/ Peace is War

Subscribe

/ Peace is War

Subscribe

“Don’t feed the trolls,” they say. It is common advice for our current politics, whether it is on social media or in person. To some extent, this advice makes sense: a troll specifically refuses rhetorical stasis in order to make rational debate impossible. To paraphrase Chaucer’s Harry Bailly, the tavern-keeper who “governs” the tale-telling contest on the road to Canterbury, why play a game with an angry man?

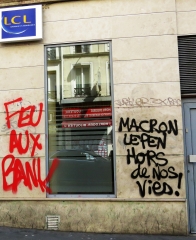

However, in Trump’s America, the troll feeds you. By this I mean that our current political culture lives on trolling, not just in its margins, whether frog-inhabited swamps of right-wing reddit or semi-public Facebook pages of our unwoke uncles: for liberal, educated, “rational” America, trolling feeds powerful affects of superiority, and those affects help ground what I see as a dangerous dedication to the value of stasis, of peace both rhetorical and political, that is in fact a tool of repression.

Peace is usually one of those political values that provoke little public opposition. We are encouraged to “give it a chance” because the alternative to peace is war, either organized military warfare, or social conflict. However, as an academic medievalist, I’m suspicious of peace. Peace is often an enforced good in medieval discourse.

Medieval scholar D.W. Robertson’s description of the medieval political order as “quiet hierarchies” has a particular fantasy appeal for moderns. In the midst of capitalism that thrives on competition and class conflict, the bourgeoisie can nostalgically imagine a hierarchy in which domination was peacefully accepted, the very domination that they took from medieval nobles and ecclesiastics. At the same time, they can look back upon the Middle Ages as a time that was both unfree and unwoke. The fantasy finds it a time before racism, where a homogenously white Europe could be either castigated for its external conflicts with Islam, or imagined as the perfect liberal society, in which a few outsiders can be graciously integrated.

This fantasy of a peaceful yet still hierarchical world continues to dominate, perniciously, liberal politics. Where I’ve seen it most is in the distaste for protest that has developed not simply on the now ascendant right (who seemed to find protest, even armed protest, remarkably American not so long ago), but on the liberal left, where the “violent attack” on Charles Murray at Middlebury produced the condescendingly gentle counterpoint to trolling, the “think piece.” It bemoans the youth of today, the tender snowflakes that just can’t emotionally bear opposing viewpoints. The same thing happens every time there is a protest: protest is fine, as long as it is respectful. If there is violence, whether against the police, a CVS, or a university window, the protest is delegitimized. Violence is never the answer. As Charles Blow states in the piece linked, “Once violence springs forth, moral authority dries up.”

However, I argue that our notion of peace is ideological, because we (falsely) oppose it to violence. This makes it impossible for us to properly understand either peace or violence, or to assert a moral value beyond stasis, whether rhetorical or political. If stasis, if peace is our supreme moral value, it is because we take pleasure in its effect, and the primary effect is maintenance of the status quo, which includes our moral superiority. We are rational actors, and they are not. We have the facts. I have found these arguments in the strangest places: the same people who teach Foucault and Althusser are arguing politics like rational choice theorists and empiricists. We are betraying our politics in order to appear superior, and we are enforcing peace and stasis exactly where conflict is needed.

And here I want to return to Harry Bailly of the Canterbury pilgrimage, and his conflict with the Pardoner. The Pardoner is Chaucer’s troll: he undermines the entire rhetorical structure of the Canterbury contest, delivering what many consider the best tale but threatening the moral mission that justifies the fellowship of their pilgrim society with his revelation of its fiction. The Pardoner particularly trolls Harry, suggesting that his very rule over the contest is invalid, and lewdly offering Harry his false relics to kiss in order to make up for his sin. Harry replies with a threat of violence (I modernize):

I would rather have your balls in my hand

Than relics or a reliquary.

Let’s cut them off – I‘ll help you carry them;

They shall be enshrined in hog shit! (VI. 952-56)

This potential fight is stopped by the Knight, who insists that they give one another the kiss of peace. I am not arguing that Harry should have followed through on his threat. But Harry’s response takes the Pardoner’s threat seriously (he will not “play”; 958), and, in my reading, the Knight’s enforced kiss of peace exposes the real power: the male, heteronormative, and noble monopoly on violence. The Knight reinforces a stasis that prevents debate, where nothing is serious: “as we did before, let us laugh and play” (967). Immediate violence is avoided, but the social world remains exploitative, and hierarchies force others to be quiet.

I argue that solidarity against exploitation and for collaboration are greater social/rhetorical values than peace. While stasis allows for “rational” rhetorical conflict, it limits that conflict to competition, whose end is victory, and whose social value is always secondary to that end. In Trumpian capitalism, where the only value is victory, dedication to the “free” and “peaceful” competition of ideas opens the space for trolls, who desire victory rather than social good or the nobility of dialogue. We should not extend peace or grant our respect to trolls (especially those, who like the Pardoner, profit from exploitation), and we should not ignore them either. Our mission is to model the pleasures of collaboration, to work against the affective structure of moral superiority, and to revolt against the notion that competition is a necessary or natural state of human social existence.

So perhaps we can rethink “feeding the trolls.” The troll, after all, is traditionally lonely and hungry. While it may be that the best response to a troll is a swift kick (or punch), we might first try to advance a way of life that feeds all those hungry for social pleasure. But stasis is not the answer.

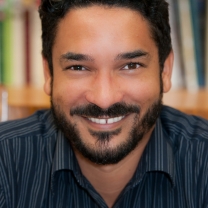

Matthew Irvin is an Associate Professor of English and Chair of Medieval Studies at the University of the South, in Sewanee, TN, where he also serves as the Director of the Sewanee Medieval Colloquium. He researches late medieval English and Latin poetry, and is currently working on a book about pity. He also is proud to be the adviser to the Sewanee Young Democratic Socialists.

Photo Credit: TimOve, "Do you feel LUCKY, punk?," via Flickr, 28 March 2009.