Free and open to all from Tuesday to Sunday 11 AM to 5 PM. The Davis is closed on Mondays and holidays.

War and Loss

Over the past century, artists in Latin America have dealt with conflicts of every dimension. The Mexican Revolution of 1910–20 fractured the nation, though Emiliano Zapata emerged as a shared symbol of the demand for change. During World War II, artists sought to rally support for the anti-fascist struggle or reveal the anxiety and confusion common to every war. For artists living in the US, the military onslaughts in Vietnam and later the Middle East were equally impossible to ignore. Photojournalists seem to have been present at every bloody moment, from Bolivia to Nicaragua. The invariable result of so much fighting is loss, whether symbolized by the coffins of average citizens or the murder of an anonymous protesting worker.

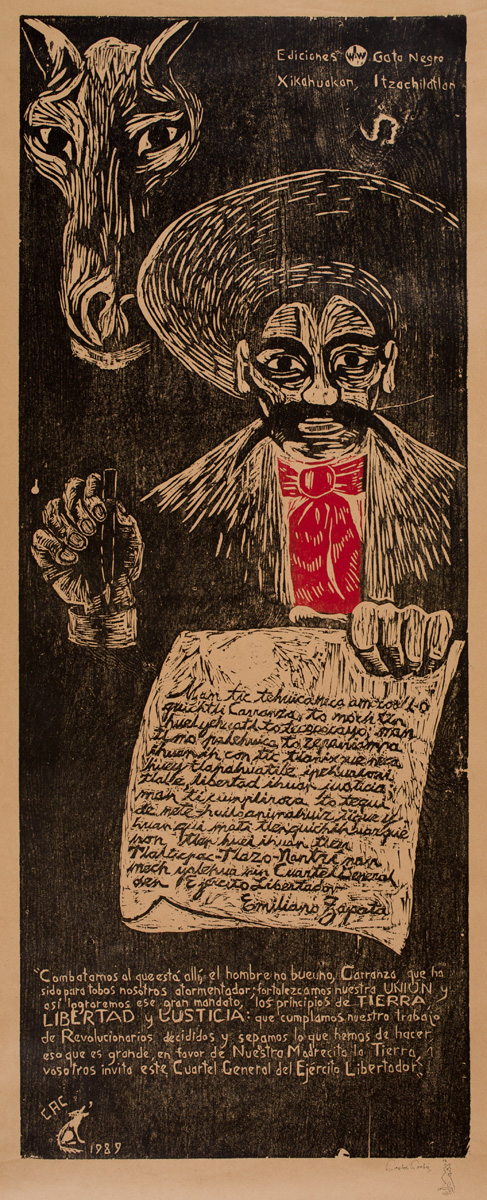

Carlos Cortez (Milwaukee, Wisconsin 1923 – 2005 Chicago, Illinois), Zapata—Liberty and Justice, 1989, Woodcut, Museum purchase, Erna Bottigheimer Sands (Class of 1929) Art Acquisition Fund 2003.59

Few heroes have been more widely represented in visual terms than Emiliano Zapata, a champion of land reform during the Mexican Revolution (1910-20). Decades later, Zapata was embraced by the Chicano civil rights movement. In the enormous woodcut by Carlos Cortez, Zapata holds a 1918 manifesto, written in the indigenous language Nahuatl, which calls for the defeat of bad government and the defense of “the principles of land, liberty, and justice.” A Spanish translation appears below it. Cortez embraced revolutionary politics: he was a member of the radical Industrial Workers of the World.

