Free and open to all from Tuesday to Sunday 11 AM to 5 PM. The Davis is closed on Mondays and holidays.

Protest and Propaganda

Latin American artists have long been aware of the dangers of propaganda, whether broadcast over public airwaves or whispered by a sinister bureaucrat. Many have used persuasive visual tools to expose social injustice through art. Photographers documented impoverished or suffering victims, down and out on the streets; others captured marches demanding basic urban services or exposing the crimes of a dictatorial regime. Printmakers at the Taller de Gráfica Popular in Mexico lampooned corruption and oppression in easily legible caricatures, printed on satirical broadsides that workers could purchase for pennies, and created posters and fliers promoting working-class unity. More recently, Mexican-American artists have warned consumers of the ecological and human costs of cheap labor and deployed digital technologies to expose police brutality and the deportation of undocumented workers.

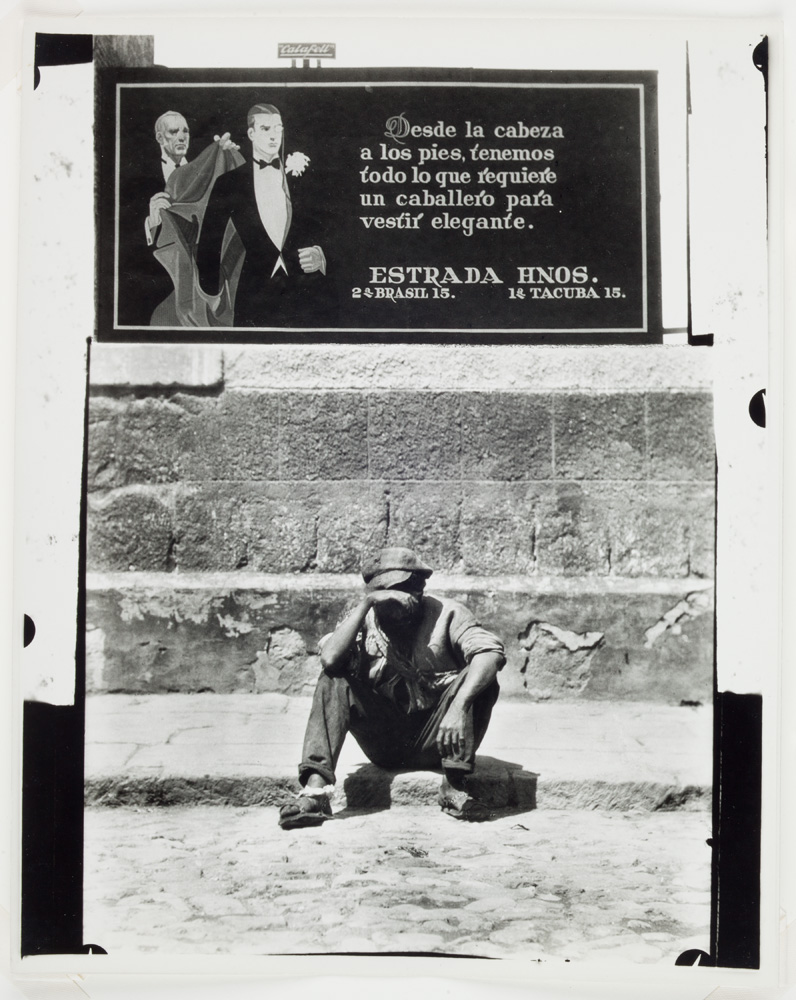

Tina Modotti (Udine, Italy 1896 – 1942 Mexico City, Mexico), Elegance and Poverty, 1928, Gelatin silver print, Museum purchase, The Class of 1947 Acquisition Fund 2014.152

Tina Modotti used photography as a weapon to promote revolutionary reforms and expose the struggles of Mexico’s workers and peasants. In Elegance and Poverty, which first appeared in El Machete, the newspaper of the Mexican Communist Party, a despondent worker sits beneath a billboard advertising a gentleman’s tailor. Or does he? Actually, this is a photomontage: Modotti spliced together two negatives at the billboard’s bottom edge.

Alicia D'Amico (Buenos Aires, Argentina 1933 – 2001 Buenos Aires, Argentina), Madres de Plaza de Mayo (Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo), 1983, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Lois Wasserspring 2018.281. Courtesy of the artist's estate.

In the early 1980s, Argentine photographer Alicia D’Amico began documenting the protests of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a human rights movement launched by women who had lost sons and daughters to the brutal military regime that controlled Argentina from 1976 until 1983. In this shot, three of the Madres stand beneath an obelisk that commemorates the May Revolution that launched national independence. To the left is Renée Epelbaum, one of the leaders of the movement, whose three children disappeared after being kidnapped in 1976.

