Free and open to all from Tuesday to Sunday 11 AM to 5 PM. The Davis is closed on Mondays and holidays.

Rural and Urban

Across a region of such geographic and cultural diversity, there is surely no such thing as a quintessential Latin American space, whether rural or urban, real or imagined. Artists have responded to the pre-Columbian past, signaled by the restored pyramids of Teotihuacan in Mexico and the interlocked stonework of the Inca in Peru. They have depicted landmarks of the colonial period, such as monumental aqueducts or Baroque churches looming above agricultural fields. Many of these artists were visitors, purposefully excluding signs of modernity from their idealized representations of the rural world. There were also those who focused on the city and the impact of rampant urbanization and industrialization by poetically capturing the melancholic juxtapositions of contemporary life. Apartment blocks and skyscrapers crowd or even threaten the city’s residents, or reveal the fact that modern architecture is pretty much the same everywhere in the world. The automobile might be part of an endless loop in the race to development or a nostalgic window onto a city falling into pieces.

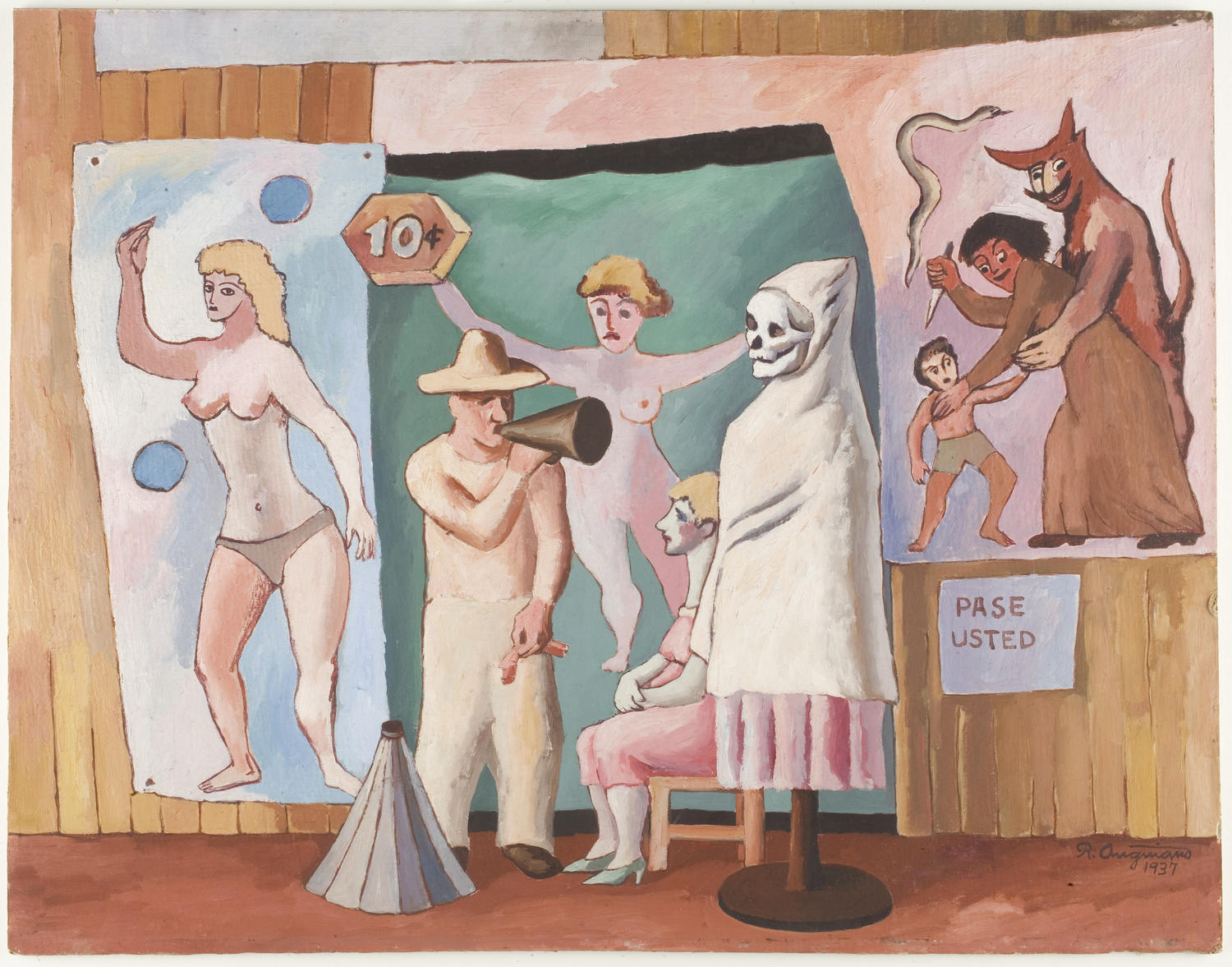

Raúl Anguiano (Mexico City, Mexico 1915 – 2006 Mexico City, Mexico), La carpa (Tent Show), 1937, Oil on cardboard, Gift of Brigita Anguiano 2010.55. Courtesy of the artist's estate.

Along with political posters and prints, Raúl Anguiano created a series of melancholy works inspired by itinerant circuses and vaudeville shows held in temporary structures or carpas. These poetic and personal paintings were partly intended for sale in the growing (and mainly US-based) market for modern Mexican art. Family-run carpas appealed mainly to working-class audiences. In this scene, one painted banner advertises the presence of titillating performers while the other may serve to warn curious boys not to steal a peek at the sexually explicit show within.

Víctor Rebuffo (Turin, Italy 1903 – 1983 Buenos Aires, Argentina), Liberación (Liberation), 1943, Woodcut, Museum purchase, John McAndrew Fund 2006.53

Víctor Rebuffo, one of the most prolific artists working in twentieth-century Argentina, created numerous prints featuring the working class, in which the urban landscape plays a central role. In the early decades of the twentieth century, Buenos Aires was rapidly transformed by tall apartment buildings, factory chimneys, and especially electrical and telephone wires, symbolic of new communication systems. In Liberation the cables may transmit demands for working class unity across the city.

