Free and open to all from Tuesday to Sunday 11 AM to 5 PM. The Davis is closed on Mondays and holidays.

in Contemporary Culture

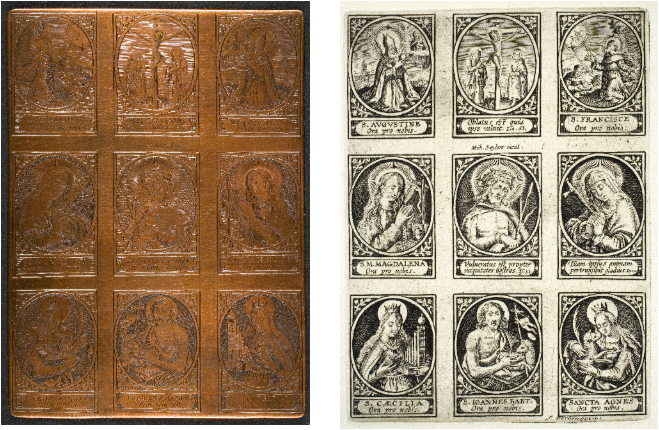

Susanna Verbruggen, Copper plates and engravings, 16th century (or 17th?), 2005.57 and 2005.62, 12.9 x 9.4 cm; 33 x 25.4 cm; 37.5 x 27 cm; 33.7 x 25.4 cm.

Artists and theologians continue to explore Mary Magdalene's multiple identities as a prostitute, madwoman, and apostle. Popular portrayals still emphasize her sensuality, even in her ecstasies. Dan Brown's popular 2003 novel The Da Vinci Code reduced her relationship with Christ to a carnal one. This image persists despite Pope Paul VI’s 1969 declaration that she should be celebrated as a disciple and not as a penitent, as the Church would no longer consider her a repentant prostitute. The decree of June 3, 2016 of Pope Francis I reinforced this idea and underlined the importance of the saint.

Artists’ fascination with Mary Magdalene demonstrates her significance as the object of great devotion over many centuries. Susanna Verbruggen's engraving places her in the same position as the Virgin. The inscription under her portrait, “Ora pro nobis” (“Pray for us”), shows that many believers saw her as an intercessor for their salvation. Engravings like this spread her image, increasing her popularity. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, media like film have introduced new images of Mary Magdalene, all the while building on old ideas of the penitent saint. Films in which her character appears include Norman Jewison's Jesus Christ Superstar in 1973 (taken up again in 2018 by David Leveaux and Alex Rudzinski) and Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ in 1988. On the contrary, Garth Davis' Mary Magdalene in 2018 is based on the Gospel of Mary and presented her as a disciple and an apostle.

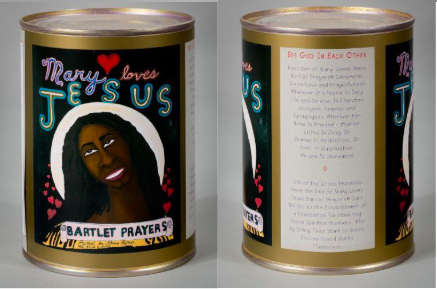

Meg Henson Scales, Mary Loves Jesus Bartlet Prayers, 1997, Mixed media from a painting by the artist, 11.7 x 8.5 x 8.5 cm, 2000.16.1-10.

The depictions of Mary Magdalene in art have had great impact on the lives of Christian women. The ambiguous, contradictory role conferred on her by the Church affected views on women in the institution. More recently, Christian women have argued that if Mary Magdalene was indeed an apostle, nothing seems to justify the exclusion of women from the clergy. She thus enables a feminist re-appropriation. In her series of 1008 painted and labeled cans Mary Loves Jesus Bartlet Prayers, Meg Henson Scales was inspired by the Gospel of Mary. As she explained in the exhibition catalog Divine Mirrors: the Virgin Mary in the Visual Arts, she saw in the injustices suffered by Mary Magdelene those suffered by “many of us” because of sexism and racism. With these cans, the artist emphasized the importance of this saint who is, according to her, the true messenger of Christ.

Conclusion

These artworks in the Davis Museum’s collections illustrate how the confusion and ambiguity in Mary Magdalene's biography has allowed artists to construct her identity in strikingly divergent ways. Often represented as a courtesan, sinner, or prostitute, she demonstrates how misogynistic traditions sought to control women’s sexuality. However, she has also consistently been the subject of a strong devotion. The debates concerning her status and the roles of women in religion and culture continue, making Mary Magdalene, in all of her guises, our contemporary.