/ Why We Need Heretics!

Subscribe

/ Why We Need Heretics!

Subscribe

Telling the story of modern philosophy is no simple matter. When precisely is modern philosophy supposed to have begun? Who were the first truly modern thinkers? What was new and modern about their ideas and methods? What does it mean to say that a philosophy is "modern" anyway?

While there is much debate among historiographers of philosophy on how to answer such questions, most agree that something remarkable happened in the seventeenth century. Philosophers in this period showed great (and courageous) intellectual independence as they advanced new ways of looking at the cosmos, at nature and at ourselves. While they differed on many fundamental issues, this highly diverse group of thinkers shared some basic assumptions. They all believed that the older, medieval approach to making sense of the world no longer worked and needed to be replaced by more perspicuous and useful models. They agreed that philosophy should seek explanations of things grounded in the familiar, not the obscure. Above all, they insisted philosophy should proceed not by deference to what ancient authors had to say or what religious authorities demanded, but from the clear and distinct ideas of reason and the evident testimony of experience.

A few years ago, my son Ben and I decided that it would be fun to work together on a project that would both allow me to introduce this period of philosophy to a very broad audience and allow him, fresh out of art school, to get started on his career as an illustrator. Our goal in Heretics! The Wondrous (and Dangerous) Beginnings of Modern Philosophy was to present the philosophers of the seventeenth century in an accessible, engaging and entertaining way. On the one hand, we wanted the book to be a serious introduction based on up-to-date scholarship and to avoid the clichés so often found in textbook histories of philosophy. On the other hand, we wanted our graphic "novel" to be enjoyed by the general, non-academic reader. The biggest challenge, then, was finding the right tone and coming up with a text that is neither academically dense nor condescending and simplistic.

As writer, I tried to be as inclusive as possible. I wanted to go beyond those marquee thinkers who typically constitute the so-called canon of modern philosophy (René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, Bento Spinoza, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, John Locke) and include so-called "minor" figures and women philosophers. Moreover, the distinction between "philosophy" and "science" did not exist in the seventeenth century. Galileo, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton called what they did "natural philosophy"—that is, the philosophy of nature—and so they deserved a prominent place in the story, along with those engaged in more familiar philosophical activities: metaphysics, epistemology, ethics and political philosophy.

I also wanted to make the period come alive for the reader. This meant depicting these philosophers not as isolated individuals each pursuing his or her own vision of things, but as historically embedded people who had to deal with personal, political, and religious challenges. There was also a social dimension to philosophizing in the seventeenth century—as there is today—with thinkers reacting to the ideas of others not only in treatises, but also in correspondence and even in face-to-face meetings. In other words, I wanted this to read as a story or narrative that develops over time and involving characters inhabiting the same social space.

