Free and open to all from Tuesday to Sunday 11 AM to 5 PM. The Davis is closed on Mondays and holidays.

Saints and Rituals

Believers or not, modern artists could hardly avoid the cultural impact of Catholicism, shared across Latin America. Evangelization of the indigenous populations had been an essential part of the Conquest, and artists sometimes rooted national identity in this colonial past, when Spanish friars ministered to suffering indigenous populations and replaced old gods with new saints and rituals. By the twentieth century, priests might be seen as benevolent or reactionary depending on an artist’s political position. In Mexico and Cuba, despite the anti-clericalism of revolutionary governments, much of the populace remained devout, and contemporary portraits draw strength by alluding to Catholic saints and martyrs. The Virgin of Guadalupe emerged as an enduring symbol of cultural pride, especially among Chicano/a artists in the United States. Across the Americas, Catholicism confronted other religions, including those of the African diaspora, resulting in syncretic religions like Cuban Santería, a tradition mined by contemporary artists from the island.

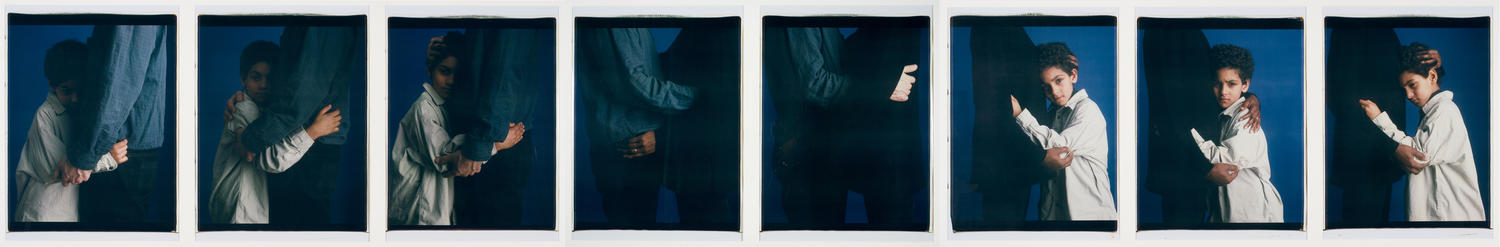

María Magdalena Campos-Pons (b. 1959 Matanzas, Cuba), La Sagrada Familia (The Holy Family), 2000, Dye diffusion transfer prints (Polacolor), Museum purchase, The Dorothy Johnston Towne (Class of 1923) Fund 2000.84.1-.3. Compliments of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco, CA.

In her work, Cuban-born María Magdalena Campos-Pons addresses the legacies of slavery, separation, and exile. The Holy Family—commissioned by the Davis Museum in 1998—sanctifies the biracial identity of her nuclear family. The photographs show the artist and her husband, composer Neil Leonard, with their son, Arcadio. The boy hides his face as he hugs his father (to the left), but expresses varied emotions while embracing his mother (to the right). The title suggests a Roman Catholic altarpiece, but the blue background invokes Yemayá, the Yoruba orisha or goddess, a protector of women, children, parenting, love, and healing.

Abraham Regino Vigo (Montevideo, Uruguay 1893 – 1957 Buenos Aires, Argentina), El religioso or Los bienaventurados (The Religious One or The Blessed), 1920 (printed 1936), Etching and aquatint, Museum purchase, The Class of 1947 Acquisition Fund 2007.88. Courtesy of the artist's estate.

