The Davis Museum is closed for Wellesley College’s winter break. Please join us at our spring opening celebration on February 5, 2026, at 4 pm.

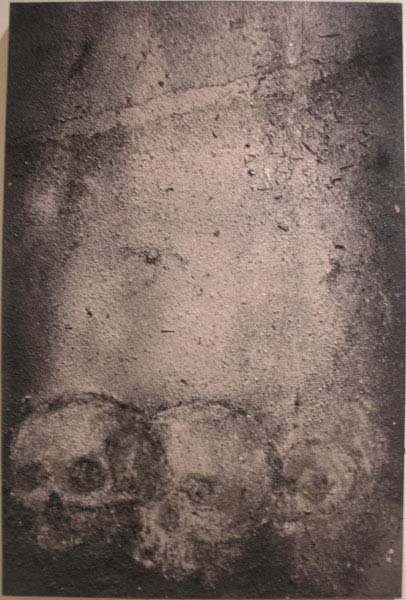

Ash Skull No. 19

Zhang Huan, Ash Skull No. 19, 2007. Ash on linen, 59 in. x 38 3/8 in. (149.9 cm x 97.5 cm). Partial gift of Milly and Arne Glimcher (Mildred L. Cooper, Class of 1961) and museum purchase, Lee and Lawrence Ramer (Ina Lee Brown, Class of 1956). 2009.54

In 2007, Chinese contemporary artist, Zhang Huan (b. 1965) moved back to China after living in the United States for seven years. Upon his return, he visited the Longhua Temple in Shanghai to burn incense before Buddha. It was here that Huan found the material that would inspire the next phase of his work. The ash, which fell from a large incense burner and covered the floor of the temple, took on great meaning for the artist. Traditionally, burning incense is the means by which the Chinese commune with their ancestors and other deities. The ash is what remains of this spiritual practice, of the mediation between human and otherworldly beings, between daily life and the spiritual realm. Beyond this, ash also has medicinal properties: it carries the power to heal. As Huan has said, ash, though insubstantial, “is a short-lived witness to human spirituality” that carries “unseen sedimentary residue, and tremendous human data about the collective and individual subconscious.” When the artist learned that the ash from this and other temples, traditionally scattered in seas or lakes, deposited in woods, or buried, was being processed as garbage, he began to gather the ash as a material for his work in both painting and sculpture.

Huan’s return to China and the commencement of his ash series represented a move away from the powerful performance art that characterized his earlier work and toward experimentation in object-based media. Nonetheless, many of the same themes are at play in this later body of work. The canvas, rather than the body, becomes the site where struggles between the individual and the collective, history and memory, identity and spirituality occur. Huan creates images of historical events, people, and earthly symbols, like the skull found in the Davis Museum’s painting, that are haunted by the spiritual practice and the individual and collective memories carried in the ash that has been used to create them. Huan’s art often deals with the construction of a cultural identity in the face of the Cultural Revolution, which attempted to erase the collective memory of the Chinese people and has caused a generation to suffer as a result of the disjunction that exists between personal memory and official record. By creating singular images, like the skull, from thousands of individual particles of ash, he attempts to restore spiritual and emotional life, as well as an individual and collective memory to this generation. The blurred contours and illusive forms of the work fight against the notion of a singular accepted history, at the same time that they celebrate the fragmented, yet united, memory of a people.

The fragile, volatile medium of ash, whose appearance is subject to change over time, also suggests the lack of a stable, homogenous identity. Ash, in a certain sense, celebrates this living, changing memory. The ash Huan utilizes is living, not dead. The skull, which is a recurring motif in Huan’s work, also suggests life for Buddhists believe there is no finality in death—one is continually reborn. Thus, Huan’s skull pieces, some of which are titled “Renaissance,” symbolize rebirth. Like a Phoenix rising from the ash, the past may be reborn in these haunting images.

Sophie Kerwin ‘16

Summer Curatorial Intern 2014