Free and open to all from Tuesday to Sunday 11 AM to 5 PM. The Davis is closed on Mondays and holidays.

Farmers and Workers

Artists often create images of the working class for elite collectors rather than for the workers themselves. Idyllic scenes of healthy peasants enjoying the harvest or operating traditional machinery, or featuring gainfully employed workers in more industrial contexts, confirmed the dignity of labor, but also provided visual confirmation that the social order was at peace, with no need for strikes or revolts. At times, modern artists have envisioned themselves as workers or craftspeople just as noble as carpenters or masons. During the troubled 1930s, however, artists depicted other workers whose lives could not be so easily idealized: unemployed men roaming the streets, bundled up against the cold, or displaced and deported because of the economic crisis. Contemporary artists might expose the plight of workers trapped in cycles of oppression and abuse, like the informal miners of Brazil, or dissect the modernist belief that the worker controlled his or her destiny.

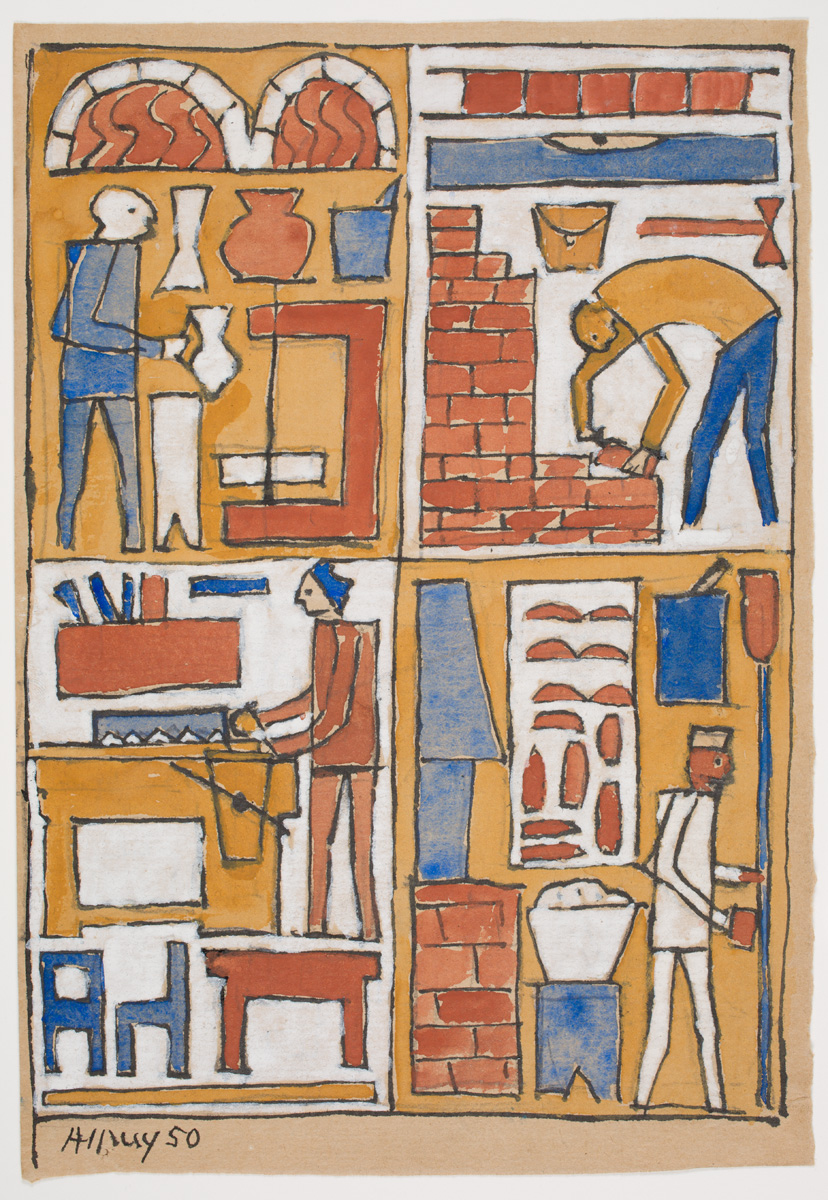

Julio Alpuy (Cerro Chato, Uruguay 1919 – 2009 New York, New York), Untitled, 1950, Black ink and watercolor, Gift of Joanna Alpuy 2011.58. © Fundación Julio Alpuy.

This watercolor by Julio Alpuy is part of a large study collection donated to the Davis Museum by the artist’s widow. It relates to a series of Constructivist murals he created in the mid-1950s, including one for the modernist residence of Uruguayan architect Mario Payssé Reyes. Alpuy, like all of Torres-García’s students, resisted the role of the artist as genius, which diminished artisans by assigning them a lower status. His profound respect for craft is reflected in this sketch, which features a baker, potter, mason, and carpenter. Alpuy knew the latter trade particularly well; after moving to New York in 1960 he used his carpentry skills to earn a living.

Milton Rogovin (Brooklyn, New York 1909 – 2011 Buffalo, New York), Mexico, 1988, Gelatin silver prints, Gift of Denise Jarvinen (Class of 1983) and Pierre Cremieux in memory of Karl E. “Chip” Case, Professor Emeritus of Economics 2016.382-.383. Courtesy of the artist.

Predominantly self-taught, Milton Rogovin began taking photographs in the 1950s to illuminate social inequities and the lived experiences of the people he called “the forgotten ones.” He traveled the world for his Family of Miners project (1981–90), drawing attention to experiences shared by women and men who sustain themselves and their families despite challenging and sometimes exploitative conditions. With empathy and respect, he created portraits of miners alone at their worksite and again at home, with their families, revealing the material realities of their daily lives.

Alfredo Jaar (b. 1956 Santiago, Chile), Frame of Mind, 1987, Suspended lightbox with color transparency, mirrors, and gilded frames, Museum purchase, The Class of 1947 Acquisition Fund 2003.174. Courtesy of the artist.

To create Frame of Mind, Alfredo Jaar selected a single photograph from a collection of over 1,000 he had taken at Serra Pelada, Brazil—then the largest open-pit gold mine in the world. Depicting a vast landscape filled with workers who appear at the scale of ants, Jaar’s picture addresses the difficult enterprise of extracting precious metal from the ground without modern machinery. In the installation, the photograph faces downward, casting a reflection onto the grid of framed mirrors. This unexpected mode of presentation complicates the physical act of experiencing the photograph. For Jaar, an image is not simply a representation, but a site to be mined and dissected.

Jorge Satorre (b. 1979 Mexico City, Mexico), Párrafo justificado a la izquierda o la democracia en el cruce de caminos (Paragraph Justified on the Left or Democracy at the Crossroads), 2012, Graphite, Museum purchase, Erna Bottigheimer Sands (Class of 1929) Art Acquisition Fund 2013.31. Courtesy of the artist.

Most of Jorge Satorre's works appropriate historic moments, lost narratives, or even natural events and use them as springboards for fresh analysis. This graphite drawing, at once rational and humorous, separates and rearranges the images in Diego Rivera's Man, Controller of the Universe (1934), a mural in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. Painted during the worst years of the Depression, Rivera's fresco compared an idealized Communist world to a vilified Capitalist one. By rearranging the elements, Satorre questions the visual and rhetorical integrity of Rivera's mural, and especially the power of the worker to control his or her own destiny.