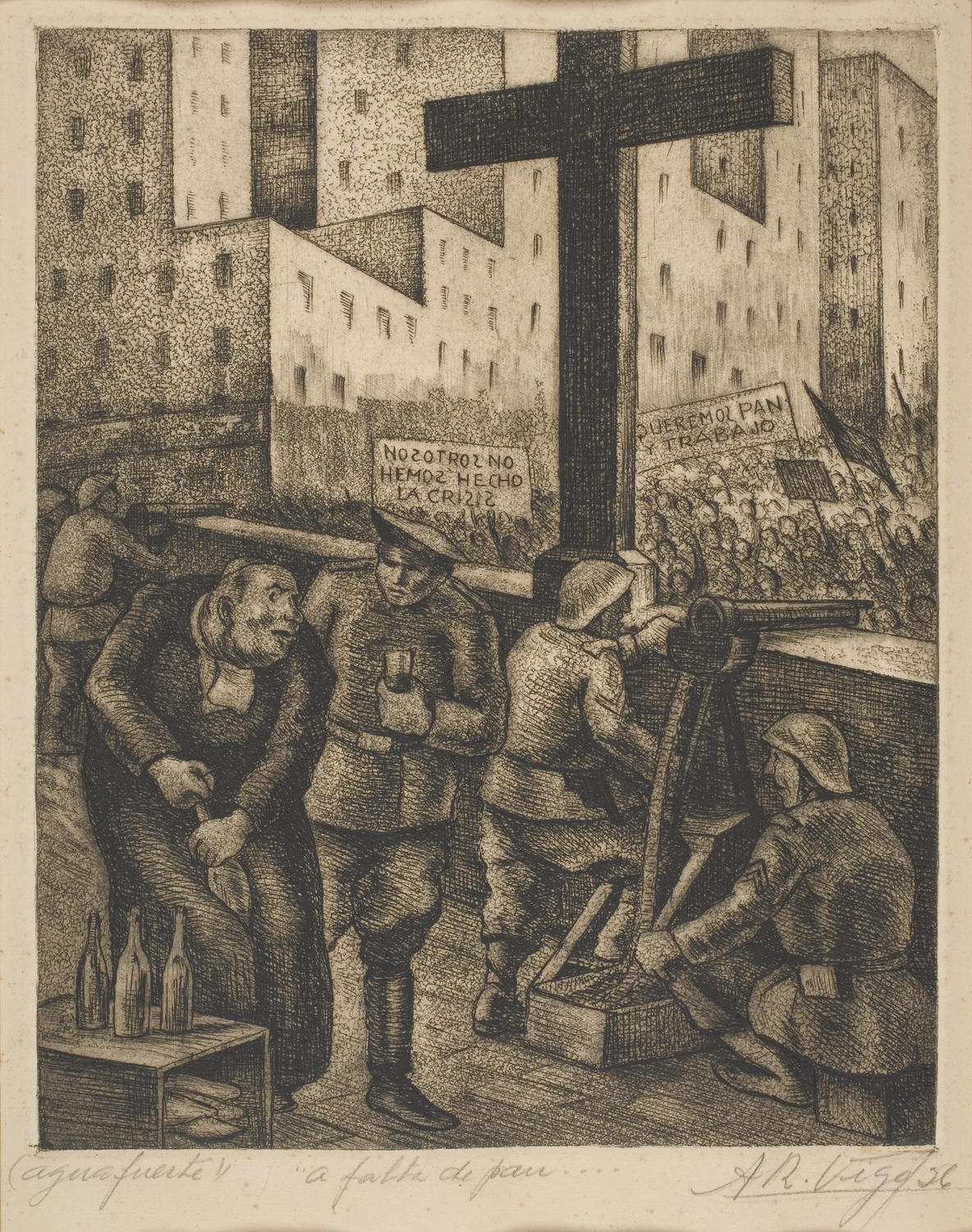

Abraham Regino Vigo (Montevideo, Uruguay 1893 – 1957 Buenos Aires, Argentina), A falta de pan… (For Lack of Bread...), 1936, Etching and aquatint, Museum purchase, The Class of 1947 Acquisition Fund 2007.88. Courtesy of the artist's estate.

These etchings represent different phases in the career of Argentine printmaker Abraham Regino Vigo. The Religious One, from 1920, dignifies the priest and his passive congregants, drawn from the working class. The Davis Museum’s copy is a 1936 re-strike, in which he changed the title to The Blessed. The other etching takes a far more critical view of the clergy, in line with Vigo’s increasing political activism. Workers march towards a church, carrying signs that read “We did not create the crisis" and "We want bread and work.” A priest feeds soldiers bread and wine, giving symbolic communion to the armed defenders of the established order.

René Portocarrero (Havana, Cuba 1912 – 1985 Havana, Cuba), Magic Transfiguration, 1952, Ink and gouache, Gift of Mr. Joseph Cantor 1956.8

In Magic Transformation, three two-dimensional totemic figures, crisply rendered in black ink, appear against a mottled background; the one to the right seems to wear an extravagant headdress. The emergence of magical beings out of the painterly substrate evokes the sacred act of transfiguration. The drawing hints at a variety of Caribbean religious practices animated by divine possession and embodiment, but was also influenced by Surrealist theory.

