A Solitude of Space: Studying Emily Dickinson in the Time of COVID-19

Back in November, long before our world was overturned, I sent an email to Dan Chiasson, Lorraine C. Wang Professor of English at Wellesley. The subject line read: “I’m Nobody.”

I was writing to ask if I could audit ENG 357: The World of Emily Dickinson in the spring. I admit it felt a bit audacious to refer to one of Dickinson’s most famous poems.

I’m nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there’s a pair of us—don’t tell!

They’d banish us, you know.

How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!

But Chiasson replied, “Catherine, with that subject line, how can I say no??”

“I’m Nobody!” is the first poem I remember knowing. Perhaps it actually was the first; perhaps I learned it later, and it effaced other, simpler rhymes. It hardly matters. Because what I remember, what I still embrace as “first poem,” is this Emily Dickinson verse, written in Amherst, Mass., circa 1861, and listed as #288 in the Thomas H. Johnson edition of her poems, published initially in 1960.

So in January, I bought a fresh copy of Johnson’s 770-page The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson and slipped diffidently into my first college-level English class since the 1970s. Room 338, on the third floor of Green Hall, was chilly that day. Every seat was filled, and we sat elbow-to-elbow and notebook-to-notebook as class began.

Reading my notes from those first weeks, I see that our class explored Dickinson family biography, read excerpts from essays about 19th-century material culture and attitudes to death, about the intellectual life of Amherst, Mass., and about the role of the Civil War in Dickinson’s work. We went online to interpret her handwriting and her use of punctuation—those dashes!—amid the riches of the Emily Dickinson Archive, an open-source website of the poet’s handwritten manuscripts. We speculated about the unsolved mystery of her withdrawal from the world into her bedroom on the second floor of the Dickinson homestead. We began to call her Emily, addressing her as one might a friend rather than with the traditional English-major trope of “the speaker,” or “the narrator.”

And in every single class, we worked as a group—auditors included—reading the poems aloud, dissecting their diction and dashes, their moments of violence, their verbal puzzles, their humor, and their reverence for nature. Together, we were discovering what Chiasson calls “one of the most thrilling and idiosyncratic minds in literature.”

This was heady stuff for me; I could feel long-closed doors in my mind and imagination creaking open. I loved being around the energy and commitment of the students, their willingness to risk their own interpretations of Emily’s work and life. I loved Chiasson’s quirky erudition, his references ranging from the metaphysical poets to pop culture and TV, sometimes in a single sentence.

There was a Tuesday in early March warm enough to allow us to hold class outside, declaiming Dickinson in the amphitheater behind Alumnae Hall. We were looking forward to an April field trip to the Emily Dickinson Museum in Amherst; to a 5 a.m. silent meeting in May on the shores of Lake Waban to listen to the birds’ dawn chorus; to a final gathering at our professor’s house to watch episodes of the cult favorite streaming TV show Dickinson.

But everything changed. In mid-March, we left Wellesley’s campus, and as Emily wrote in #303, “then shut the door.”

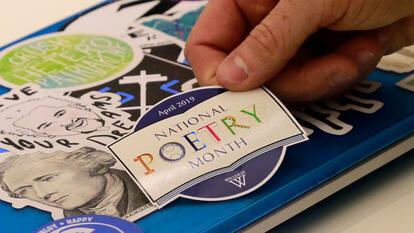

This is an excerpt from an article by Catherine O’Neill Grace that appears in the summer 2020 issue of “Wellesley” magazine. Read the full story on the “Wellesley” magazine website.