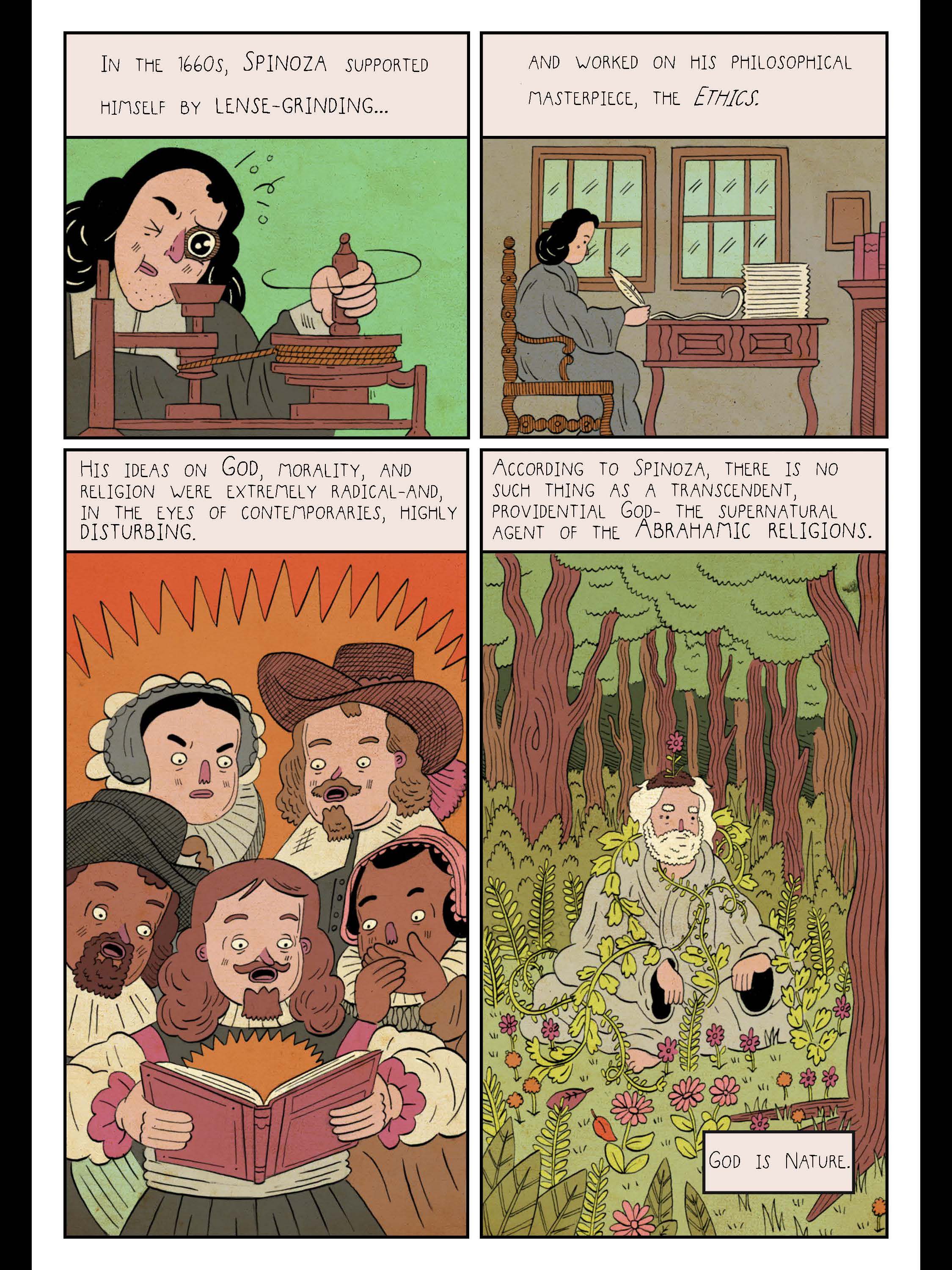

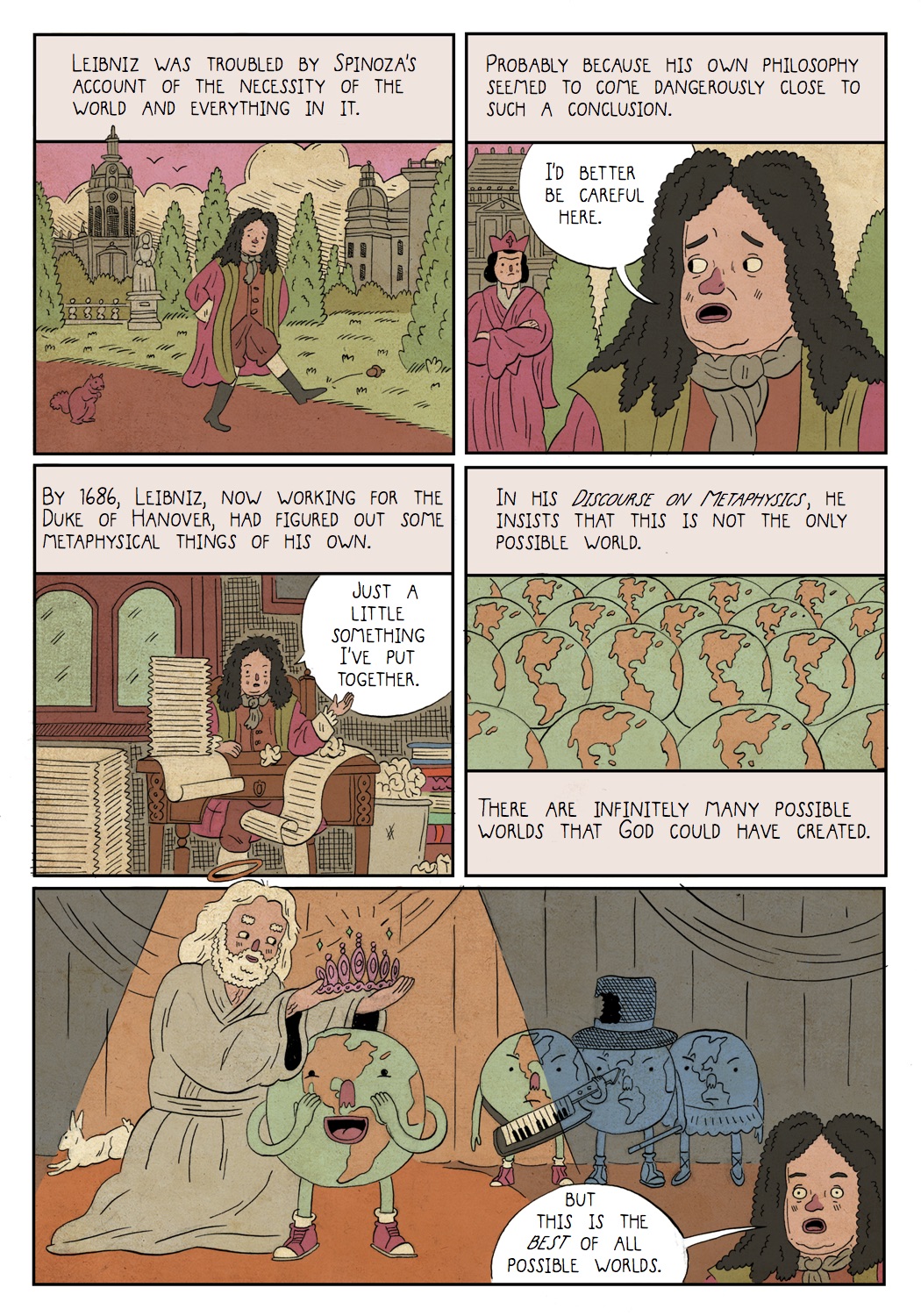

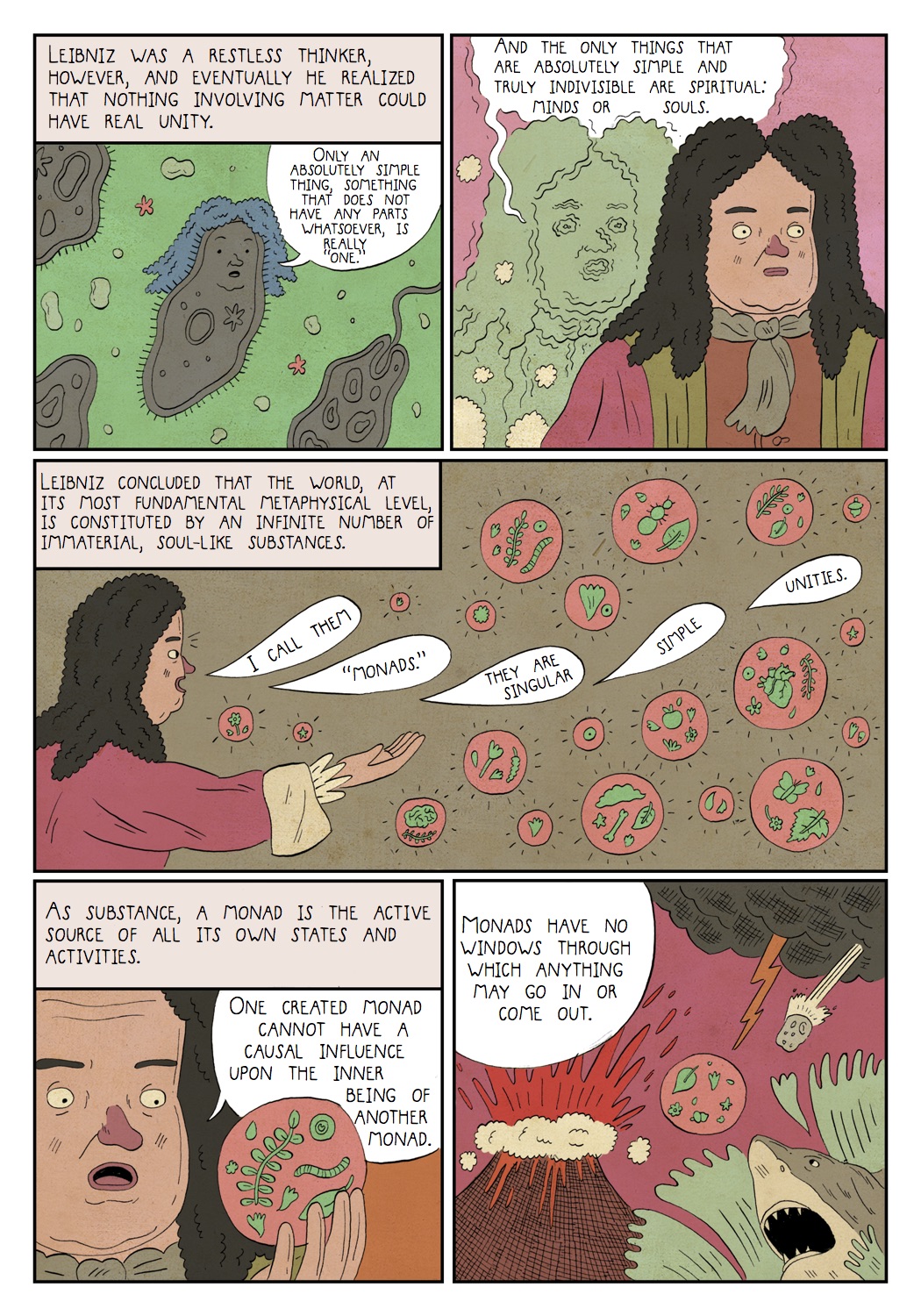

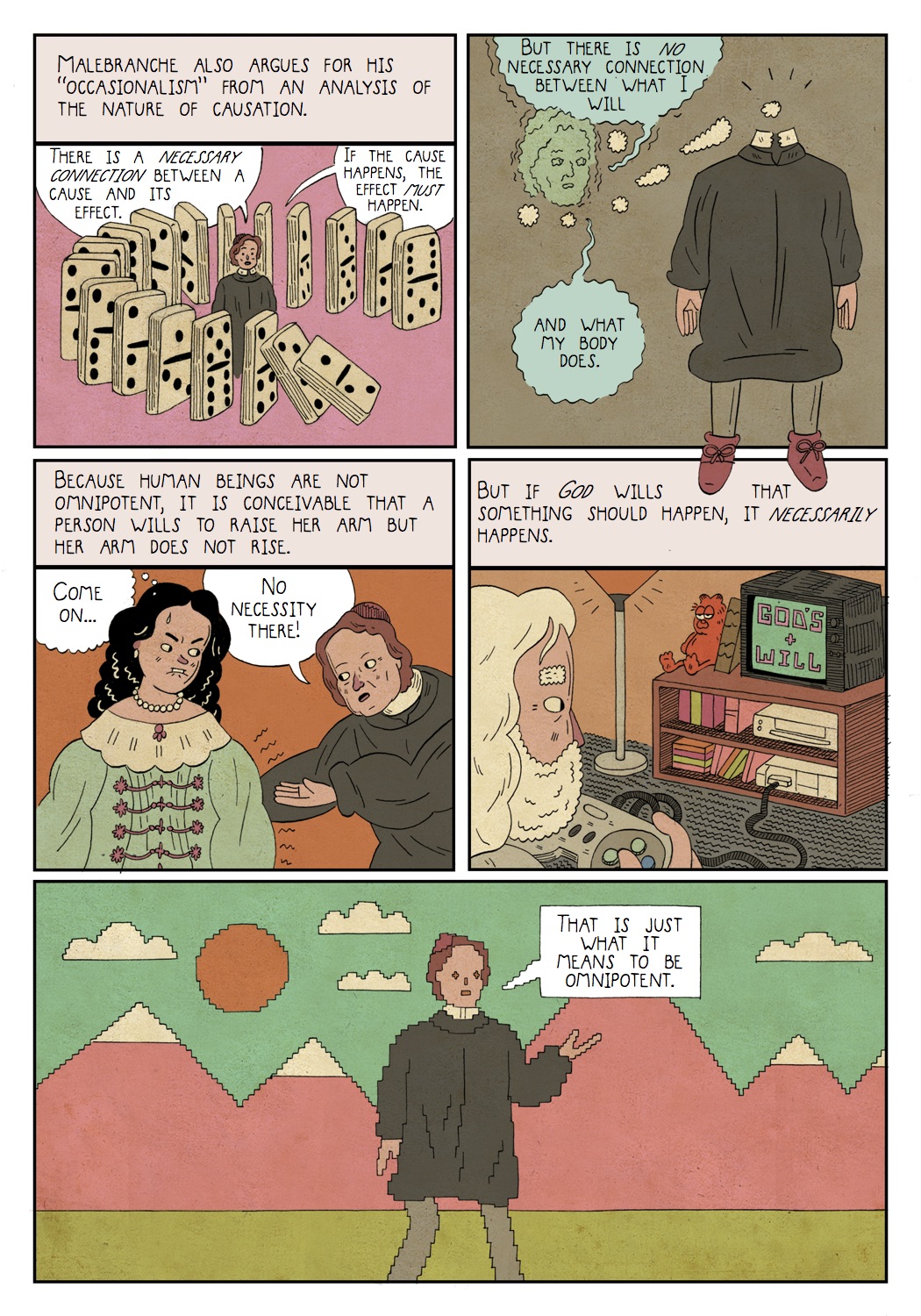

However, it was the illustrator, Ben, who faced the biggest challenges. He had to figure out how to give visual form not only to historically distant (and, to him, unfamiliar) thinkers, but to highly abstract—and very difficult—ideas. How do you illustrate a soul? How do you draw God? What is a "monad" supposed to look like? (A monad is a fundamental item from Leibniz's philosophy that is a kind of spiritual or mind-like "atom". At the most basic metaphysical level, all reality—even bodies—is made up of these "little souls".) More than just the illustrator of my text, Ben is co-author. He helped make the text less academic and more accessible, and he had full freedom to go where his artistic instincts and sense of humor led him (with only the occasional veto from me).

