Exhibit Curated By Courtney Sato '09 Offers Important Reminders of U.S. Treatment of Japanese-Americans During WWII

An exhibit curated by Courtney Sato '09 offers a new perspective on the internment of thousands of Japanese-Americans during World War II, something now widely acknowledged as an historic injustice. The Yale University exhibit, which was covered by the New York Times, sheds light on this dark time in U.S. history when an estimated 120,000 people of Japanese descent, about two-thirds of them United States citizens, were incarcerated after the Pearl Harbor attack. The exhibit comes at a time when heated debates are taking place throughout the country and around the world about immigration.

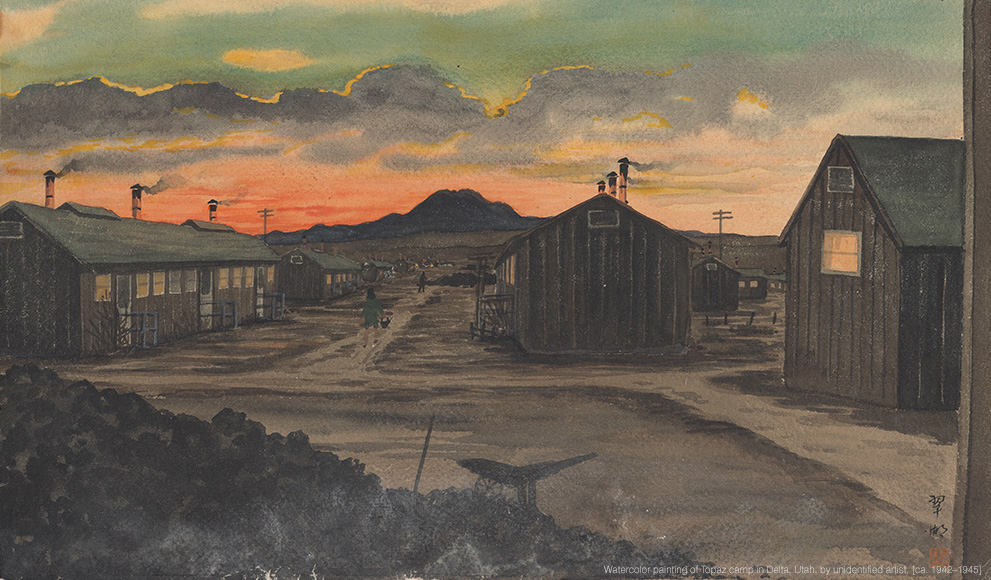

"Out of the Desert: Resilience and Memory in Japanese American Internment," Sato's first curated exhibit, is on display at Yale's Sterling Library through Feb. 26. It features nearly 100 items depicting what life was like in internment camps; included are letters from those in the camps, archival photographs, artwork, and official documents. Sato and her partner Corey Johnson have also created an extensive digital archive to supplement and extend the exhibit. She completed the exhibit as part of her doctoral work in American studies at Yale.

According to the Times, "The exhibition focuses on the resilience and creativity that helped many detainees survive the forced removal from their homes and jobs and the harsh conditions in remote camps that were ringed by sentry towers with armed guards." The story continued, "There is poignancy in images like a schoolteacher's snapshots of internees' gardens and an unknown watercolorist’s painting of a sunset over the Topaz internment camp in Utah."

Sato said her Wellesley years were very much on her mind throughout the curatorial process. "I continually reflected on how my initial interest in Asian American studies actually began at Wellesley through classes I took with Professor Yoon Sun Lee [Mildred Lane Kemper Professor of English]," she said. She also cited her work advocating for Asian American studies at Wellesley through participation in the Wellesley Asian Alliance (WAA).

The exhibit came into being after Sato began digging into Yale’s archival collections. "I quickly discovered a large and diverse set of materials related to internment," said Sato. "While Yale's collections include official War Relocation Authority and government documents, my research also revealed…unusual and rare materials like library cards [from one camp]; copies of the official exclusion orders hung around the Presidio in San Francisco notifying Japanese and Japanese Americans of their forcible 'relocation'; handmade Junior Red Cross Scrapbooks; and yearbooks with internee signatures and messages like ‘have a great summer’ scrawled across a photo featuring rows of camp barracks."

The Times specifically noted the persistence required from Sato to track down a former internee, Yonekazu Satoda, whose documents, diary, and other personal artifacts she found in Yale’s archives. Now in his nineties, Satoda was 22 when he and his family were taken from their home in San Francisco and eventually interned at the Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas. Yale acquired Satoda’s materials, including the diary, five years ago but curators were not able to contact Satoda at the time. He told the Times that he had not seen or thought about the diary since 1945.

Sato said she felt the artifacts were essential for the exhibit because they provided rich examples of life in the camps but ethically she knew she needed his permission to include them, especially because of the sensitive nature of the diary. She said, "I think the diary is the most meaningful item in the exhibit, because it captures the banality and monotony of everyday life in camp."

Sato said the individuals and stories the archived materials documented became the driving impetus behind the exhibit. "Unlike conventional understandings of internment camps as barren and desolate spaces, these materials chronicled a proliferation of creative production—resilience under harsh conditions, as well as space for alternative narrations of this history," she said.

The exhibit has made it possible for Sato to meet former internees or individuals whose family members were interned, some of whom have traveled from as far away as Canada to view the exhibit. "Many have shared with me that seeing the exhibit led to digging up old photos, mementoes, and letters and discussions with family members," she reported.

Sato said the exhibit’s focus must be placed in context of the current debates. "Internment remains all too salient given the current 'refugee crisis'" and the charged politics surrounding it, she said, adding, "Japanese American internment remains a sad, but little-understood footnote to American history." She said she hopes the exhibit, and its ongoing digital site, can counter this gap in historical knowledge and can inform how we grapple with current issues.