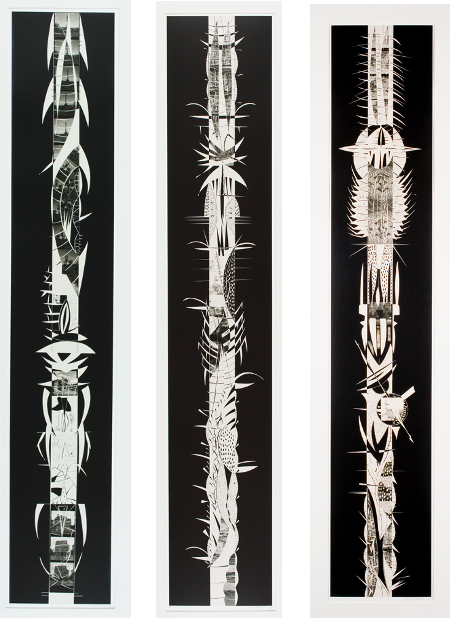

María Martínez-Cañas (b. 1960 Havana, Cuba), Black Totems II, III, and IV, 1991-92, Gelatin silver prints, Museum purchase with funds provided by Wellesley College Friends of Art 2012.52-54. Courtesy of the artist.

Black Totems II, III, and IV are unique works from a series inspired by the paintings of Cuban modernist Wifredo Lam. Martínez-Cañas retained the central sugar cane shafts that structured Lam’s compositions, but transformed his spiky half-moons, horizontal and curved spines, and Afro-Cuban motifs into black and white design elements that contain photographs she had taken in Mexico and Arizona. The mysterious images within the totems call forth memories of voyages and discoveries across the Americas.

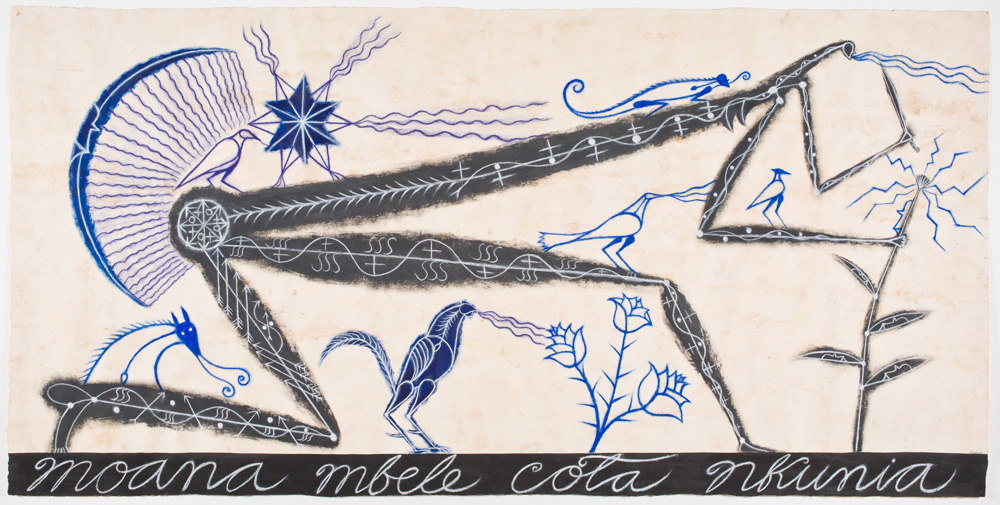

José Bedia (b. 1959 Havana, Cuba), Moana Mbele Cota Nkunia (Knife-Woman Cuts the Branches), 2000, Acrylic and crayon, Gift of Jacqueline Loewe Fowler (Class of 1947) 2001.69. Courtesy of the artist.

Cuban artist José Bedia has lived in Miami since 1993. He has long found inspiration in Native American rituals, the superheroes and narrative captions of comic books, and especially in the Palo Monte belief system, brought to the Americas by enslaved Central Africans. In this work, done on Mexican amate or bark paper, the long-limbed “Knife-Woman” slinks forward, her black body patterned with enigmatic symbols. She prepares to cut a piece of wood, a likely allusion to the spirits embodied in the “sticks of the forest”—a direct translation of Palo Monte. The crescent moon and six-pointed star radiate cosmic energy.