As Research Labs Reopen, Faculty Share Shutdown Challenges and Hopes

When Wellesley’s campus closed in mid-March, Yui Suzuki, associate professor of biological sciences at Wellesley, packed up his flour beetle and moth colonies and brought them home to his one-bedroom apartment in Natick.

“The beetles were relatively easy to maintain because they were very small and didn’t need much space,” he said. “The only issue was finding food for them: These beetles live on organic whole wheat flour, but stores were completely out of stock.”

The moths, he said, were more problematic as they are three inches long and need space to mate. “I have been evolving three strains of moths for over three years now, so I had to make sure to keep them alive,” Suzuki said. He researches genetic accommodation, a process by which an environmentally induced change in development drives the process of evolution, rather than a mutation that generates a new phenotype or trait. “The room became quite dusty when the adults started mating, but they seemed to like my living room more than the lab because they laid more eggs than usual,” he said. “My wife was very patient in letting us co-exist!”

Over the past few weeks, Wellesley College’s Science Center has begun to reopen as part of Phase 1 of Massachusetts’ plan, which allows labs in institutions of higher education to resume work. Suzuki has moved his beetles and moths back to the lab, a better environment as mold could potentially become an issue now that temperatures are rising.

As Wellesley shifted to remote instruction, much of the science research at the College was paused. At the height of the coronavirus surge in Massachusetts, a skeleton staff at the Science Center, led by Megan Núñez, Nan Walsh Schow ’54 and Howard B. Schow Professor in the Physical and Natural Sciences, professor of chemistry, and dean of faculty affairs, and Cathy Summa ’83, associate provost and director of the Science Center, helped keep faculty research viable and maintained instruments so that they would be running smoothly when research restarted and faculty could return. They also helped prepare returning Science Center staff and faculty for the new health and safety protocols in effect on campus.

Back in mid-March, Louise Darling, Knafel Assistant Professor of Natural Sciences and assistant professor of biological sciences, had to power down her cell cultures, putting them in a -80 Celsius freezer or in liquid nitrogen for long-term storage. These cell cultures are essential to her lab’s work studying the interaction of antimicrobial peptides with the membranes of bacterial cells in the hope of improving their designs as an alternative to conventional antibiotics, research Darling is also collaborating on with chemistry professor Donald Elmore.

“They are the living model system where we test our hypotheses. Almost every assay performed in my lab uses these cells,” Darling said. “Cell culture allows for our reductionist approach to asking mechanistic questions. They give us a much more controlled system/environment than an intact organism, allowing us to ask more focused questions that are also more tractable to experiments performed by undergraduate researchers.”

Thanks to ongoing help from her lab’s current post-baccalaureate research assistant, Mayla Thompson, Darling has gotten her cultures going again, and she said they are “happily” growing at a rate that will allow experiments to resume again soon.

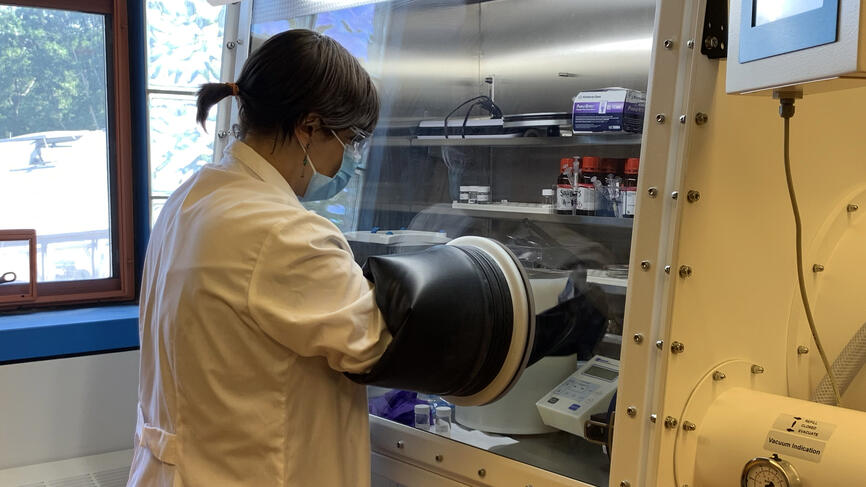

Rebecca Belisle, assistant professor of physics, and the students in her lab had to keep the semiconductors and solar cells she fabricates and uses in their “glovebox,” making sure they had a continuous supply of nitrogen and remained in operation. Summa’s staff were instrumental in coordinating this.

“My glovebox is kind of the heart of my lab. It’s the first thing I bought when I began to build my lab at Wellesley two years ago, and when we turned it on for the first time it felt like the official start of my research program,” Belisle said. “Our materials react with water and oxygen in the environment, and the glovebox is a piece of equipment that maintains a dry nitrogen atmosphere for us to safely work in. If the glovebox turns off or loses pressure, ambient air can get in, compromising our materials and our experiments.”

“Students are absolutely the lifeblood of research . . . Interruptions like this not only affect current progress, but they disrupt the continuity of training overlapping students that can work together and train one another.”

Mathew Tantama, assistant professor of chemistry

Science faculty have had different experiences during this time away, and during the gradual return to campus. Mala Radhakrishnan, associate professor of chemistry, who uses computational methods to better understand molecular recognition in complex, dynamic biological environments, or how molecules interact and physically bind with each other in such environments, was able to continue the computational aspects of her research remotely, but some experimental work she is doing in collaboration with Elmore is still on hold.

Mathew Tantama, assistant professor of chemistry, is new to the College, and the pandemic has delayed the start of work in his lab. “I may be in a different position than other new faculty given that I am moving my lab from Purdue University,” he said. “I actually started to set up my lab when I first arrived last August, and I was approximately 75 percent set up when we went remote. This entailed shipping my equipment, supplies, and reagents from Purdue to Wellesley, which is not yet complete because of the shutdown. For a biochemist like myself, I have quite a bit of scientific equipment that is specific to my research program, and because my work involves live cells, I also use quite a bit of consumable supplies, chemical and biological reagents, and actual live cells that require cryogenic storage.”

The pandemic has had a huge impact on recruiting students to labs like Tantama’s, and he speculated that this might have the deepest and longest-term repercussions on his research program. “Students are absolutely the lifeblood of research, and typically I would have been recruiting and training current and new students—from all backgrounds of science and non-science, not just biochemists—over the summer,” he said. “Interruptions like this not only affect current progress, but they disrupt the continuity of training overlapping students that can work together and train one another.”

The science faculty said they are grateful to the Science Center leadership and staff who kept things running during the shutdown and have been integral in the reopening, but they miss and look forward to the interactivity of research and in-person collaboration with their colleagues and students.

“Opening the doors to the Science Center again doesn't mean that business as usual will resume for many faculty,” said John Goss, assistant professor of biological sciences. Goss’ lab shut down completely amid the pandemic, because of the uncertainty of when they could return. For three months, they could not collect new data, but now they are getting things up and running again. Goss researches the conserved regulatory mechanisms of cell division in yeast, and he’s had to work odd hours recently: He is often in the lab from 8 pm until midnight, after a day of remote work and after his young children are asleep.

“I've been the only person on our floor working during these late hours, so although I am able to get work done, the atmosphere isn't the same,” he said. “I miss the camaraderie of having my students in our lab and my colleagues working in the neighboring labs. People sometimes imagine researchers being all alone in their labs as a matter of course, but in reality, it is very interactive and social—you are constantly bouncing ideas off colleagues or just chatting throughout the day.”