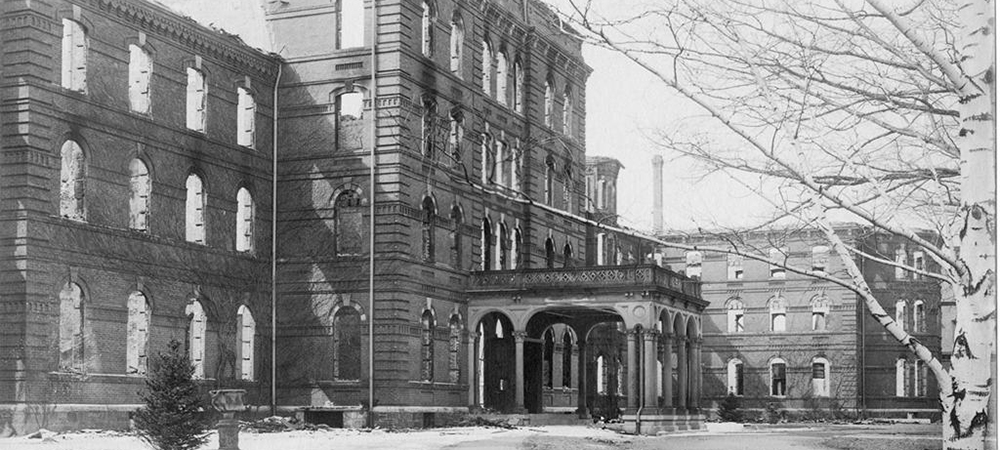

Until March 17, 1914, Wellesley’s splendid College Hall was the heart and soul of the College.

The building housed students, faculty, staff, classrooms, laboratories, art, and more, all in a single monumental edifice.

When Wellesley opened in 1875, to all eyes it was magnificent. Erected on the rise above Lake Waban, its single building was surrounded by 300 acres of a country estate with varied terrain of hills, woods, meadows, and water. The building itself was of immense size. At 475 feet in length, and rising four stories with five-story towers, it was one of the largest buildings in the United States at its opening. And it was exactly as [founder Henry] Durant wanted it—the perfect expression of the College Beautiful.

(From a “College Hall and Everything After” by Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz ’63 in a special issue of Wellesley magazine, The Night That Changed Wellesley.)

Indeed, for 39 years, College Hall was Wellesley. That immense presence overlooking Lake Waban took four years to build. But early on March 17 one hundred years ago, it took only four hours to burn.

At 4:30 a.m., up on the fourth floor in the west wing, Miriam Grover, class of 1914, was awakened by a strange crackling sound and an eerie orange light through the transom above her door. As Grover got out of bed, her roommate, Jinny Moffat, told her to go to Olive Davis 1886, the director of halls and residence. … Miss Davis instructed Grover to alert Edith Tufts 1884, the registrar, on the floor below. By the time Grover spoke to Miss Tufts, the Japanese gong had been sounded, and students were beginning to congregate at their assigned spots….

Because the student fire chief in 1913 had insisted on unannounced nighttime fire drills in each dorm (against the advice of the College physician), many students assumed the gong and the subsequent electric corridor bells were signaling another drill and went about their usual routine of closing their windows, turning on the lights in their room, throwing on a robe or kimono and slippers, and heading down to their assigned meeting spot in the Centre.

(From “Up in Flames” by Lisa Scanlon Mogolov ’99 in a special issue of Wellesley magazine, The Night That Changed Wellesley.)

By all eye-witness accounts, calm and discipline ruled the day, with no “outcry, lamentation, or questioning” slowing down the process of getting everyone out safely. Which they did. Stunningly, no human lives were lost. The April 2, 1914, issue of the Wellesley College News—digitized and readable online now—had extensive coverage of the fire. Wellesley student Barbara Bach Phipps 1916 compiled a photograph album documenting the destruction by fire of College Hall, which is also in a digitized form in the College Archives.

In the aftermath of that morning 100 years ago, Wellesley would be forever changed, both by the buildings that replaced College Hall—seven in all, the last of them opening in 1931—and by the response of Wellesley’s graduates and faculty members. "This fire fused the alumnae body together," says Andrew Shennan, provost and dean of the college, who adds that much of what the college has succeeded in becoming can be traced to the fire.

(From "Remembering the Fire of 1914" by Lawrence Biemiller in the March 10 Chronicle of Higher Education.)

Looking Back

At the one hundredth anniversary of this dramatic and course-changing night, Wellesley honored the heroism and grit of the women who survived the fire, saving each other and many assets from the burning building. We continue to be grateful to and take inspiration from their resumption of the spring academic term only three weeks later. The success of the rebuilding effort wasn't always a foregone conclusion.

After the flames destroyed College Hall, the heart and anchor of the campus, college leaders faced a crucial decision: Should they cut their losses and shut down the school, or attempt to raise more than $2 million—the equivalent of about $47 million today, according to one Wellesley economist—in just months to keep the campus going?

(From "Wellesley College Remembers Trial by Fire" by Jaclyn Reiss in the March 16, 2014, Boston Globe.)

We know the answer to that question now, of course, and its lasting effects. The adaptability and resilience, resourceful fundraising, and longer term thinking by undergraduates, alumnae, faculty, and College leadership, supported by the generosity of other institutions and philanthropists, made Wellesley what it is today.

Centennial Commemoration

Although no one was hurt, and many objects were saved by students and faculty as the fire burned, much was lost on March 17, 1914, and College Hall was left in ruins. Students, faculty, and staff gathered in the Houghton Memorial Chapel that morning, and then the students were sent home for three weeks while the College began the process of recovering from the devastation.

On March 17, 2014, Wellesley College remembered this pivotal event in its history. Special commemorative events for the entire community included a morning meeting in the chapel as happened 100 years previously. This time, however, breakfast was served; music was sung by the Tupelos; students, faculty, staff, and guests read personal letters written in the days and weeks after the fire by members of the community; and President Bottomly, dressed as Ellen Fitz Pendleton might have been in 1914, addressed the gathering. In the afternoon, a special exhibition in the Davis Museum of artifacts saved from the building and lasting these many decades, was opened with remarks by historian and Provost of the College Andy Shennan.