How Wellesley Is Rethinking Its Curriculum to Support First-Gen Students

Kim Hernández ’21 was pretty rebellious growing up. “I talked too much,” she said. “I would get bored easily with the class and cause distractions.” At her charter school in her hometown of Houston, Texas, she was often in trouble and felt her teachers viewed her as unlikely to be successful.

In her sophomore year, Hernández opted to try the local public school. There, she saw students who lacked ambition—something she wanted to avoid—but she also met a freshman who was planning to apply to college, and who inspired her to do the same.

She had never considered the possibility before then. “My mom never said ‘Go to college.’ I know a lot of parents didn’t do that,” she said. “My mom never did.”

Hernández, who liked math and did well enough to place into calculus, decided to return to the charter school and focus on her education.

In Texas, students in the top 10 percent of their graduating class receive automatic admission to the state’s public universities. Hernández worked hard to break into that 10 percent; when she didn’t, she shared her immense disappointment with her mentor, and they discussed the obstacles she faced outside of school. The mentor nominated Hernández for a Posse scholarship, which she received and which led her to Wellesley—the first member of her family to attend college.

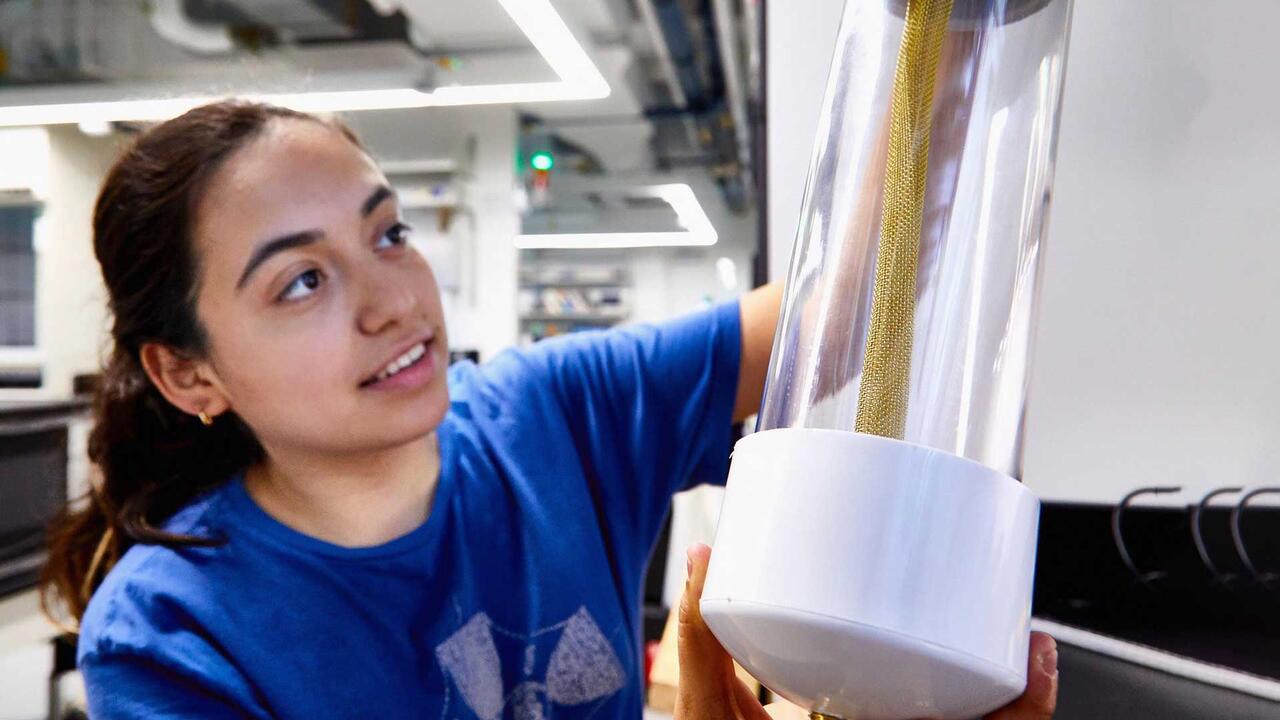

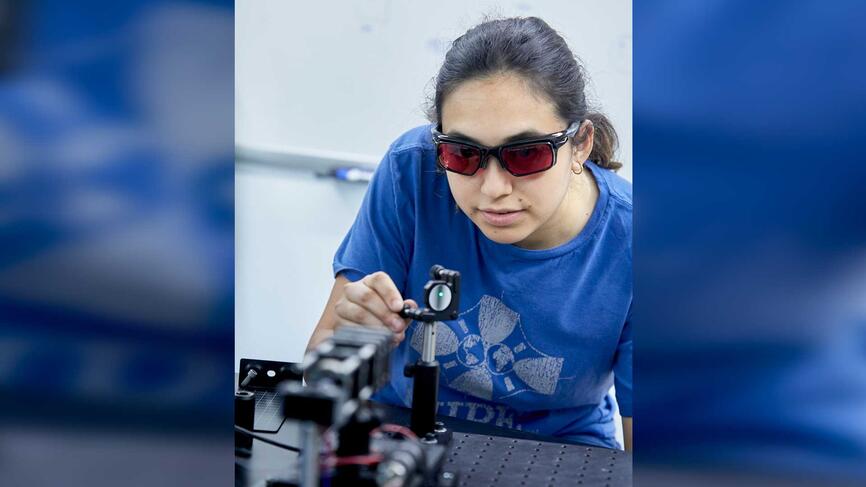

At Wellesley, Hernandez found herself in a situation familiar to many first-generation college students. She planned to major in applied physics with a math minor, but felt she wasn’t as prepared as others in her first-year physics class because her high school hadn’t offered AP physics. “That’s where I realized, wait, these people come from really good schools,” she said. “Their parents are educated. These people know what they’re doing.” She said the realization was “a little rough.”

