Wellesley and the University of Oxford Team Up to Research Political Polarization in the Digital Age

While political polarization existed long before the advent of the internet, online political polarization is a recent phenomenon that has spread with the rise of social media. Wellesley’s Social Informatics Lab, run by Takis Metaxas, professor of computer science, has teamed up with the University of Oxford’s Centre for Technology and Global Affairs to study how political polarization is evolving and how it manifests itself across social media, using Brexit and the Catalan Independence Movement as focal points. Below, Metaxas discusses their research and the importance of understanding online polarization during this time of rising authoritarianism around the globe.

Q: Both computer scientists and political scientists are involved in this research. Why is interdisciplinary collaboration important when trying to understanding online polarization?

Takis Metaxas: Political polarization has existed for many years, but unfortunately, understanding its recent online properties has not been as intuitive as we might hope. This problem has increased in complexity and magnitude due to social media, that has changed the nature of rumor dissemination, and thus polarization, in several key ways: It has allowed rumors and opinions to spread faster, more cheaply, and more expansively, in turn passing these characteristics on to online polarization. Additionally, it has afforded easier access to opinions of online actors that they might otherwise sparsely observe, and even then, observe with less clarity.

A team of four Wellesley students (Anna Kawakami ’21, Yu-jin Cho ’21, Kat Swint ’22, and Sarah Pardo ’22) is working with our colleagues at the Center for Technology and Global Affairs at Oxford University, which is also supporting and funding the research along with Ravi Ravishankar and Sam Finn, two of my colleagues from Library & Technology Services. An interdisciplinary approach to understanding online polarization is necessary because the ramifications of online polarization are highly consequential. In the past, the democratic discourse was largely confined to traditional media sources, but the internet has allowed users to become content creators as well as audience members. By transforming the nature of democratic discourse through social media, members of the electorate assess information differently, which in turn influences their decision-making in major partisan political debates, such as Brexit. Thus, an interdisciplinary approach is important not only to comprehensively measure but also to understand the consequences of polarization on political discourse.

Q: Can social media actors affect the degree of social media polarization independently of offline events, or are they ultimately bounded by what occurs in “real life”?

Q: Can social media actors affect the degree of social media polarization independently of offline events, or are they ultimately bounded by what occurs in “real life”?

Metaxas: This is a good question, one we decided to tackle in the Brexit data collection. To test whether this is true, it is important to measure the amount of online activity when “non-online” events are relatively quiet, for example over holidays and times Parliament is not in session. We did find a rise in polarization and a rise in agitation from the more visible actors on both sides of the Brexit debate over Easter break when Parliament was in recess. This suggests that social media polarization can happen independently of real life, brewing its own storm. It also suggests that when fewer people participate in online discussions, the more extreme members of each group are sounding the loudest. I think journalists should be aware of that, because it is during such quiet periods that they are trying to find news worth broadcasting. They may be amplifying even more the online agitators because they can “hear” them better!

Q: Do different types of agitators (for example, individuals or organizations) produce different degrees of social media polarization?

Metaxas: For Brexit, we have found so far no evidence to support that organizational and individual accounts produce different degrees of social media polarization. To determine this, we compared the two groups’ distributions of their mean agitation coefficient, which quantifies a social media agitator’s effect on the direction and degree of the polarization measure. The fact that they were not statistically significant was a surprising result, given that there were significantly more individuals than organizations in our dataset (a ratio of 17:1). In the future, we aim to understand what factors may have caused this result, through conducting a comparative study of individual and organizational accounts.

Q: What are some questions you are hoping to answer in the coming year?

Metaxas: What I worry about is that communication technologies combined with the power of artificial intelligence are increasing the influence of online provocateurs and propagandists and creating greater polarization. Democracy depends on the ability of its citizens to talk to each other and be persuaded by each other using logical arguments; it is hurt by populists, provocateurs, and propagandists who want to create high emotions and bypass logic. The more we can understand their technological means and techniques in sowing divisiveness, the better we can defend democracy. In the process, we need to understand better how people make decisions and how they can educate themselves so as to recognize propaganda. It is really an important question since the birth of democracy, but we are making progress in understanding its complexity in a more complex world.

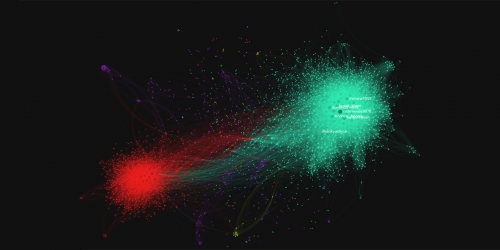

Photo: Visualization detail from Brexit Twitter data taken on January 29, 2020.