WCW Scholar and Leader Recognized for Bringing Important Concept into Public Discourse

Since the late 1980s, the term white privilege has entered popular discourse around experiences of race, cropping up everywhere from academic articles to Buzzfeed quizzes. This week in the New Yorker Page-Turner blog, Joshua Rothman writes about and interviews Peggy McIntosh, Ph.D., associate director of the Wellesley Centers for Women (WCW), founder of the National SEED Project on Inclusive Curriculum, and the woman credited with coining the term.

While the concept and its variations have been in discussion for some time—indeed, at least as far back as W.E.B. DuBois—the magazine gives McIntosh the nod for bringing it and the handy term to popular consciousness. As the New Yorker describes this concept of privilege, “some people benefit from unearned, and largely unacknowledged, advantages.” A women’s studies scholar who focuses on issues of gender, multiculturalism, and inclusion, McIntosh began thinking critically about how unconscious advantages shape perspectives when she was leading faculty seminars at the WCW.

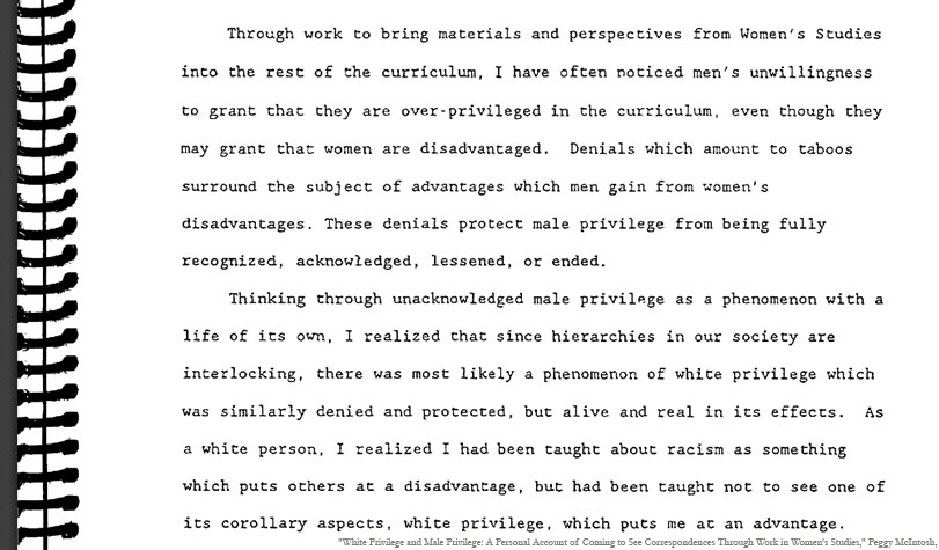

In 1988, McIntosh wrote an influential paper entitled “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women’s Studies.” Unusually for the time, she included a list of 46 highly personal examples of white privilege. She prompted a national discussion about the topic, one that continues through today. After writing this paper and others, McIntosh went on to create the National SEED (Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity) Project, which works with schools across the country to create and implement multicultural and gender-balanced curricula.

“In order to understand the way privilege works, you have to be able to see patterns and systems in social life, but you also have to care about individual experiences,” says McIntosh. “I think one’s own individual experience is sacred. Testifying to it is very important—but so is seeing that it is set within a framework outside of one’s personal experience that is much bigger, and has repetitive statistical patterns in it.”

Read the full interview in the New Yorker online.