Is Cancel Culture Toxic? Professor Erich Hatala Matthes Joins the Debate

Is cancel culture toxic? Is it real? What exactly is it, anyway? On November 9, Erich Hatala Matthes, associate professor of philosophy at Wellesley, participated in a debate called Cancel Culture Is Toxic. The title alone made quite a stir: Responses to the tweet announcing the event fell immediately on either extreme: “Is there any doubt about it?” and “Cancel culture is free market.”

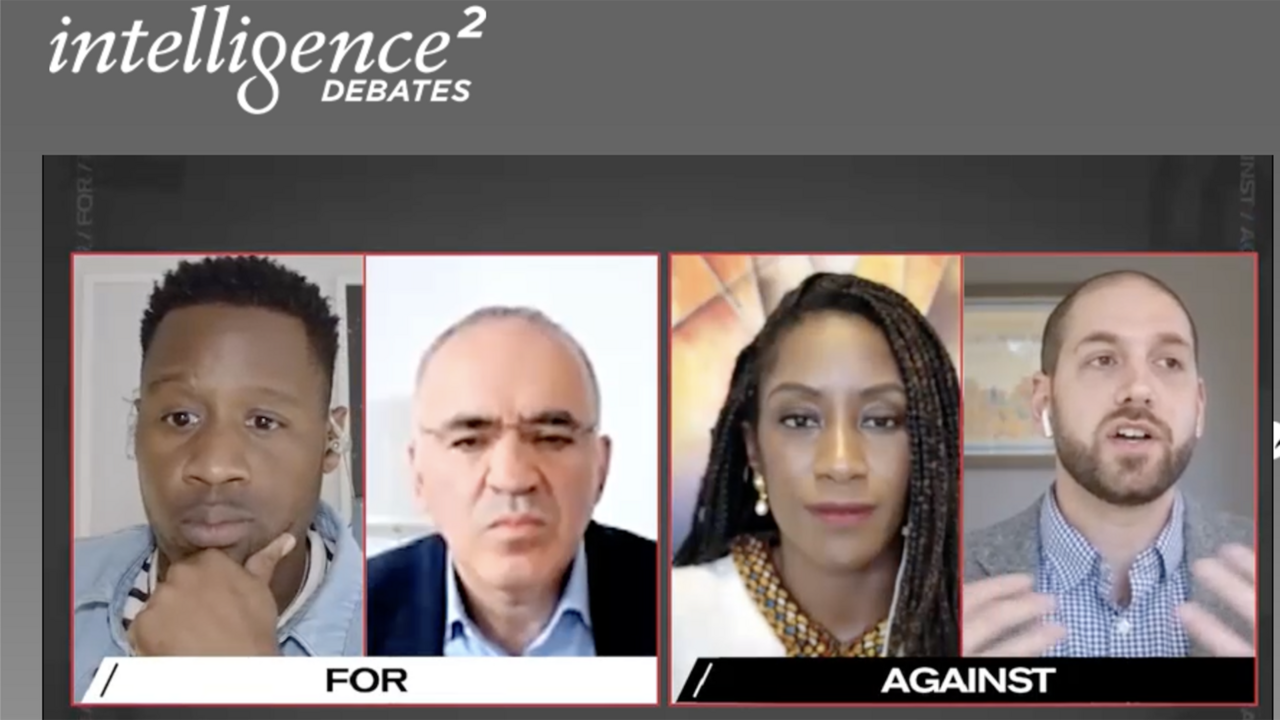

Intelligence Squared U.S., an organization that seeks to “restore critical thinking, facts, reason, and civility to American public discourse,” sponsored the debate, which was held via Zoom. The organizers reached out to Matthes to ask if he would participate by arguing against the motion that cancel culture is toxic alongside Washington Post columnist Karen Attiah, who has won several awards for her work seeking accountability for the murder of her colleague Jamal Khashoggi. Arguing for the motion were Kmele Foster, a media entrepreneur and political commentator, and Garry Kasparov, chairman of the Human Rights Foundation and the Renew Democracy Initiative. John Donvan moderated the debate, which followed a strict Oxford style, with the participants alternating in presenting their points and engaging in a heated debate only at the very end.

In a political culture where we have normalized expressions of prejudice and bigotry, public shaming is a perfectly legitimate means of social resistance against those expressions.

Erich Hatala Matthes, associate professor of philosophy

Foster and Kasparov argued that cancel culture is a “frightening and widespread” phenomenon that makes people who hold certain views afraid to speak out, which stifles dialogue and discourse. Matthes and Attiah countered that cancel culture, at least in the way the media and the conversative right paints it, does not really exist. People are not losing their jobs or being silenced at the rate that critics of cancel culture want us to believe, and, actually, more voices than ever are being heard now thanks to the calling out and questioning of dominant voices.

“In a political culture where we have normalized expressions of prejudice and bigotry, public shaming is a perfectly legitimate means of social resistance against those expressions,” said Matthes. He pointed out that when people get “canceled” they tend to go on to get an even larger platform and more opportunities to speak out. Matthes also noted that, conveniently, critics of cancel culture often don’t mention the occasions when left-leaning activists and speakers get “canceled,” such as when Nikole Hannah-Jones, creator of the 1619 Project, was uninvited to speak at the Middlesex School, or Colin Kaepernick was punished by the NFL for his activism. Matthes concluded by saying that he believes the resolution itself is toxic and that the whole debate around cancel culture focuses on the wrong thing: We should be talking more about what is getting people called out in the first place, rather than debating whether they were actually “canceled.”

“The debate was an unusual experience for me,” Matthes said after the event, in an email. “While it is fundamental to the nature of philosophy to consider arguments, objections, and replies, in the classroom I always try to cultivate an environment where we’re engaged in a shared search for truth: While we consider many different perspectives, we’re on the same team trying to sort through them and see which arguments hold water. I don’t love the way that the Oxford debate style inherently sets up the participants as being on ‘different sides.’” Despite his reservations about the structure of the conversation, Matthes was glad to have the opportunity to comment on his issues with the motion and to dissect the framing of the debate itself.

Matthes said his views of cancel culture, especially in the arts, are much more nuanced than he was able to get across during the debate. He is the author of the forthcoming Drawing the Line: What to Do with the Work of Immoral Artists from Museums to the Movies, a book intended for a general audience. (“No prior philosophy experience required!” assured Matthes.) It is for anyone who still loves a movie produced by Harvey Weinstein, say, but also feels a little icky about that now.

“In my book, I argue that arts institutions could use substantial reform with respect to weeding out predators, for instance,” explained Matthes. “But I also argue that individual art consumers deserve a lot of moral latitude when it comes to the art that they engage with, which has both moral and aesthetic importance. So even when it comes to artists such as R. Kelly or Woody Allen, I don't necessarily think that the best response to their immoral actions requires cutting their art out of your life. It does matter, though, how we engage with that art.”

Part of engagement is conversation, and even if the Oxford style wasn’t the most natural or fluid format for it, that is what the Intelligence Squared debate provided.

“My team’s side in the debate required that we defend ‘cancel culture,’ so the deck was sort of stacked against us given that cancel culture has a pejorative connotation and is an ambiguous phenomenon,” said Matthes. “I have no interest in defending harassment, for instance, which some people might lump in with cancel culture. But I do believe, as we argued, that the panic about cancel culture generally functions as a cover for avoiding criticism, and I’m glad we had the opportunity to make that argument.”