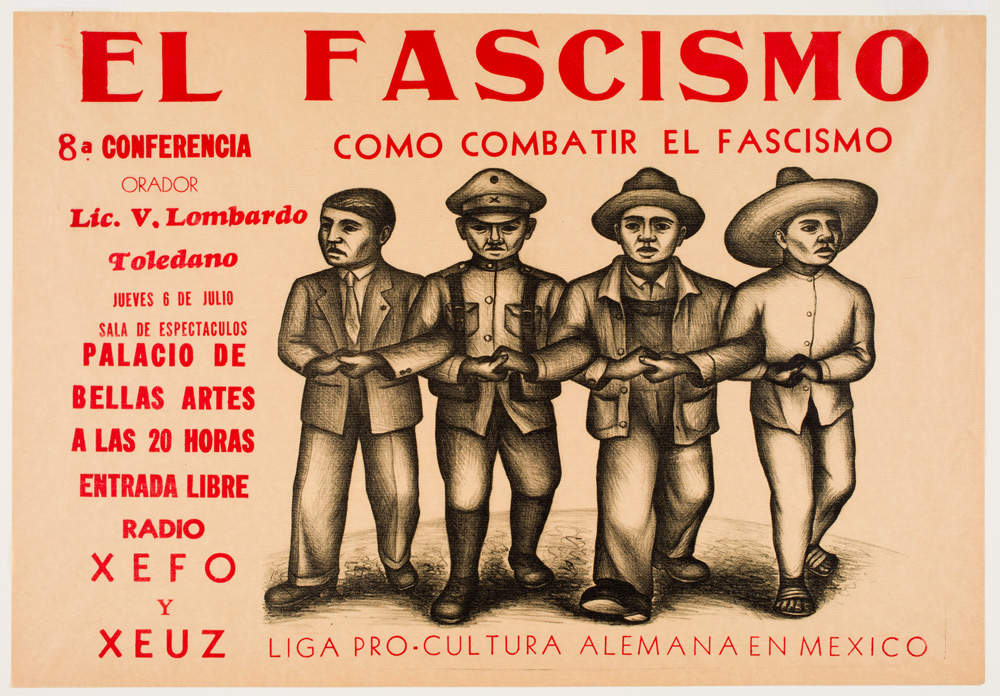

Jesús Escobedo (Santa Clara del Cobre, Mexico 1918 – 1978 Mexico City, Mexico), El fascismo: 8a conferencia, Cómo combatir el fascismo (Fascism: 8th Lecture, How to Combat Fascism), 1939, Lithograph, Museum purchase, The Dorothy Johnston Towne (Class of 1923) Fund 2002.76

A group of radical artists founded the Taller de Gráfica Popular (Workshop of Popular Graphics or TGP) in Mexico City in 1937 as a collective space dedicated to the production of didactic prints and posters for widespread distribution. In its early years, the TGP focused largely on international threats, and particularly on the spread of fascism. This poster advocates unity of the Mexican worker, farmer, soldier, and bureaucrat in support of the antifascist cause.

Sergio González-Tornero (b. 1927 Santiago, Chile), Peace on Earth, 1970, Deep etching and relief, The Nancy Gray Sherrill, Class of 1954, Collection 2009.504. Courtesy of the artist's estate.

Chilean-born Sergio González-Tornero studied in Paris at Stanley William Hayter’s renowned printmaking studio, Atelier 17. His concerns about US involvement in Vietnam led to this singular antiwar image, ironically titled Peace on Earth. The image of a threatening bomber testifies to powerful forces, creative in the engraver’s studio but destructive on the battlefield. At age 91, González Tornero remembered it as the sort of thing an artist did “to make him feel better” about the conflict, a modest assertion that takes nothing from the work’s frightening impact today.

Enrique Chagoya (b. 1953 Mexico City, Mexico), The Ghost of Liberty, 2004, Color lithograph and chine collé, Museum purchase, The Nancy Gray Sherrill, Class of 1954, Collection Acquisition Fund 2004.94. Courtesy of the artist; published by Shark's Ink, Lyon, CO.

Enrique Chagoya’s The Ghost of Liberty appropriates the screenfold format of Aztec and Maya manuscripts, made before and after the Conquest; it was printed on amate or bark paper, similar to that used by indigenous artists. Created after the United States invasion of Iraq, the book features an incongruous cast of characters culled from comic books and newspapers: the Lone Ranger and Tarzan, Buddha and Quetzalcoatl, and a mesmerized George W. Bush staring at a light bulb.