Free and open to all from Tuesday to Sunday 11 AM to 5 PM. The Davis is closed on Mondays and holidays.

Lover

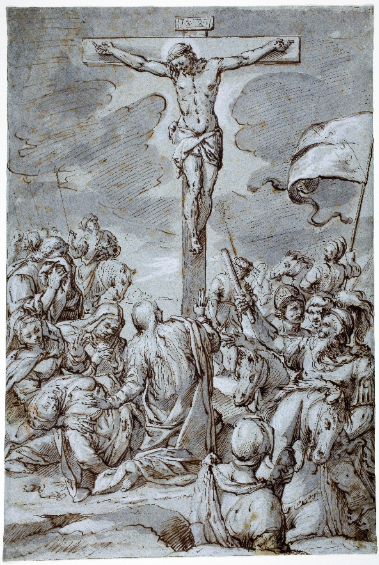

Hans Von Aachen (1552-1615), Crucifixion, Late 16th/early 17th century, Pen and brown ink, gray wash with white gouache highlights over black chalk underdrawing, 41 x 27.7 cm, 1979.18.

According to the Bible, most of his disciples abandoned Christ at the time of the crucifixion, but Mary Magdalene followed him to the cross. The love that she felt for Christ is sometimes perceived as spiritual, a metaphor for the reunion of Christ and the Church. It has also been portrayed as earthly and carnal. In this drawing by the mannerist artist Hans Von Aachen, the diagonal created by the gaze exchanged between Christ and the Magdalene underlines their relationship. At the foot of the cross, she and the unruly crowd around her symbolized the incarnation of the sins for which Christ will offer redemption through his death.

Andrea Mantegna (1430-1506), Entombment of Christ, circa 1470 or 1490, Engraving on greyish-white laid paper, 30,6 cm x 44,9 cm, 1958.21.

Andrea Mantegna was one of the first renowned Italian artists to take an interest in engraving in the mid-fifteenth century through his contacts with the German community living in Italy. In this work, he emphasized the tragic mourning of Jesus’s loved ones at his burial. Mary Magdalene’s face contorts in a paroxysm of pain. She looks at Christ's dead body and surrounds it with her despair, her arms raised in the air, her hair underlining the tumult that inhabits her. Her mouth, opened wide, echoes the darkness of the cave that will receive the corpse.

***

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Crucifixion (round), 1519, Engraving, Diameter: 6.6 cm, 1975.50.

Albrecht Dürer's smallest known engraving, this design was probably created for Emperor Maximilian for a now lost gold medal for a hat or the knob of a sword. Dürer would have made several impressions in addition to the one given to the emperor. In the image, Mary Magdalene sits at the foot of the cross, embracing the wood and looking at Christ. Unlike Jesus, John, and the Virgin, she has no halo. We can recognize her by her long hair and her position, which is often represented in the iconographic tradition. Indeed, she lacks the kind of veil worn by the other women in the crowd. Her posture manifests both pain and love—and suggests a carnal embrace. Her strong, central gaze affirms her role as a witness.