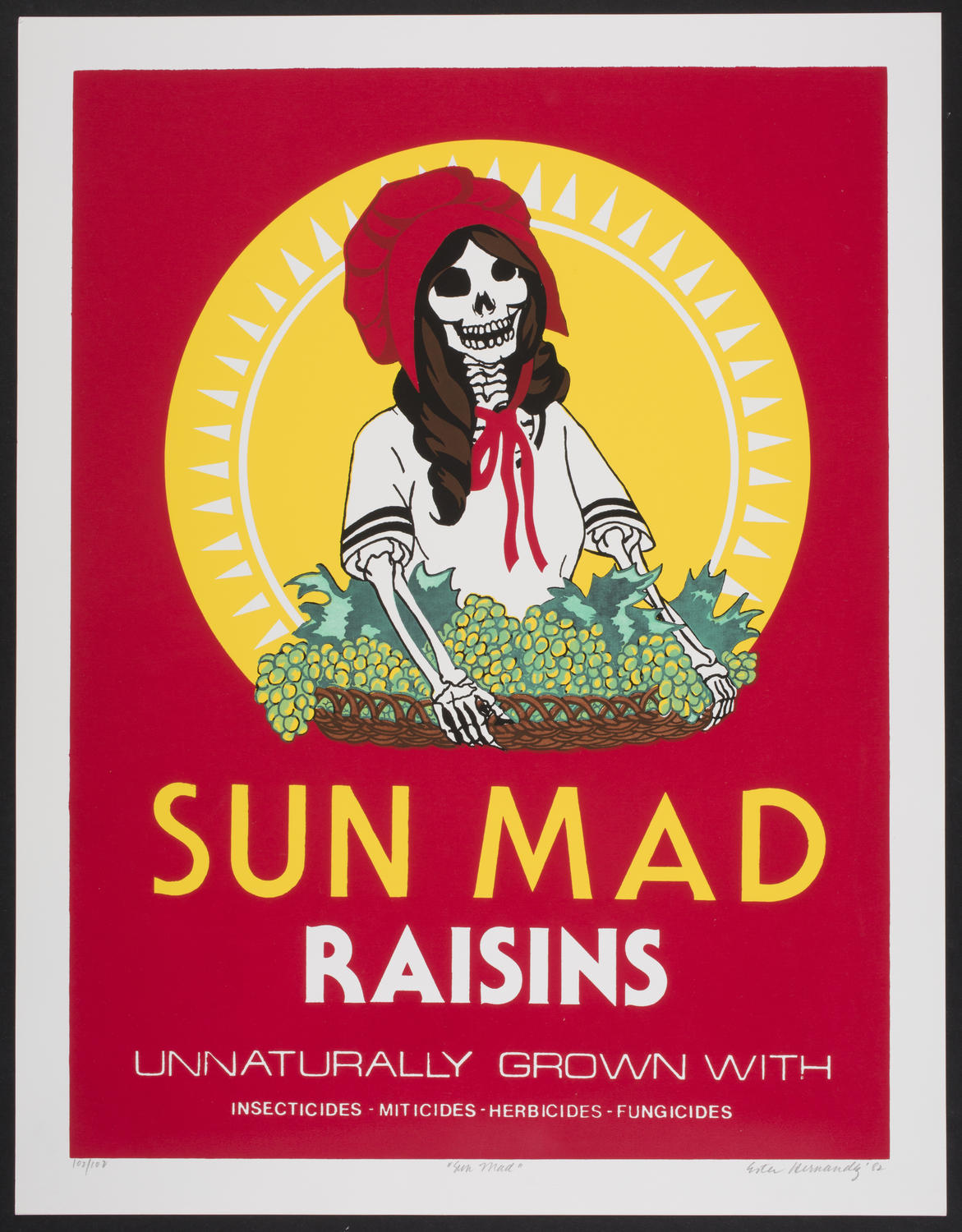

Ester Hernández (b. 1944 Dinuba, California), Sun Mad, 1982, Screenprint, Museum purchase, The Nancy Gray Sherrill, Class of 1954, Collection Acquisition Fund 2017.170. Courtesy of the artist.