Ann Parker (b. 1934 London, England), Country Boy in front of National Palace Backdrop, Sololá, 1970s, Silver-dye bleach print, Museum purchase, Ina Brown Ramer (Class of 1956) Endowed Fund for Acquisitions and Educational Program Support 2016.105. Courtesy of the artist, © Ann Parker, Courtesy Deborah Bell Photography, New York and Paul M. Hertzmann Inc., San Francisco.

Throughout the 1970s, US photographer Ann Parker documented the work of itinerant photographers across Guatemala. Here the unexpected juxtaposition of the boy’s traditional Maya clothing and the cityscape behind him—which shows the capital’s main square—might be read as an affirmation of civic pride or perhaps of citizenship, though not necessarily evidence of a desire to move to the city. Parker’s photograph demonstrates a basic desire for self-representation at a time when government repression was annihilating Maya communities, leaving many men to abandon, forever, their extraordinary embroidered costumes.

Lorenzo Homar (San Juan, Puerto Rico 1913 – 2004 San Juan, Puerto Rico), Paisaje obrero (Workers Landscape), 1961, Woodcut and silkscreen, Gift of Martina Schaap Yamin (Class of 1958) 2017.230. Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

Lorenzo Homar has long been recognized as the “maestro” of Puerto Rican printmaking, and Workers Landscape is a rare early example of his work. The industrial scene may depict the Commonwealth Oil and Refining Company, a vast government-sponsored petrochemical plant that began operation in 1956 on Puerto Rico’s southern coast. However, rather than show the refinery teeming with workers, Homar presents us with a desolate industrial wasteland with a lone fisherman rowing his boat across a bay. Workers Landscape is one of the first works of activist art that drew attention to the danger of big oil on the island’s economy and environment.

Francis Alÿs (with Juan García and Emilio Rivera) (b. 1959 Antwerp, Belgium), Cityscape, 1996-97, Oil on panel and synthetic polymer paint on sheet metal, Museum purchase with funds provided by Wellesley College Friends of Art 2010.94.1-.3. Courtesy of the artist.

Belgian-born artist Francis Alÿs has lived in Mexico City since the 1980s, operating out of a studio in the congested colonial center. He finds inspiration in Mexico’s historical and cultural density, where past and present, tradition and modernity, engage in a continuous and sometimes chaotic conversation. The Cityscape triptych consists of a small painting by the artist and two larger versions commissioned from professional sign painters. Each depicts non-descript architectural elements found in any modern metropolis, but the compositions are not identical. Although Alÿs orchestrated the entire project, each version is a personal interpretation resulting from dialogue and interchange, like jazz musicians riffing on an original theme.