/ How Sexual Assault Built America

Subscribe

/ How Sexual Assault Built America

Subscribe

"I consider a woman who brings a child every two years as more profitable than the best man of the farm. What she produces is an addition to the capital, while his labors disappear in mere consumption."

--Thomas Jefferson, 1820

About a half-mile from the Maplewood Farm, where Margaret Garner was enslaved, the Triple Crown subdivision is growing. It spans acres, with a golf course and a country club ribboning through; the subset communities, with fluting names like Cantering Hills, Steeplechase, and Sir Barton Place, nod dozily to the thoroughbred pastimes of Kentucky. The streets are lined with GMCs and CR-Vs and white three-rail ranch fencing. The houses, withelaborate brick fronts and boxy vinyl backs, cluster together. Neighborhood by expanding neighborhood, the landscape fills with aspiration—an American through-line to the centuries in which enslaved people worked the farms of these hills for the material progress of Kentucky and its slaveholders.

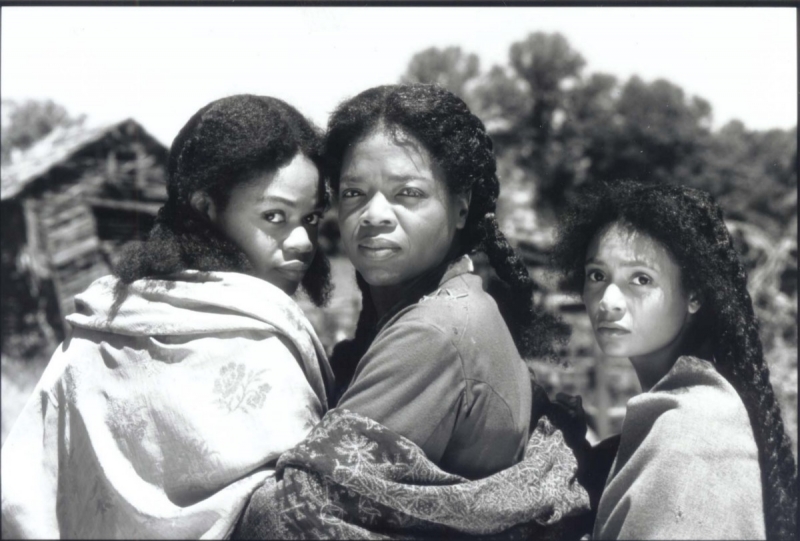

I am here because I am working, with the generous help of long-laboring historians, literary critics, and the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, to coordinate a more thorough memorialization of the journey of Margaret Garner, the enslaved woman who inspired Toni Morrison’s Beloved. My hope is that it will encourage visitors to travel the landscapes where Garner lived, worked, escaped, killed, and stood trial (one of the longest Fugitive Slave Trials in American history), thereby connecting those landscapes, and what happened in them, to present American realities. Last night, I attended a lecture at the Freedom Center by Dr. Nikki M. Taylor, the first black woman to write a book-length history of Garner (Morrison, of course, paid tribute to her in fiction). There are still fewer books about Garner than there should be; Taylor’s new, seminal text, Driven Toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio, uses interdisciplinary approaches to reconstruct the life of a woman who, despite her historical significance, was and is largely undocumented. Dr. Kristine Yohe, of Northern Kentucky University, is my docent today; NKU and a Maplewood neighbor named Ruth Brunings are the only folks with touring access to the privately-owned Maplewood Farm, and the cookhouse where Garner once labored.

Garner had four children here at Maplewood, and was pregnant with her fifth when she and her family escaped on a sloe, freezing night in early 1856. But motherhood was fraught for her, as it was for all enslaved women: Even when an enslaved woman had consensual sex, she had no autonomy to protect the children that might result from it. She was allowed neither the security nor the intimacy of unthreatened familial bonds. If she married, she had no control over when, where, or how often she could see her husband, who might live on another property (as Garner’s did). She was not designated time to care for her offspring. Her breast milk, the fruit of her maternal body, was often stolen from her children and given to the children of her captor. She never knew when her partner or children might be humiliated, burned, beaten, sold, or killed.

And thus, though we only have a third-hand account that Garner was raped here at Maplewood, I posit that, given these circumstances, we know she was reproductively assaulted.

I want to name and recognize reproductive assault as a subset of sexual assault. It includes rape and forced mating, both of which enslaved women survived at the hands of their captors. But it should also include, among other things, the commodification of consensual sex among enslaved people, resulting in the kidnapping of their offspring--children considered "capital" by our nation's founders. According to Thomas Jefferson, this capital was king, the most valuable of its kind. If we come to understand that reproductive assault includes harvesting black children— children Jefferson perversely called "capital"—then we come to understand that every enslaved American woman who ever gave birth was reproductively, and thus sexually, assaulted—and that according to Thomas Jefferson, this sexual assault was a key driver of the 19th-century American economy.

As a continuation and an amplification of the #metoo movement, we’ve seen the crucial beginnings of #hertoo, which emphasizes the need to support marginalized women and girls internationally and domestically. I would also call for #foremotherstoo, which would reexamine American national foundations to understand how our country gained much of its wealth through the wombs of enslaved and oppressed girls and women. Just as Jill Abramson’s article “Do You Believe Her Now?” calls us to revise our understanding of recent history and its leaders in light of #metoo revelations, so can the same revelations instigate a revised, long-reaching historical comprehension that better tells the realities—sometimes atrocious—that built America.