Ester Hernández grew up in the San Joaquin Valley in California, the daughter of increasingly politicized agricultural laborers. In this poster, she transforms Sun-Maid’s charming maiden into a skeleton poisoned by pesticides. As she later recalled, “Sun Mad evolved out of my anger and my fear of what would happen to my family, my community, and to myself.” The image also exposes the gender mythologies invested in the corporate logo. In real life, women do not so cheerfully carry heavy trays of fruit against their chests during the harvest.

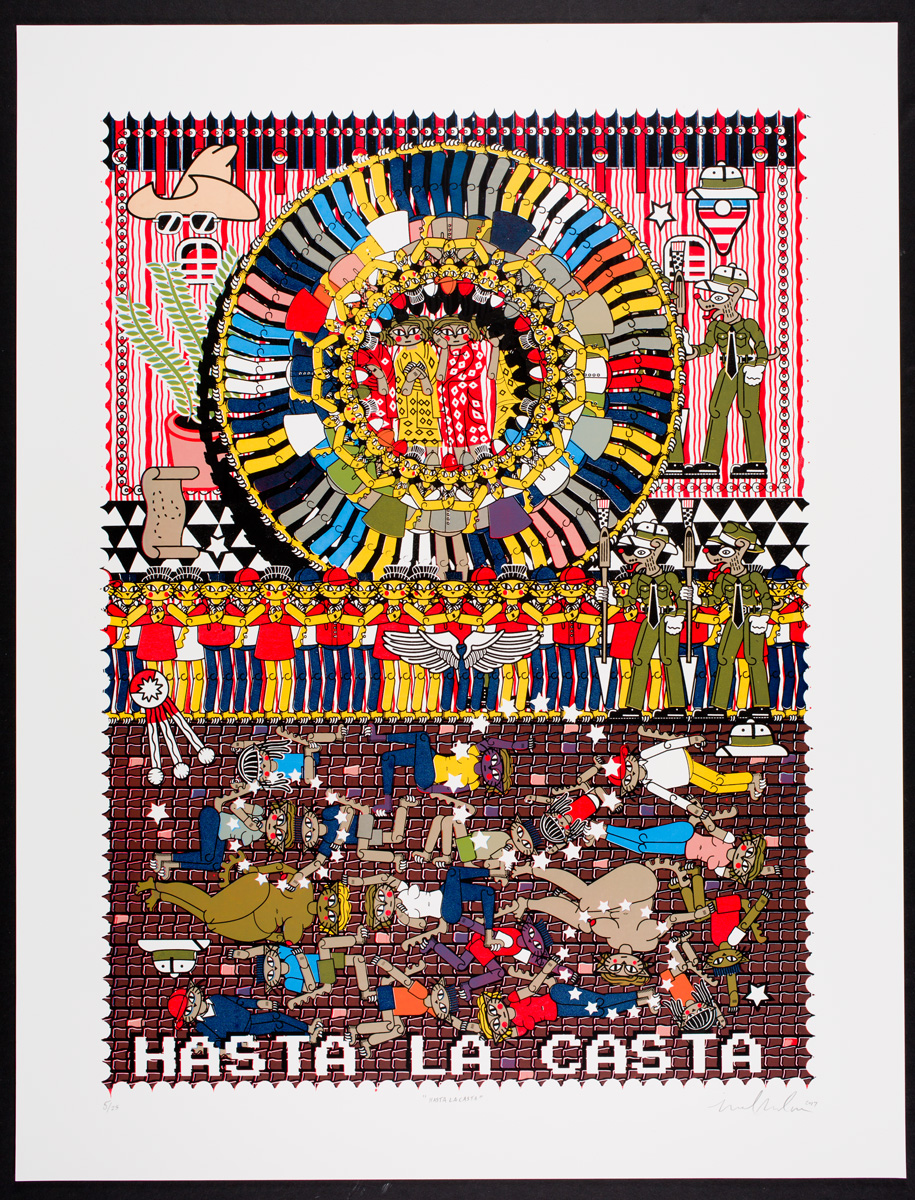

Michael Menchaca (b. 1985 San Antonio, Texas), Hasta la Casta, 2017, Screenprint, Museum purchase, The Nancy Gray Sherrill, Class of 1954, Collection Acquisition Fund 2018.5. Courtesy of the artist.

The youngest artist in the exhibition, Michael Menchaca graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2015. His prints combine elements taken from pre-Columbian manuscripts with digitally-generated cartoons, to form dense, patterned compositions that refer to endlessly repeated crimes against immigrants and minorities. Hasta la Casta alludes to the current targeting of undocumented citizens by ICE: the title collapses Dirty Harry’s violent appropriation of the Spanish phrase “Hasta la vista” and the lingering racism of the colonial caste (or casta) system.