Wellesley faculty recognize that many of the College’s high-achieving first-generation students haven’t benefited from the type of academic, economic, and familial support other students have had, and that this difference may affect their college experience. To address that disparity, they are rethinking the accessibility of their courses and finding ways to create environments that support students from a wide variety of backgrounds.

Rebecca Garcia, director of Wellesley Plus and Wellesley First, said it has been refreshing to see faculty members ask themselves some important questions: Who does and doesn’t benefit from my curriculum and teaching style? What values am I promoting in this classroom? How can I ensure all students feel they belong and are learning? “By prioritizing and validating the first-generation college experience, some departments have been able to shift their culture, bringing about greater community, self-efficacy, and belonging for all students,” she said.

Wellesley’s physics department, for example, conducted a self-study in 2015 to determine strengths and weaknesses in its program. Yue Hu, professor of physics and chair of the physics department, said the results showed that “we needed to rethink our curriculum content, how we taught it, and how we could build a more vibrant, inclusive community that could provide the best possible learning experience for our students with diverse backgrounds and career interests.”

Working closely with the Wellesley chapter of the Society of Physics Students (SPS), the physics faculty revised its curriculum in 2018. James Battat, associate professor of physics, said the goals were to provide a better entry point to the major; use a collaborative learning/studio model for in-person instruction; offer more choices at the 300 level; and help students gain stronger senses of identity as scientists through peer instruction. “We expect that these changes will benefit all of our students,” he said. “But physics education research tells us that the changes…have even more significant positive impacts on first-gen students and students of color.”

As recently as 2014, the department counted majors in single digits. In the first year after the curriculum changes were implemented, the number jumped to 28, and just under half are first-generation and underrepresented students. (Hu noted that the “tireless work with the students” of Katie Hall, distinguished senior lecturer in physics, contributed tremendously to the success of the department’s curriculum change.)

Becky Belisle, assistant professor of physics, helped create the physics learning assistant (LA) program. LAs are students who have already taken a particular course and are present during class time to work directly with students who are currently enrolled in it. The program helps students learn and fosters a stronger sense of belonging in the physics community, Battat said. Students and LAs build relationships across class years, and diversity within the LA group ensures that students can interact with mentors of similar backgrounds. LAs also bring a valuable student perspective to the teaching team.

The faculty in the Writing Program hope to encourage upperclass students to act as mentors as well, particularly for first-years. “We think such mentors can complement the work that’s done by the writing tutors to support first-gen, first-year students; and we also see this as a way to offer upperclass students an opportunity to serve in a leadership role,” said Jeannine Johnson, senior lecturer in the program.

“By prioritizing and validating the first-generation college experience, some departments have been able to shift their culture, bringing about greater community, self-efficacy, and belonging for all students.”

Rebecca Garcia, director of Wellesley Plus and Wellesley First

The program offers several first-year writing courses to help students transition from high school to college writing. Some sections are reserved for first-gen students, on topics faculty think might resonate with them—courses like Writing for Change: Protest Literature in America, taught by lecturer Erin Battat; Are We What We Eat? Writing About Food and Culture, taught by lecturer Anne Brubaker; and Wellesley and the World, taught by Johnson.

“These classes also offer students a supportive space in which to develop their writing skills, their confidence as scholars, and their sense of belonging to the larger Wellesley community,” Johnson said.

Mirka Estrada ’23 found that to be true. Estrada is part of WellesleyPlus—a program that helps students, particularly first-gen, transition into college. She took one of the writing classes designed for students in that program, on literature and scholarship about race and immigration—topics she felt had been missing from her previous educational experience. “Seeing yourself in literature and seeing different scholars that look like you just really made the environment feel more homey,” she said. It also helped her manage in other classes where there was less student diversity. Being in classes surrounded by people who didn’t share her experience didn’t intimidate her, she said, “because I was validated in this one space…it just really helped propel that confidence I had into other areas that first semester.”

Confidence is what Etsegenet Tsega ’22 encourages first-gen students to bring with them to Wellesley. “Never feel intimidated or shy to share your thoughts and ask questions. Always remember there are people in Wellesley who love you and are by your side,” she said. Tsega is an economics major but has taken a number of philosophy courses. When asked what drew her to philosophy, she quoted Corinne Gartner, associate professor of philosophy: “Philosophy teaches you how to think.”

The philosophy department, too, has been increasingly concerned with issues of equity and access, and the faculty frequently discuss how to achieve inclusive pedagogy. “I think all of us are just trying to make sure that access to opportunity is as wide as it can be,” said Catherine Wearing, associate professor of philosophy.

Implementing the Home Base Mentoring Program, conceived by Julie Walsh, assistant professor of philosophy, is one way the department is pursuing that goal. Every student enrolled in a philosophy course must meet at least once with a student writing tutor; making this a requirement destigmatizes asking for help. “That’s sometimes a barrier to first-gen or under-resourced students,” Wearing said, “that sometimes they aren’t as practiced at going out and asking what’s available to them.” The department is also mindful of hiring diverse tutors—including ones who are first-gen—so that students can see a wide range of peers who excel in philosophy.

Tsega said the philosophy department makes her feel as though she is surrounded by people who want her to succeed. “It is a department that seeks ways to make first-gens’ Wellesley experience meaningful and impactful,” she said.