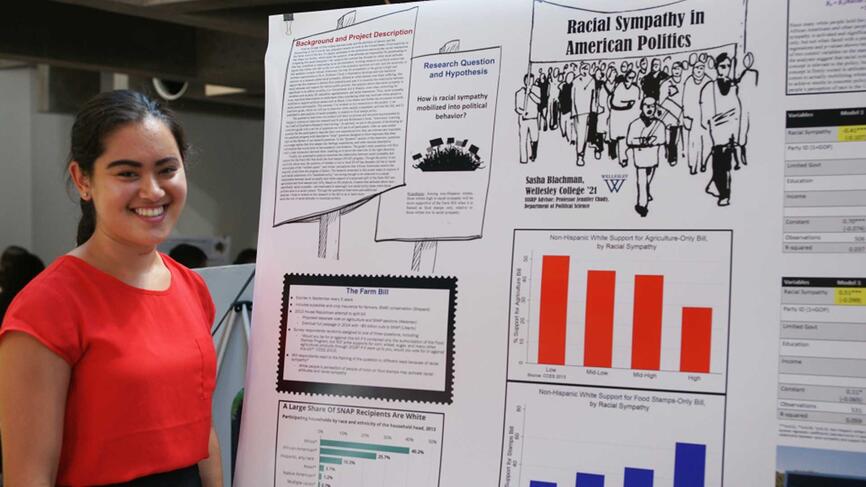

Student and Professor Connect Through Research into Politics and Race

Jennifer Chudy, Knafel Assistant Professor of Social Sciences and assistant professor of political science, and Sasha Blachman ’21 both started at Wellesley in 2017. When Blachman learned about Chudy’s research into politics and racial sympathy, she quickly recognized how her own interests in race and politics intersected with Chudy’s work. “From the beginning of my freshman year I knew I really wanted to take a class with her,” Blachman said. “I have been certain about my political science path since the start of college, and she stood out to me as a great mentor.”

Blachman, a political science major, took Chudy’s Research Methods in Political Science class in the spring of her first year—she rearranged her entire schedule to fit it in. Chudy remembers meeting her in this course. “She was one of the only first-year students enrolled, and I was immediately impressed by her deep commitment to the demanding material,” Chudy said. “However, she really distinguished herself one afternoon in office hours when she showed me a spreadsheet she had been working on in her free time. She was analyzing data related to gerrymandering and had many questions on how to source and organize the data and what it all meant. I was struck by this display of deep intellectual curiosity.”

Blachman started working with Chudy that summer and will continue during her senior year. This summer, Blachman received funding from the Social Science Summer Research Program through the Knapp Social Science Center to work with Chudy on a project titled “Racial Sympathy in American Politics,” studying “white racial attitudes that may contribute to eradicating racial discrimination,” according to Blachman’s abstract. Chudy, who has been a trailblazer in this area of research, defines racial sympathy as “white distress over Black suffering.”

Blachman spent the summer analyzing transcripts from interviews she and Chudy conducted with white anti-racist activists during the 2019–20 academic year. “It was a really surprising concept to me to be studying racial justice by interviewing white Americans,” said Blachman. “As someone who is mixed race, I’ve struggled to find my place in the racial justice movement. I’ve faced microaggressions, but I’ve also benefited from being half-white. For a long time, I didn’t realize that being an ally is so much more than simply not being a white racist—that inaction is complicit in injustice. Martin Luther King once identified ‘the white moderate’ as the critical impediment to racial progress. And that’s exactly why Professor Chudy’s prescient efforts to study racial sympathy are so important: Her work can help explain and facilitate the transformation of white bystanders into activists and agents for change.”

They were finishing their interviews with the activists in early June, around the time protests against police brutality were spreading across the country in response to the killing of George Floyd in Minnesota. They opted to stop interviewing at that point—there would be no way to accurately compare the interviews conducted before the protests with ones after because of the huge shift in national consciousness and the perception of anti-racist activism, according to Blachman.

Blachman wrote in her abstract that her analysis of the interview transcripts “suggests these activists share a dissatisfaction with the Democratic Party’s handling of racial issues and disillusionment with standard political avenues for progress. If these attitudes are widespread, especially among white Americans newly mobilized in the wake of the George Floyd protests, liberal politicians may need to reevaluate the hope that the momentum of today’s racial justice movement will translate directly from strength in the streets to results in the voting booth.” She noted that this is an area to keep an eye on as she continues her research.

“I am so proud of all the work she has done and hope that the project has shown her the rewards and challenges of conducting social science research.”

Jennifer Chudy, Knafel Assistant Professor of Social Sciences and assistant professor of political science

Blachman said she was surprised that the project taught her not just about political opinions, but also about interdependence in the political process. “In my intellectual view, this activism, it’s so, so important—the outpouring on the streets, the social media, the accountability of elected officials, because they’re getting people calling in or emailing in about Breonna Taylor and that kind of thing is so important,” she said. “But it also needs to be translated to the ballot box, and it needs to be translated into voting and be harnessed for political change. I’ve never seen myself as a protestor or an academic. But doing this research and listening to the personal stories of these activists has shown me that we can all learn and inspire each other.”

Blachman said interviewing the research participants was her favorite part of the project. “We were fortunate that these people were really open with us about their personal experiences and their political beliefs,” she said. “It was really valuable for me to get to hear from different people of different backgrounds…to hear from people from the South, some of whom grew up during segregation, while Jim Crow laws were still in place…that really humanized history, and I felt more grounded in the work I was doing.”

The next steps in the project include collecting more data by sending out a nationwide survey. “The hard thing about surveys is that you can’t tell causality. If we see a huge spike in racial sympathy, we can’t say ‘this was directly because of the George Floyd protests,’ but I think it’ll provide really great insight into the mood of the country,” Blachman said. “And, like most surveys, it will lead to more questions than answers.”

Chudy has enjoyed watching Blachman grow from a research assistant to a collaborator. “I am so proud of all the work she has done and hope that the project has shown her the rewards and challenges of conducting social science research,” she said.

Blachman said she values the close relationships she’s had with her professors at Wellesley. She has taken a number of classes with Chudy and with Stacie Goddard, Mildred Lane Kemper Professor of Political Science and faculty director of the Madeleine Korbel Albright Institute for Global Affairs. She says getting to know professors as scholars and as people improves her classroom experience. “They make me excited to be there,” she said. “I was 9 years old when my dad told me a brilliant woman named Hillary Rodham Clinton [’69] was running for president. That was the day I decided to try to follow her footsteps into public service and be an advocate for women. My Wellesley professors inspire me daily to keep learning and asking tough questions as I chase that dream.”