Margaret Garner’s reproductive assault helped make her assailants wealthy and renowned. It boosted the agricultural business of Kentucky and even, arguably, the territorial expansion of America: Garner’s first owner, John Pollard Gaines, became the first governor of Oregon Territory. Heading West, John Pollard “practically gave” (Taylor 29-30) his brother Archibald the Maplewood farm,

which meant he “gave” Margaret to Archibald, too; we see here the effects of unearned white privilege and the legacy of familial favor, as well as the failure of any claim about slavery’s economic necessity (if John Pollard could stand to gain so little from the sale of Maplewood, he might as easily have chosen to “give” his captives their freedom).

which meant he “gave” Margaret to Archibald, too; we see here the effects of unearned white privilege and the legacy of familial favor, as well as the failure of any claim about slavery’s economic necessity (if John Pollard could stand to gain so little from the sale of Maplewood, he might as easily have chosen to “give” his captives their freedom).

The Gaines family—Dickensianly named—still owned Maplewood 20 years ago, according to Ruth Brunings, whom I briefly interviewed on March 1, 2018. (A subsequent interview with Brunings on April 15, 2018, one month after the initial publication of this essay, provided documentation that the Gaines ancestors sold the farm in 1994, twenty-four years ago. It also showed that the Gaines family sold the farm in 1884 but re-bought it in 1913). She told me that the Gaines descendant who sold the farm never lived there; this shows the reach of privilege, which can enrich beyond culpability, or even, sometimes, consciousness. (There is, however, some recognition at Maplewood: displayed at the privately-owned cookhouse is a card from John Pollard’s great-great-great grandson; it bears the Gaines family crest and offers to discuss “Gaines/Garner History.”) The value of Maplewood’s land once depended on the number of enslaved black people who worked it. Their reproduction—forced and not—enriched the Gaineses. This effect of capital-building was more complex than the simple fact that more slaves were worth more money. More slaves also made the land yield more; more yield allowed more investment; more investment meant a greater cushion of wealth, which enabled the family to keep the land even after slavery was abolished. In the case of the Gaines family (if one subtracts the years between 1884 and 1913, when the Gaineses sold and rebought the land), Maplewood accrued value for a century after the Civil War. Thus the wealth reaped by the Gaines family from the womb of Margaret Garner, and the bodies of other enslaved people, perpetuated late into the 20th century. I mention this not to vilify the Gaines descendants, but to follow one continuous effect of slavery and reproductive assault into contemporary times (and to exemplify and support the logic of larger-scale reparations).

It was 19th-century feminist Lucy Stone who claimed in court that Garner was raped. As I stated before, and as is the case with so many Americans who were legally barred from the status of personhood, we have no first-person record of her treatment. However, we know that Archibald Gaines reproductively assaulted her at least once more when, legitimized in his terrorism by the Fugitive Slave Act, he attempted to kidnap her children from their hours-old freedom in Ohio. We know that, when Reverend Horace Bushnell visited her, she said of that assault: “Hope fled...”

When Garner realized she could no longer offer her children any other escape from the assault of slavery, she tried to spare them by trying to kill them—by sending them, as quoted by Bushnell, “home to God.” She succeeded in killing her toddler, Mary.

For Garner, a dead daughter. For Gaines, a dead harvest.

Now, at the gate of Maplewood Farm, a historical plaque memorializes the fame of John Pollard Gaines, but makes no mention of slavery, nor Margaret Garner, nor the way Gaines’s family brutalized her.

Back near Triple Crown, at the church where Garner’s family gathered to run in 1856, a Subaru loaded with a mother and her children corners the intersection at Richwood Road. It’s going too fast, a little, and disquiets the church cemetery. The pastoral fills with more noise as road work starts again, post-lunch; across the street, atop a mossy hill, a reproduction of a Tara-ish mansion, with fat pillars, is cast in shadow by an airplane departing the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky airport. The cars, the construction, the street names, and the golf course speak to an American aspiration, and a willingness to forget, that has not died since the time of Archibald Gaines. “New development!” cries a Drees Homes sign from the side of Route 338. Hope flees, sometimes, but American hunger for material progress never seems to.

In Covington, Kentucky, where the Garners crossed the river for Ohio, a historical marker tells part of their family story. But nowhere here—not in the children’s section of the Richwood Presbyterian graveyard, where 19th-century tombstones small as splayed hands dot the green expanse, nor beside Maplewood’s memorial for John Pollard Gaines—is any public sign of the black women, men, and children who, unconsenting, made this land rich.

Further Reading:

Frederickson, Mary E., and Delores M. Walters, eds. Gendered Resistance: Women, Slavery, and the Legacy of Margaret Garner. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Taylor, Nikki M. Driven Toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2016.

Reinhardt, Mark. Who Speaks for Margaret Garner? The True Story that Inspired Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Photo Credit (banner): Harpo Films/Clinica Estetico/Touchstone Pictures, via "Beloved" movie.

Photo Credit (in text): Mical Darley-Emerson, “Maplewood.”