/ The Migrant Crisis in Palermo, Italy

Subscribe

/ The Migrant Crisis in Palermo, Italy

Subscribe

I walked through a labyrinth of cracked sidewalks and the putrid smell of rotting flesh. I pondered on how it would be even possible for me to explain the imaginable poverty and violence that masked this forgotten part of Italy to people like me who were often fed images of a very different side of Italy. I had traveled 3 hours to Agrigento, a city in the southernmost part of Sicily, where 12 migrants had drowned in the Mediterranean Sea.

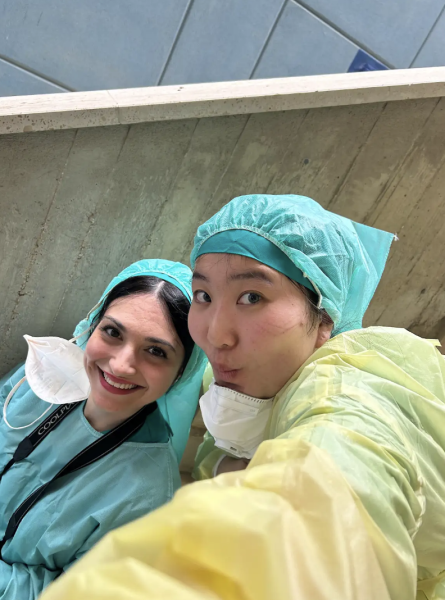

I received a rigorous STEM education from Wellesley that had prepared me well, but in a way, I was extremely privileged. The sheep brain and pig dissections in my introductory neuroscience and biology courses were stimulating but were already neatly prepared in formalin. The white, clean rooms were air-conditioned, and we were allowed to sit while tranquilly dissecting organs. These were things I had taken for granted. In Agrigento, we were taken to a basement in a small room crowded with giant coffins. I had never seen a coffin in my life before, much less a corpse. The smell was so strongly rancid that even wearing two masks was no use. With the team of doctors and medical residents, I collected any identifiable information such as descriptions of clothing, dental anomalies, and basic metrics such as height along with photographic evidence. I didn’t know these people, but I was holding back tears as I felt a lump form in my throat as I took photos of their bloody, swollen limbs. They had been in the sea for so long that they no longer had faces that had been corroded over time by the salty, unforgiving water.

It had been my dream since I was 14 to work on the migrant crisis in Italy. My mother was an immigrant in Italy in the 1990s where she worked tirelessly to send money to her family located in a small, rural village in Northern China. I had read news articles detailing each traumatic shipwreck, but this crisis was presented right in front of me, and it was something beyond fathomable. I knew that some would view these victims as simply corpses or numbers added to the list of mortalities but to me, they were someone’s brother or perhaps their mother so desperate that they were willing to risk their lives to leave their home.

I continued my internship working at the “Paolo Giaccone” Hospital in Palermo where I assisted in conducting psychological and medical forensic interviews for migrants with organizations like Doctors Without Borders, but I could never forget about those 12 people I had seen. Many migrants coming from sub-Saharan Africa must pass through Libya to reach Italy. In Libya, migrants are sent to illegal and government-funded prisons where they are subjected to immense torture and forced into prostitution. I was writing reports detailing the types of torture they faced which was later sent to a court that decided whether asylum was granted. I squeezed the hands of a woman who detailed giving birth on the boat from Libya to Sicily. Her baby did not survive and out of desperation, she put her baby in a bread bag until she could seek a proper burial on the island. I saw grown men uncontrollably tremor as they recounted having every ounce of dignity beaten out of them in illegal Libyan prisons while also facing sexual abuse.

My work did not only pertain to migrants in Italy but also citizens of Palermo. I analyzed the organs of a 90-year-old Sicilian man who had been a victim of elder abuse after his death. I saw the many children who died from unimaginable pain like car crashes brought on by alcohol, child abuse, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) which were fueled by the raging poverty and limited access to education. The work my team and I did was critical to seeking justice for these vulnerable people, making this the most profound, meaningful experience of my life.

Regardless, the shock of witnessing the underbelly of human suffering hit me like a truck going 100 miles per hour. I felt powerless seeing the modern-day slavery employed right in front of my eyes by the Mafia: Migrants forced into carrying heavy bags full of various items like sunglasses, necklaces, and floaties in 100-degree weather barefoot in the burning sand as rich tourists from around the world lounged on the beaches in oblivion. From judges to children, no one was safe from mafioso.

My experience in Palermo had a profound impact on not only my future career but internally as well. I saw the worst of humanity, but I also saw the best of it too. I met the most dedicated staff who influenced me to lead with a great sense of maturity and courage. Most of all, I learned to lead my life with gratitude knowing that the love, care, and empathy for humanity always triumphs over corruption and greed.