The Davis Museum is closed for Wellesley College’s winter break. Please join us at our spring opening celebration on February 5, 2026, at 4 pm.

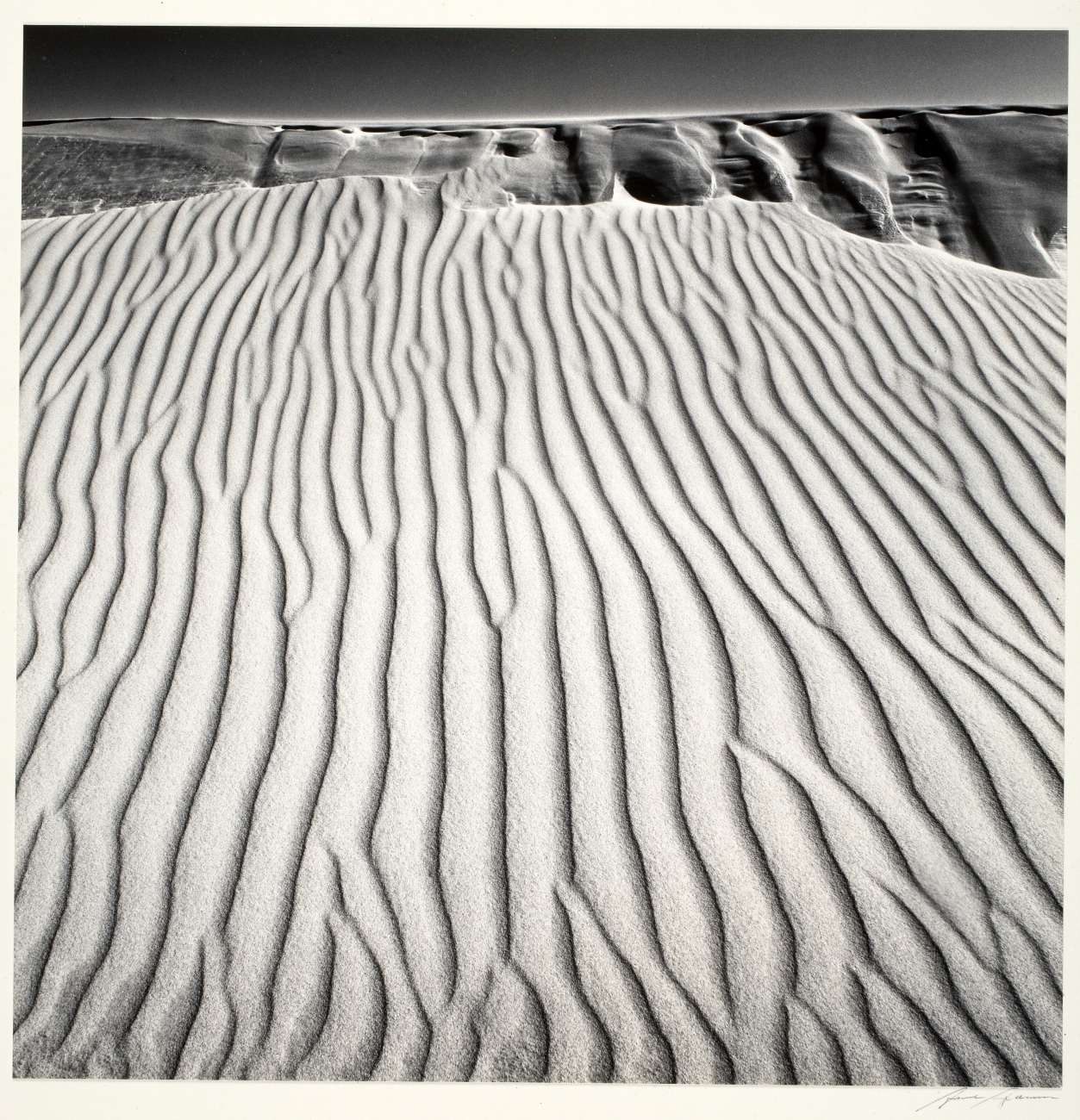

Dunes, Oceano, California

Gelatin silver print, 10 1/8 in. x 10 1/16 in.; mount: 18 in. x 12 1/2 in.

Bequest of Mrs. Toivo Laminan (Margaret Chamberlin, Class of 1929)

1979.93

As a child growing up in San Francisco, Ansel Adams often spent time exploring the dunes and beaches of the Golden Gate’s wilderness. This early contact with the region’s landscapes, which would eventually become overrun with commercial and industrial developments, no doubt informed his most famous photographic subjects. He later wrote, “I constantly return to the elements of nature that surrounded me in my childhood… more than seventy years later I can visualize certain photographs I might make today as equivalents of those early experiences.” Today, the photographer’s highly detailed images of dramatic valleys and rugged terrains express nostalgia for the formerly undiminished beauty of an ideal nation.

Born in 1902 at the height of the Progressive movement, Adams held the reform-minded outlook that would define his position as one of the leading exponents of environmental protection. Over the course of his lifetime, he attended countless meetings and wrote letters to bureaucrats in support of conservation causes. His most lasting contributions, though, were iconic photographs that came to define notable natural sites and drew attention to the importance of their preservation. An avid outdoorsman, Adams revered the natural world; he believed that the precisionist realism offered by photography was best suited to represent it. In 1932, he and ten other photographers formed the group f/64, named for the smallest aperture available on lenses at that time. The group, whose members included Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham, called for a new direction in photography that favored the sharply detailed images with great depth of focus achievable by a smaller aperture. This approach broke with Pictorialism’s preference for romantic and soft-focus techniques, which Adams saw as an attempt to emulate painting, the traditional form of fine art. “Straight” photography, he believed, was more true to the medium’s directness, and deserved recognition in its own right.

Ansel Adams’ legendary technical mastery—which enabled him to depict the transient effects of light and atmosphere—is on display in Dunes, Oceano, California. Desert landscapes were among his primary subjects, but also among the most difficult to photograph. “The desert experience is primarily one of light; heroic, sunlit desolation and sharp, intense shadows are the basic characteristics of the scene,” he wrote. Though the image’s first impression is one of vast emptiness, the stark simplicity of this natural occurrence is precisely what imbues it with great majesty. The camera’s perspective, which allows the full scene to open up to the eye rather than immediately presenting itself, endows it with a sense of awe and grandeur. Ridges in the sand divide innumerable particles of sand into an intricate network of shaded grooves that create a pulsating visual rhythm as they draw our gaze toward the horizon. The precision of the resulting maze emphasizes nature’s ability to resolve order out of chaos, and draws attention to the photographer’s creative intuition in selecting and framing the image.

Emily Zhao ‘17

Curatorial Intern, Summer 2015