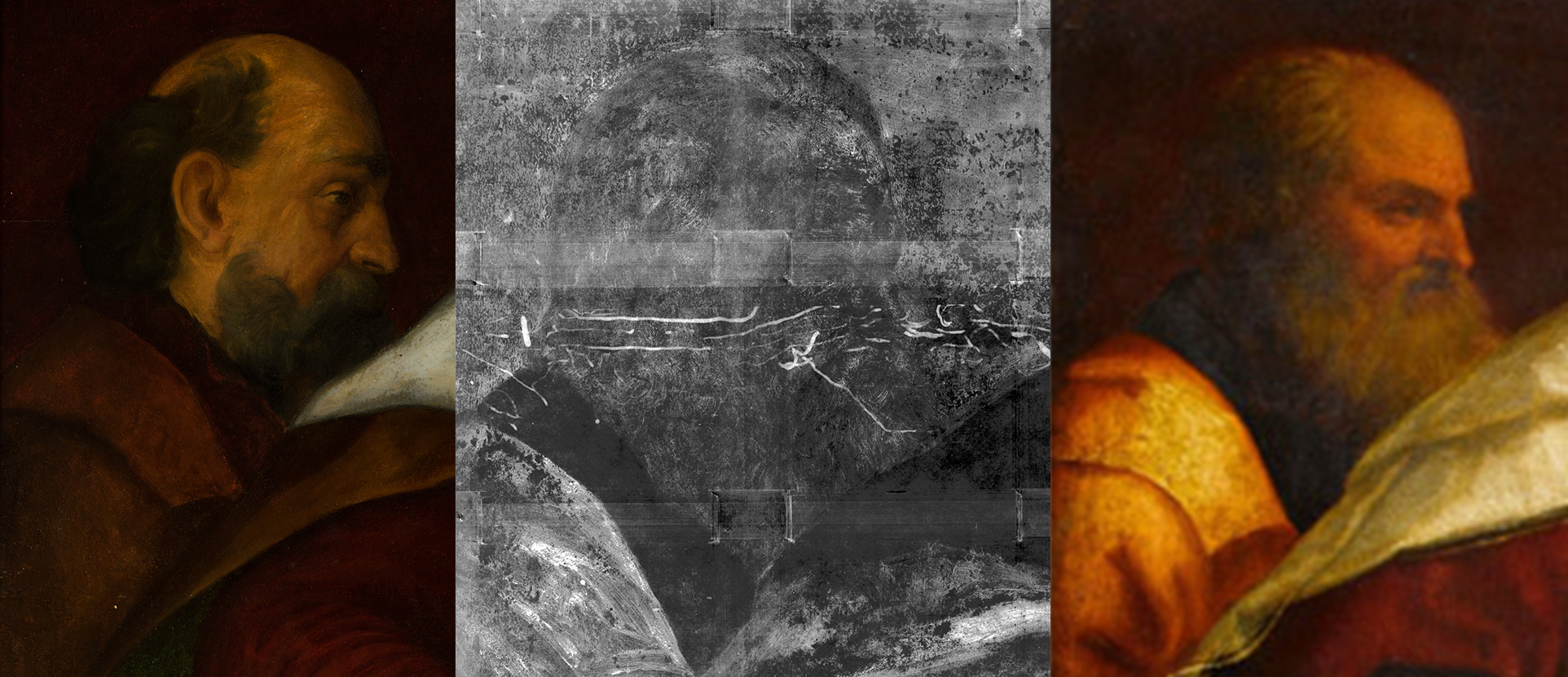

Detail images of the head of Saint Joseph, from left to right:

Holy Family with St. Sebastian, St. Catherine, and a Donor (2017.184)

X-radiograph of the Holy Family with St. Sebastian, St. Catherine, and a Donor (2017.184)

Sacra Conversazione: The Holy Family with Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Sebastian, and a Donor (Musée du Louvre, INV70).

The looser brushstrokes of the head of Saint Joseph suggest an early twentieth-century alteration. This is supported in the x-ray where he is closer in appearance to that of the Louvre figure, with longer hair and beard.

