MeToo Lit: Reading the Silence Breakers

In October 2017, the hashtag #MeToo was shared 12 million times in 24 hours across social media, bringing a new level of visibility to the pervasive problem of sexual violence and to the #MeToo movement itself, founded by activist Tarana Burke a decade before. For the past two years, untold stories from the past have been given a hearing in a new genre, MeToo Lit, helping to answer the question, why now?

Leigh Gilmore, distinguished visiting professor of women’s and gender studies at Wellesley, recently published an essay exploring the impact of these emerging stories. She has compiled the following reading list, which represents a sampling from this burgeoning feminist genre that will enable interested readers to fill out the before and after of #MeToo, and shine some light on how the movement might continue to evolve.

Content Warning: These books discuss sexual assault in graphic terms.

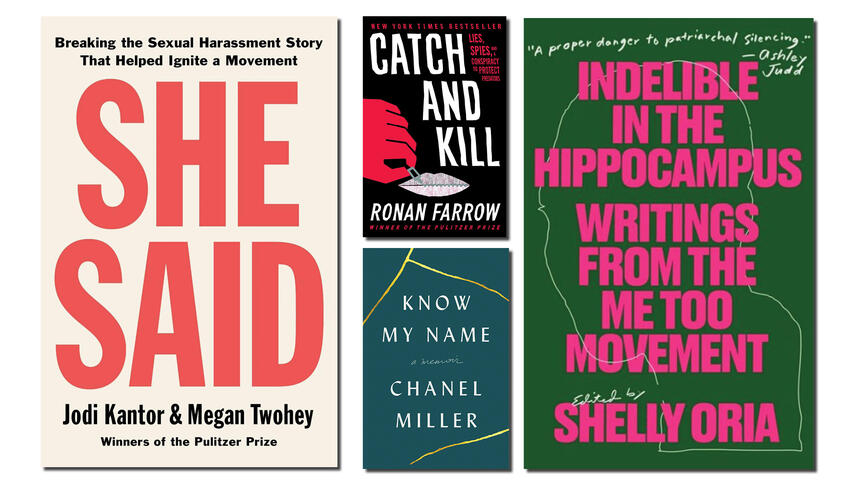

She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement, Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey

Reporters Jodi Kantor and Meghan Twohey broke the Harvey Weinstein story in the New York Times. She Said focuses on the daily process of reporting this explosive story, and the result is a riveting page-turner. Kantor and Twohey hit plenty of obstacles—including reluctant survivors, Weinstein enablers, duplicitous lawyers, and Weinstein himself—but ultimately convince enough women to go on the record to overwhelm he said/she said with a resounding chorus of SHE SAID. She Said documents how Kantor and Twohey ungagged the women, transforming them through the reporting process into silence breakers.

Catch and Kill: Lies, Spies, and a Conspiracy to Protect Predators, Ronan Farrow

Together with Jodi Kantor and Meghan Twohey of the New York Times, Ronan Farrow was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for public service in 2018 for his reporting on Harvey Weinstein in the New Yorker. Catch and Kill exposes how Weinstein leveraged his wealth and influence, which extended to the upper levels of NBC and the Manhattan district attorney’s office, to create a culture of impunity around him. Where She Said represents an ode to journalism, Farrow’s book has the cloak-and-dagger pacing of a thriller.Farrow plunges readers into an ugly world where power is deployed against women to coerce, abuse, and silence them. His book is notable for articulating an ethical stance on treating survivors’ stories with dignity, one deepened by his family experience. His sister Dylan Farrow claims their father, Woody Allen, molested her when she was a child, which Allen denies. Farrow believes his sister, and he delineates the long-term effects of trauma on survivors and the power of breaking silences.

