/ Do Facts Matter?

Subscribe

/ Do Facts Matter?

Subscribe

Do facts matter? Of course, because if you consider all the evidence (i.e., the facts) you have a better chance of making wise decisions. But if that is not your goal, and you simply wish to impose your will on others, you will seek to redefine what is meant by “facts” so you justify whatever it is that you’re trying to do. It’s not all that difficult to redefine reality, as we’ve been seeing in the last several weeks. You can claim that “there are no such things as facts anymore,” as Trump surrogate Scottie Nell Hughes recently did, by insisting that reality depends on perception, and perception is subjective. Or, like Trump’s advisor Kellyanne Conway, you can claim that you have access to “alternative facts.”

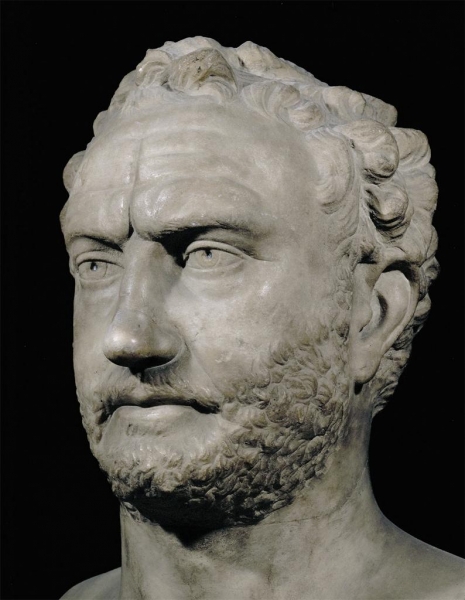

Redefining truth is a means of taking control. The process is vividly described by ancient Athenian historian Thucydides in his history of the Peloponnesian War (430-404 B.C.E.). He not only chronicled the course of the fighting; he tried to understand why people made the decisions that they did, even when their actions flouted traditional ethics and religion. As he describes it, the problem was what he called stasis. That word is often translated as “revolution,” but in context it refers to forming “standings” or what we might now call political parties or factions, small groups of men (women did not count) with common interests.

Some of Thucydides’ observations about the dangers of stasis may help us to understand what is taking place in the U.S.A. today. During the Peloponnesian War, everyone in the Greek world was forced to take sides with either the democratic Athenians or the oligarchic Spartans. To describe what making a choice meant in practice, Thucydides chose to describe the violent infighting between factions in 427 B.C on the island of Corcyra (Corfu) off the northwestern coast of Greece. He understood that what happened in Corcyra could have happened anywhere and would occur again: “so long as human nature (to anthrōpinon) remains the same, these things happen and always will happen, but they can be less violent or different in appearance, as changes in circumstances require.”

He goes on to observe that the factions “changed the usual values assigned to words as a means of justifying their deeds: irrational daring was thought to be courageous loyalty, farsighted reluctance to be a euphemism for cowardice, moderation a cover for unmanliness, and careful consideration of everything to be an inability to act on anything.”

Thucydides understood that the behavior he was describing was neither Athenian nor Spartan, nor Greek, and it seems that he was justified in predicting that people will continue to behave in the same ways. His observations can help us see why in the U.S.A. today the President and his supporters want to change the meaning of words: they are seeking to direct the way we perceive reality, and reorient our moral compass so that wrong will seem right, so that “fact” means “information,” “great” is a euphemism for “terrible,” and what it calls “false” is demonstrably true. As Thucydides observed, the factions “changed the usual values assigned to words as a means of justifying their deeds.”

In Corcyra, Thucydides observes, the pro-Athenian and pro-Spartan factions were so concerned with party allegiance and fighting each other that they did not care about justice or the welfare of their city-state. But he observes pointedly that the citizens who did not join a faction also perished, either because they did not take sides or because they aroused animosity simply by surviving.

In November 1963, at a dark moment in American history, Justice Warren observed: “It has been said that the only thing we learn from history is that we do not learn. But surely we can learn, if we have the will to do so.” We can learn from Thucydides’ account of the conflict in Corcyra that extreme divisions between political parties is a dangerous sign, and that changing the meanings of words is a means both of taking control and justifying illegal and immoral actions. But as Thucydides also makes clear, we won’t be able to save ourselves if we choose not to get involved in the conflict.

Mary Lefkowitz is Mellon Professor in the Humanities, Emerita, at Wellesley College. A scholar of classical antiquity, she is the author and editor of more than ten books, including Women in Greek Myth; Greek Gods, Human Lives: What We Can Learn from Myths; and, most recently, Euripides and the Gods.

Photo Credit: Erich Lessing, via ART RESOURCE.