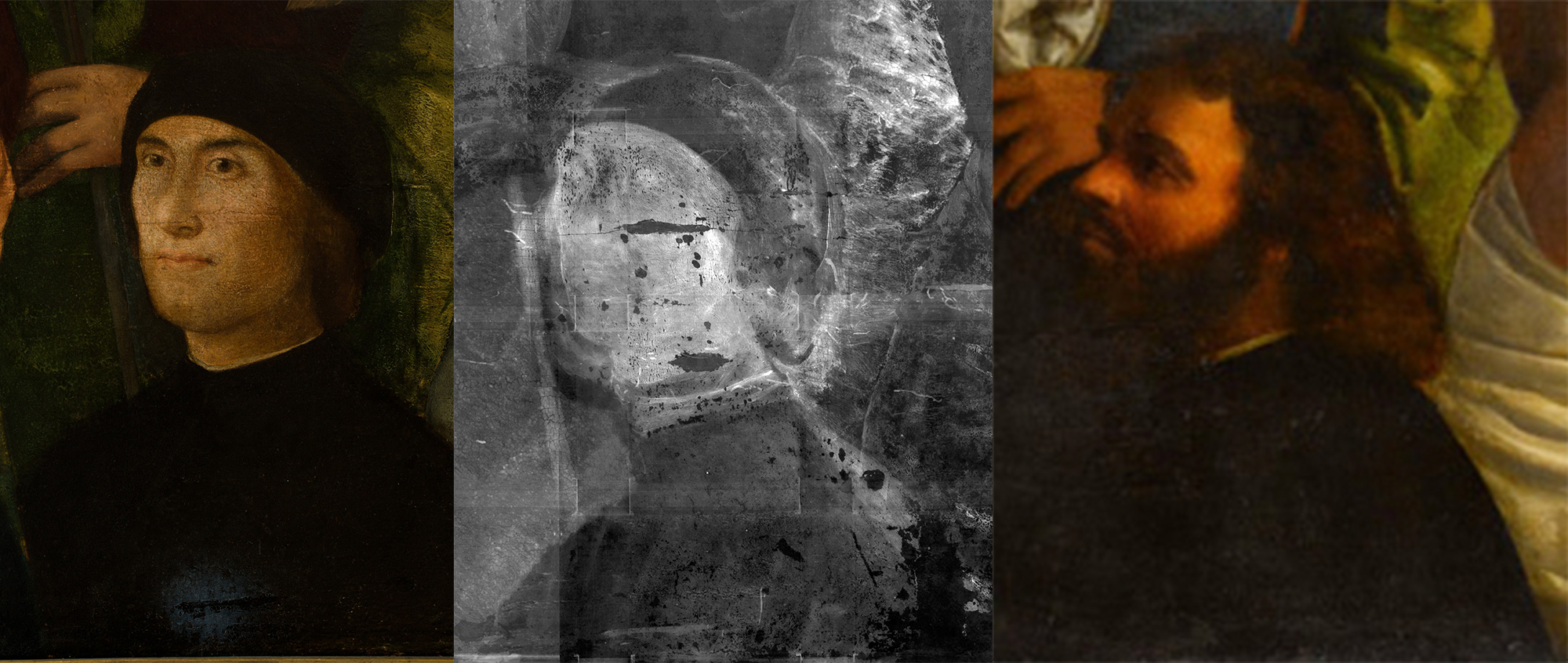

Detail images of the head of the donor, from left to right:

Holy Family with St. Sebastian, St. Catherine, and a Donor (2017.184)

X-radiograph of the Holy Family with St. Sebastian, St. Catherine, and a Donor (2017.184)

Sacra Conversazione: The Holy Family with Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Sebastian, and a Donor (Musée du Louvre, INV70).

The donor figure sets the Davis painting apart from other versions, although he appears to be nearly contemporaneous with the original work. The x-ray shows two heads for this figure: the visible capped man and, underneath, a profile that faces towards the Holy Family with longer hair, reminiscent of the donor in the Louvre painting. As the condition of the paint surface is very similar to that of the background, and there is a fair amount of lead white present in the x-ray, it was likely repainted soon after the work was created. This suggests that a new owner commissioned his own portrait to be painted on top of the original donor figure.