Know My Name, Chanel Miller

Until she made her identity public by publishing this memoir, Chanel Miller was known as “Brock Turner’s victim” and “Emily Doe,” the pseudonymous author of the searing victim impact statement published with her permission on BuzzFeed. In Know My Name, Miller shares the story of her sexual assault, trial, and recovery. “You don’t know me,” Miller’s statement began, “but you’ve been inside me, and that’s why we are here.” Addressed directly to Turner, who was convicted on three counts of felony sexual assault for violating her behind a dumpster outside a Stanford fraternity house, Miller’s statement was raw. She recounted waking up in the hospital with no memory of the attack. She learned about the extent of her violation when she read about it online. The book is organized in three parts: the attack, the trial, and Miller’s struggles in the aftermath of the verdict. Know My Name indicts a legal system that allows defense teams to bully survivors and dole out light sentences to convicted rapists. The maximum sentence was 14 years; Judge Aaron Persky gave Turner six months. He served three. Persky’s sentence meant Turner received a summer’s worth of punishment for what Turner’s father called “20 minutes of action.” Miller’s memoir is explicit about rape and rape trials, and the last third of the book attests to the hard-won recovery of her voice and agency.

Indelible in the Hippocampus: Writings from the Me Too Movement, edited by Shelly Oria

In her testimony about being sexually assaulted by a drunken, teenage Brett Kavanaugh, Christine Blasey Ford was asked by Sen. Patrick Leahy (who also served on the Senate Judiciary Committee when Anita Hill testified that Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her) what stayed with her from the attack. Ford replied: “Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter.” This memorable line provides the title for a collection, edited by Shelly Oria, of MeToo poetry, essays, and fiction. Indelible is an archive of material that has not been filtered through reporting or shaped by legal proceedings. The selections immerse readers in a range of responses to sexual assault and the aftermath of trauma. Anthologies have the built-in benefit of supplying context through aggregation. Many readers are accustomed to following individual cases of sexual violence in the news, as with the Weinstein story, or of reading an essay or two by survivors. But Indelible in the Hippocampus—just like the viral trending of #MeToo on social media—provides evidence of the scale of the problem.

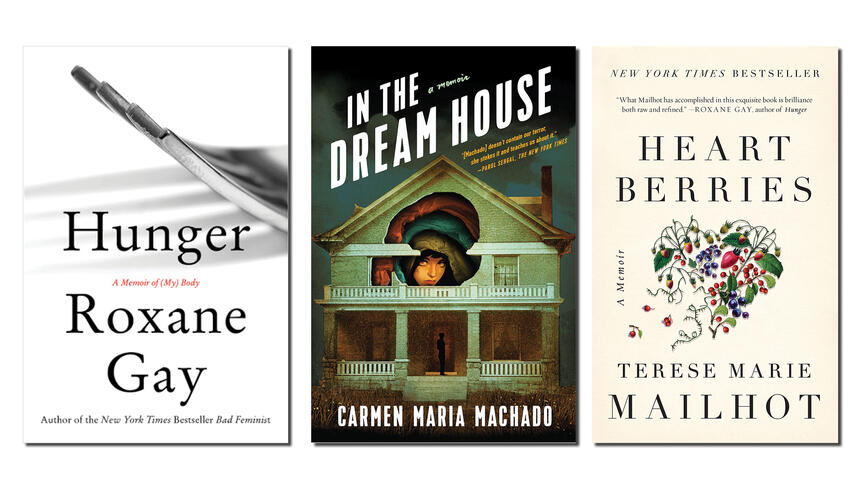

Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, Roxane Gay; In the Dream House: A Memoir, Carmen Maria Machado; Heart Berries: A Memoir, Terese Marie Mailhot

Many readers turn to memoir for meaningful stories about the complexities of hardship and resilience. Memoirs that break shaming silences about sexual abuse occupy an important place within life writing about MeToo. They provide a way to engage with the scale of violence revealed by the millions of #MeToo tweets by connecting it to a particular life, community, and history. Survivors in very different circumstances, linked only by the ubiquity of sexual violence in women’s lives, offer perspectives on race, sexuality, Indigeneity, and the power of writing to transform pain. A longer MeToo story lies behind the headlines. First-person writing in the form of memoir, commentary woven into investigative journalism, and online writing represents a genre of MeToo literature that is changing the conversation about sexual violence. First-person writing provides an important counterweight to the fast-paced journalism of breaking stories. It builds upon the personal, collective, and testimonial power of anyone to say “Me Too.” Survivor testimony represents the scales of violence even as the scales of justice often fail to.