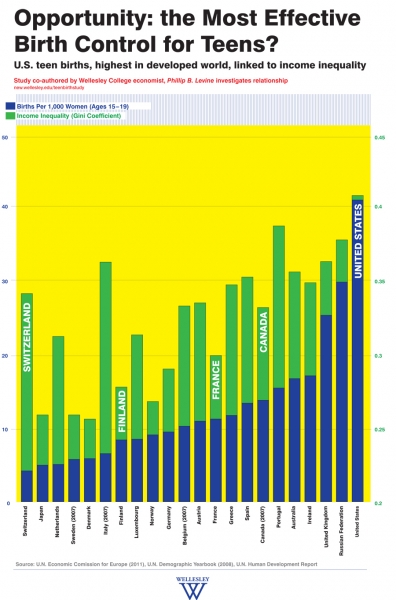

U.S. teen births highest in the developed world; Wellesley economist investigates relationship to income inequality

Studies find:

- Low-income teens living in areas of high inequality are more likely to have a baby rather than invest in their own economic progress

- Recent downward trend in U.S. teen birth rate largely unrelated to abstinence only, contraceptive access, or mandatory sex education

WELLESLEY, Mass.—New research reveals the surprising economics behind the U.S. teen birth rate, still the highest in the developed world: high income inequality and low opportunity cost. American teens are two and a half times as likely to give birth as compared to teens in Canada, around four times as likely as teens in Germany or Norway, and almost ten times as likely as teens in Switzerland. The study, “Why is the U.S. Teen Birth Rate So High,” will be published in the 100th issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, May 22, 2012.*

For the first time, Wellesley College economist Phillip B. Levine and University of Maryland economist Melissa Schettini Kearney conducted a large-scale empirical investigation to study the role that income inequality plays in determining early, non-marital childbearing. Using econometric analysis of large-scale data sets, Levine and Kearney discovered that variation in inequality across the United States and other developed countries can account for a sizable share of the stunning geographic variation in teen childbearing. They found that poor teens were more likely to give birth if they lived in a state with high income inequality. Moving from a low inequality state to a high inequality state increased their rate of teen childbearing by 5 percentage points.

For the first time, Wellesley College economist Phillip B. Levine and University of Maryland economist Melissa Schettini Kearney conducted a large-scale empirical investigation to study the role that income inequality plays in determining early, non-marital childbearing. Using econometric analysis of large-scale data sets, Levine and Kearney discovered that variation in inequality across the United States and other developed countries can account for a sizable share of the stunning geographic variation in teen childbearing. They found that poor teens were more likely to give birth if they lived in a state with high income inequality. Moving from a low inequality state to a high inequality state increased their rate of teen childbearing by 5 percentage points.

According to Levine, who teaches economic analyses of social policies as Katherine Coman and A. Barton Hepburn Professor of Economics at Wellesley College, it’s long been argued that a sense of hopelessness and despair is closely related to higher rates of teen pregnancy. Levine explained, “If a young woman sees little chance of improving her life by investing in her education and career skills, or by marriage, she is more likely to choose the security, immediate gratification and happiness of parenthood. Our work captures this idea in a standard economics model of decision-making.”

Levine and Kearney derive a formal economic model that incorporates the perception of economic success as a key factor driving one’s decision to have an early, non-marital birth. Their findings show that for poor women living in locations of high inequality, such as the United States, limited opportunities for advancement reduce the opportunity cost of early, non-marital childbearing—and thereby increases its occurrence.

Related study investigates factors behind downward trend

While the U.S. teen birth is the highest in the developed world (more than triple the rates in Spain, Japan, and Sweden), according to the CDC’s April 2012 report, the national rate has declined since its 1991 peak. In a related study, Levine and Kearney investigated possible factors behind this trend. The data showed that expanded access to family services through Medicaid and reduced welfare benefits had statistically relevant impact on the lowered rates. However, these factors accounted for only 12% of the teen birth rate decline. Increased contraceptive use and reduction in sexual activity contributed roughly equally. Furthermore, Levine and Kearney found that abstinence only or mandatory sex education had no impact on teen birth rates. The researchers determined that factors typically claimed to impact teen pregnancy actually explain very little of the recent trend and call for further investigation of economic factors.

Implications for Policymakers

Levine and Kearney conclude that teen childbearing is so high in the U.S. because of underlying social and economic problems. In other words, teenage childbearing is a symptom, not a cause of poverty.

The findings bear important implications for U.S. policymakers. According to Levine, who has closely studied the economics of social policies, the high rate of teen childbearing in the United States matters because it is a marker of a social problem, rather than the social problem itself. “If the problem is perceived lack of economic opportunity, then policy interventions need to attack that. Access to early childhood education programs and college financial aid, for instance, have proven to be successful in improving the earnings—and sense of hope—of participants. Our findings show that these programs may also have the added benefit of lowering teen pregnancy rates. Giving teens a sense of opportunity and hope may be a much more powerful prescription than abstinence-only, sex education, or birth control combined.”

“Why is the Teen Birth Rate in the United States so High and Why Does it Matter?" will be published May 22 in the Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol. 26, No. 2 (Spring 2012). pp.141-166. *Advanced online access available to journalists:

More research on teen births, co-authored by Phillip B. Levine and Melissa Schettini Kearney, is published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and available online:

“Explaining Recent Trends in the U.S. Teen Birth Rate” http://www.nber.org/papers/w17964

“Income Inequality and Early Non-Marital Childbearing: An Economic Exploration of the "Culture of Despair" http://www.nber.org/papers/w17157

About Phillip B. Levine, Katharine Coman and A. Barton Hepburn Professor of Economics

About Wellesley College

Since 1875, Wellesley College has been a leader in providing an excellent liberal arts education for women who will make a difference in the world. Its 500-acre campus near Boston is home to 2,400 undergraduate students from 50 states and more than 75 countries.

Press Contacts (interviews and images available)

Sofiya Cabalquinto, Wellesley College, 781-283-3321, scabalqu@wellesley.edu

Anne Yu, Wellesley College, 781-283-3201, ayu@wellesley.edu