Provenance research has provided a rough timeline for some of the alterations. This Sacra Conversazione entered the collection of William Graham, an instrumental collector of Pre-Raphaelite art, during the nineteenth century. It is not known if Graham altered the panel, then attributed to Giorgione, an artist greatly admired by Pre-Raphaelites. At auction in London in 1886, the painting sold to Sir William James Farrer who recorded his alterations in the inventory of his collection. Farrer wrote, “The white, blue, and purple original tints of the Virgin’s robes had been repainted in grey and black. On examination I found the white and purple in good order, but the blue had been much injured and is restored.” Farrer’s account is the first known record of change to the painting. His description mentions prior restorations and provides a clue to future repainting, as the Madonna’s robes are no longer grey and black.

By 1921, the painting was in the collection of Hanns Schaeffer, owner of Schaeffer Galleries in Berlin. A photograph located in the Schaeffer Gallery archives, filed under the category of “art to be restored,” is reproduced to the right and depicts the panel’s condition after it left the Farrer collection. It reveals that Schaeffer was responsible for many changes to the painting, as Saint Sebastian and Saint Joseph differ drastically from their present appearance. In the photograph, Saint Joseph has a full head of hair, a lighter complexion, and resembles the figure in the Louvre version, while Saint Sebastian gazes to the upper right corner of the canvas, his torso lacks definition, and the drapery around his waist is noticeably shorter. Lilo Schaeffer, Hanns’ sister, and her husband Joseph Kaskell brought the work with them when they emigrated to the United States in 1938. It descended within the family to Peter and Joan Macy Kaskell, who donated it to the Davis in 2017.

Photograph of the Holy Family with St. Sebastian, St. Catherine, and a Donor (2017.184) from the Schaeffer Gallery Archives at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles and published in Bernard Berenson’s 1951 essay “A “Sacra Conversazione” in the Louvre”. The photograph, taken in 1921 or earlier, titles the painting Sacra Conversazione and attributes it to Giorgione.