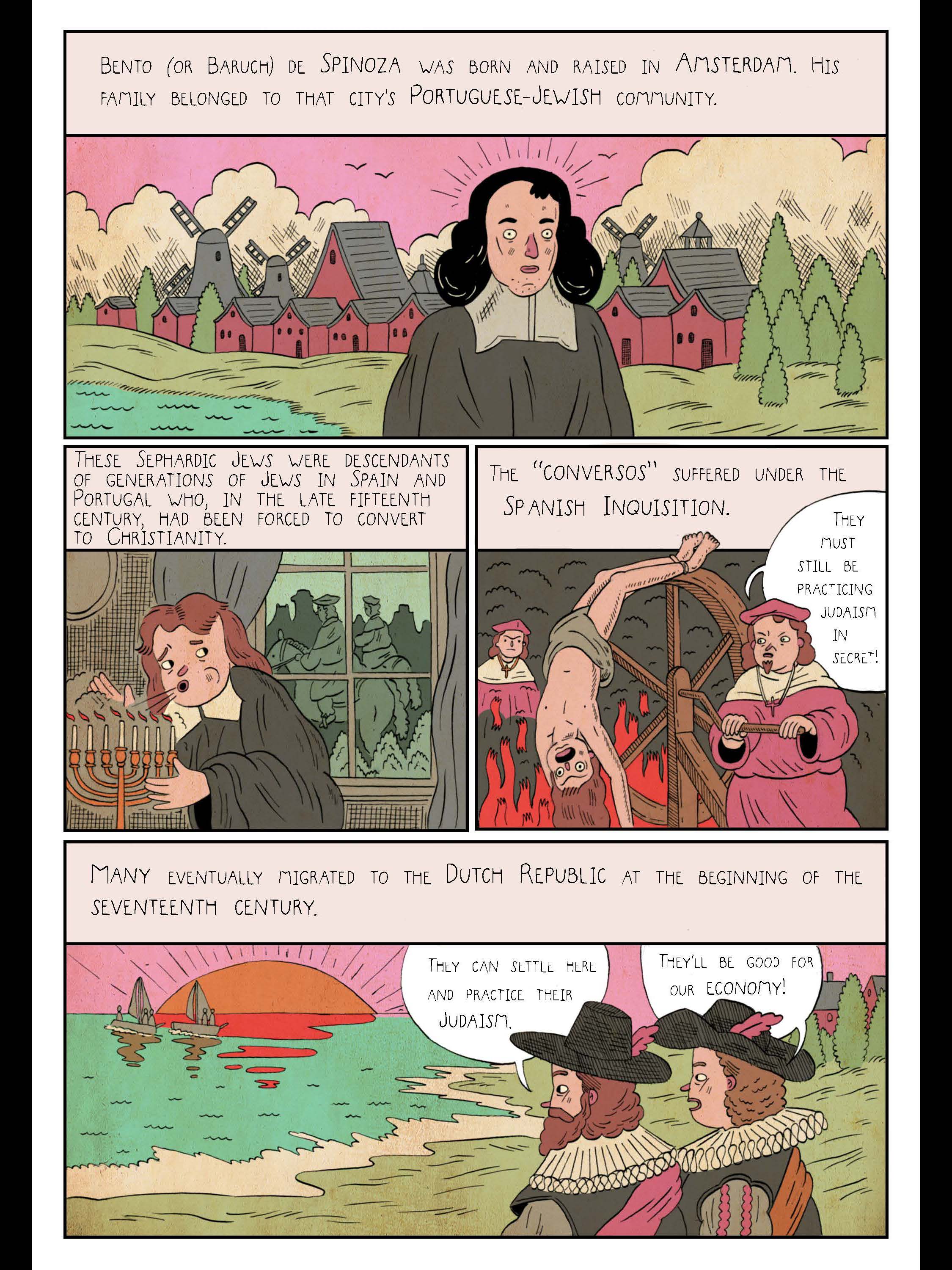

To give an idea of how we met those challenges, here are some sample pages. The first two come from the chapter on Spinoza. They present the background to Spinoza's life in Amsterdam among Jewish refugees from Spain and Portugal and some features of his philosophy, including his view that God is Nature.

Here we have the infamous "Defenestration of Prague", when ambassadors from the Holy Roman Emperor in Bavaria, seeking to settle things diplomatically with the breakaway land of Bohemia, were thrown out of a window by the Bohemians. This rude reception led to the Thirty Years War—and explains why Descartes's philosophical correspondent Elisabeth of Bohemia was living in exile in the Netherlands.

Ben took a good deal of care to make things historically accurate: what the philosophers looked like (from portraits of the period), modes of dress, even architectural details. But he also threw in some anachronisms, both to help explain conceptual matters and to inject a little humor. This page illustrates Leibniz's view that God chooses to create the best of all possible worlds.

Here is how Ben opted to illustrate the human soul (as a ghostly blue image of the body).

And this page illustrates Nicolas Malebranche's theory that God, as an omnipotent being, causally controls every single aspect of the cosmos.

Of course, we no longer look at the world with Cartesian or Leibnizian or Newtonian eyes. And yet, we still have some important lessons to learn from these early modern "heretics." For better or for worse, we are the heirs of the European intellectual traditions. And yet, we are now living at a time when science can be dismissed as "fake news," and when a propensity to trust the most ridiculous claims from sources lacking any credibility takes the place of tailoring our beliefs according to the available evidence and what seems truly reasonable. Under such circumstances, we can do worse than to reacquaint ourselves with these early modern thinkers and recall the importance of rational and empirical inquiry in the search for philosophical, political, and moral truth.

Were all of the philosophers in this book really “heretics”? Technically, only Giordano Bruno and Galileo were officially punished on this basis by the Catholic Church, while Spinoza was excommunicated for his “abominable heresies and monstrous deeds” from the Portuguese-Jewish community of Amsterdam. However, if the term 'heretic' refers to someone who, in spite of the risks, courageously promotes reason and truth contrary to what passes for conventional and popular opinion, whether it be in science, religion, philosophy, or politics, then the term is apt for most of the thinkers in this book. (Practically every one of the philosophers portrayed here had their writings banned by the Vatican’s Index of Prohibited Books.) We certainly could benefit today by having more "heretics" among us.

Steven Nadler is the William H. Hay II Professor of Philosophy and Evjue-Bascom Professor in Humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he has been teaching since 1988. He is the author of many studies on early modern philosophy. His most recent books are A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza's Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age (Princeton, 2011) and The Philosopher, the Priest and the Painter: A Portrait of Descartes (Princeton, 2013). His biography of Menasseh ben Israel will be published in 2018 in the “Jewish Lives” series by Yale University Press.

Photo Credit: Steven and Ben Nadler, All images excerpted from HERETICS! The Wondrous (and Dangerous) Beginnings of Modern Philosophy, via Princeton University Press. Copyright, 2017.