Trends to Watch in the Next Decade, Part 2: Families and Climate Change

In a two-part celebration of the new decade, we asked faculty members from across Wellesley to share insights about what trends we can expect to see in their fields over the next 10 years (read part 1). Check out how a few of them responded:

Families and reproduction

Rosanna Hertz, Class of 1919 50th Reunion Professor of Sociology and Women’s and Gender Studies

- In the next 10 years we are likely to see more women waiting to have babies, and then more women likely to need technologies to help them have babies. We know that women who are middle class—regardless of race—are already accessing these reproductive technologies (such as I.V.F), and they will continue to do so. Hopefully, women who are part of the working class or poorer women who have fertility issues will be able to access medical services, and I hope that we work toward reproductive equality. It is likely that the meanings of “mother” and “father” will become varied, or perhaps we will have a new language for all the people who might help to create our children, including not only the people who donated their genetic material, but also gestational carriers. But even if we acknowledge these other contributors to making a baby, we are also likely to continue to live in nuclear families (with two parents—mom and dad, mom and mom, dad and dad—or a single mom and, more recently, single dads). These “others” will be important, and some contributors might also help raise the child or have certain times for them to be involved with the child. I imagine legal parentage expanding in new ways and the laws changing to reflect these new realities. Finally, we will also see the growth of egg freezing as a booming business and as a strategy individual women will opt to use to be able to establish their careers without jeopardizing motherhood. While this technology seems like a reasonable choice to enhance reproductive options, the use of this technology to fix the lack of social policies around work/family issues is problematic. I hope that women (and men) will continue to push for more supportive workplaces so that we can all advance to our fullest potential while also having children.

- As the internet grows in all kinds of yet-to-be imagined ways, we can expect more people to locate their genetic relatives—but these are people are strangers—and in many cases they will be forming new relationships on the basis of shared genes. These connections are already changing and expanding who counts as family and how we think about kinship. These loose knit networks will continue to grow and might well rival conventional extended families.

Climate change and conservation

Andrea Sequeira, professor of biological sciences

-

In the decade ahead, please welcome conservation genomics! Conservation science is advancing by harnessing the power of molecular biology and generating the new area of conservation genomics. The concerns around species losses are well justified. We are losing global biodiversity at a much faster rate than natural extinction. The culprits are varied: changes in land use, unsustainable use of natural resources, invasive alien species, climate change, and pollution, among others. With an ease never seen before, we are obtaining nuanced information about the genetic acumen of threatened populations and species of non-model organisms. The revolution has come about with the development of advanced high-throughput techniques that look at the whole genome (such as reduced representation sequencing: RAD-Seq) and have become the most widely used genomic approach in conservation studies. Genomic methods can yield information on species identity; determine how likely it is that introduced species may be hybridizing with local ones; and provide estimates of effective population size in threatened populations.

-

I foresee that future practitioners of conservation science will benefit from a convergence of different skills. Women in particular who can bridge expertise in technically challenging areas, such as molecular biology and data science, but also excel at communicating and bringing to life the fundamental importance and urgency of the biodiversity crisis, will be our best advocates.

Becca Selden, assistant professor of biological sciences

-

At this point, it is not a question of whether oceans will warm in the next decade—that reality is now. We are already seeing the devastating effects of warming on coral reefs and other key marine ecosystems. As we approach the level of emissions at which we will be locked in to at least a 2 degrees Celsius global warming, the effects of climate change on the ecosystems that we have studied for decades are likely to be ubiquitous. What we do in the next 10 years will define life on Earth and in the oceans as we know it for generations to come. We are at a critical crossroads, and now is the time to use our scientific understanding to take action, both to work to reverse those changes as well as to anticipate and mitigate the future effects on marine ecosystems, fisheries, and the diversity of ways that oceans benefit society.

-

Social media will be an important, growing, and permanent part of the scientific landscape, especially for climate change. The benefit of the short format on a platform like Twitter is that it requires scientists to distill their stories into a key message that is accessible to a broad audience. The risk is that it can become an echo chamber. But, I think the biggest way that social media has had an impact is in its ability to add more voices to the public discourse about environmental issues—especially young people, early-career scientists, and female scientists. Having more voices at the table means that we get not only a fuller picture of the impact of climate change on communities, but also a richer set of experiences and backgrounds to inspire creative solutions. Young activists like Greta Thunberg will continue to pave the way for more young people to become the face of this issue and its solutions. Climate change is truly the challenge of this generation. I am hopeful that we rise to that challenge.

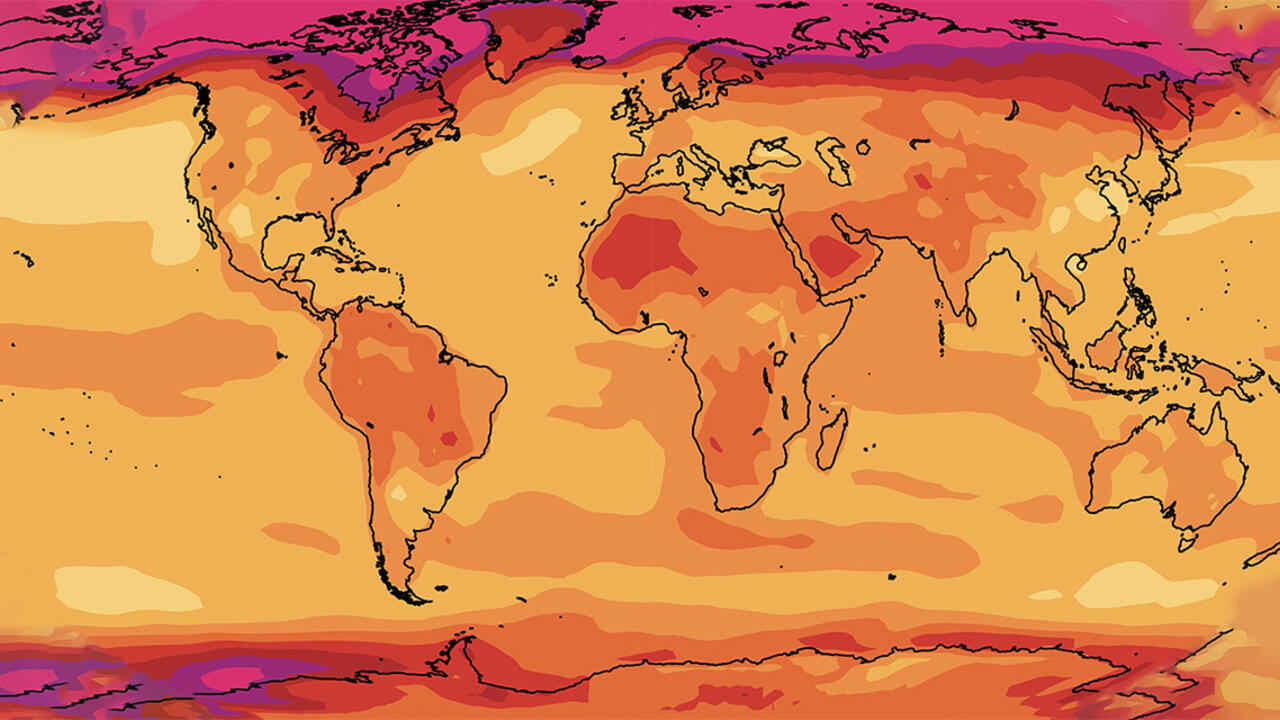

Photo: This heat map shows that the global temperatures have increased 1 degree Celsius on average due to anthropogenic climate forcing. Temperature increases range from 0 (lightest areas) to 1.8 degrees celsius (pink).