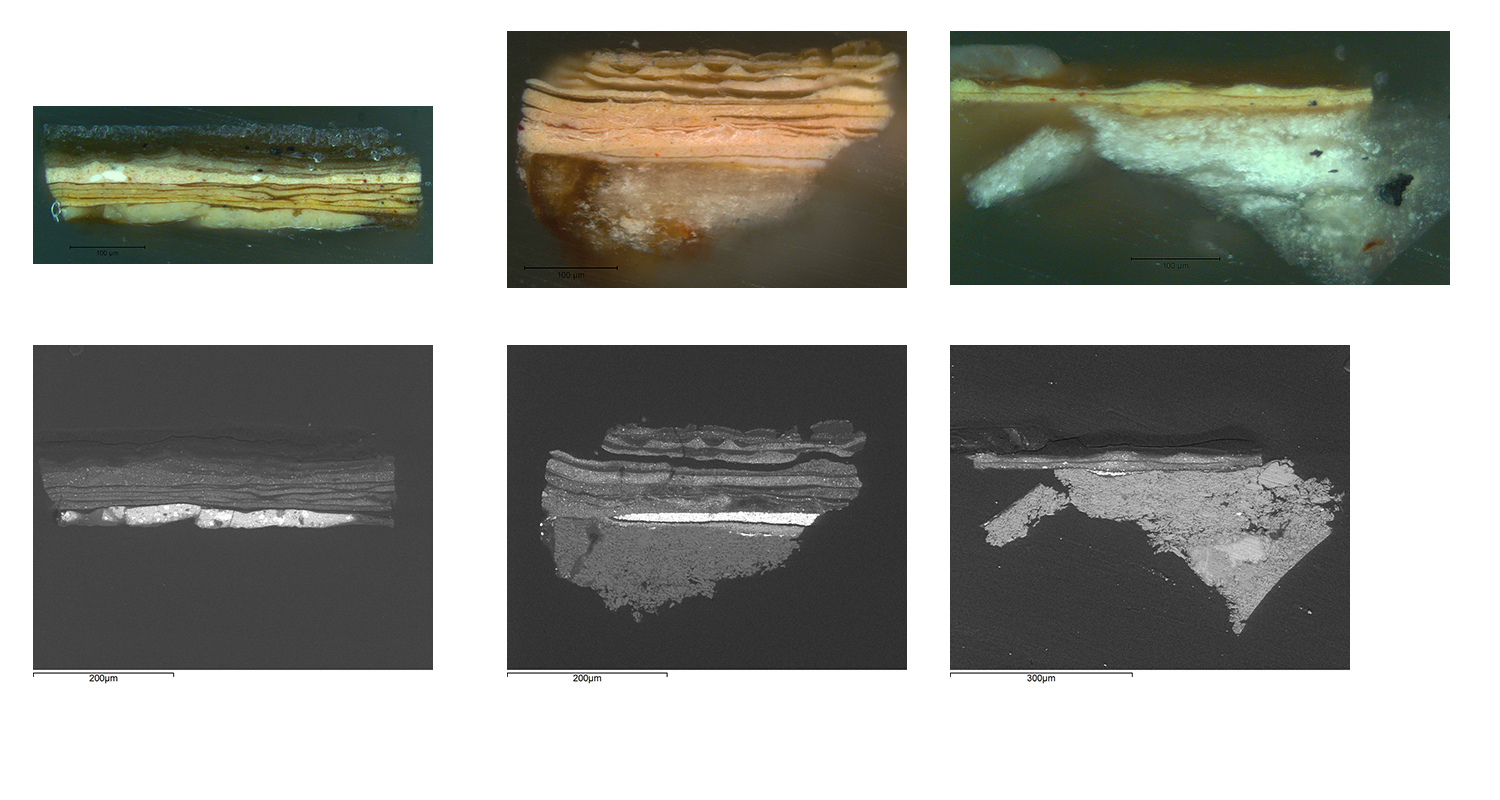

In addition to x-ray and infrared imaging, the MFA paintings conservation team analyzed tiny paint samples from the Sacra Conversazione. These samples show how much of the original paint layer survives, along with any additional layers. The samples were taken from areas where the x-rays indicated prior alterations: the Madonna, Saint Sebastian, and Saint Joseph. Cross sections of the samples are reproduced to the left. That a section from the Madonna’s forehead contains an astounding 18 layers, while Sebastian’s torso has only 6, reveals that the original paint layers vary in condition depending on the figure. The x-rays and infrared also revealed multiple positions for the Madonna’s eyes, suggesting that previous iterations survive beneath the top layer of paint. Saints Sebastian and Joseph are dark in the x-ray, which confirms more recent overpaint. This is reinforced by the sample taken from Sebastian’s torso, which indicates only three layers of paint between the varnish and gesso. Similarly, the paint samples from Joseph’s head reveal damage. There, the gesso layer is missing, and the bottom paint layer contains a consolidant sealed in place by a layer of varnish, evidence of a past restoration.

Cross sections of paint samples taken from the Holy Family with St. Sebastian, St. Catherine, and a Donor (2017.184), as viewed in dark field reflected light (top) and a back-scattered electron image taken in a scanning electron microscope (bottom). From left to right: A paint sample taken from the head of Saint Joseph, a sample from the forehead of the Madonna, and a sample from the torso of Saint Sebastian.

The x-rays and paint sample analyses confirm that this Sacra Conversazione has been transformed many times throughout the years, with the hands of multiple artists visible both on and below the surface. Ultimately, the centuries of retouching and alteration have obscured the hand of the original artist. Amidst all of the new information discovered through technical analysis, this Sacra Conversazione still holds many mysteries. Inquiry into early provenance may yet shed light on the identity of the donor figure, and further examination of the other versions would elucidate the changes apparent in the Davis painting. The five hundred years of history embedded in this panel contain many questions still to explore.