/ Why Do We Disagree with Science?

Subscribe

/ Why Do We Disagree with Science?

Subscribe

The Spoke continues its conversation with Wellesley College Professor Richard French, Louise Sherwood McDowell and Sarah Frances Whiting Professor of Astrophysics and Professor of Astronomy.

The Spoke: We learned recently that the nomination of this administration for the NASA director position is a politician, not a scientist. What do you think of this development?

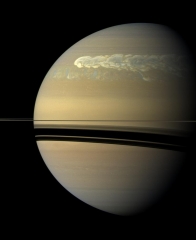

RF: It’s very troubling. I'm teaching a new class this semester, a seminar for first year students entitled "Critical Thinking in Science." One of my motivations for designing this course emerged out of the Cassini mission. With my students and guest speakers, we're exploring the fact that there are scientific truths that many people are willing to acknowledge, but there is also a strong resistance to paying attention to science when its results become politically charged. Trying to understand the biases, both political and personal, that we ourselves have, as well as the biases of people we are trying to convince, is really a critical skill, I think, for all of us today. So it seems very timely to me to have had a profound success with an international mission (Cassini) that spanned decades and twenty-something countries at a time when, I think, the status of the international scene is perilous.

The Spoke: What is the role of teaching science in a liberal arts setting?

RF: Distribution requirements often get students into astronomy classrooms. Indeed, without the distribution requirements we would not have anywhere as many students taking astronomy. I have no illusions that everyone is going to graduate from Astronomy 101 [a course that Prof. French has been teaching for years] thinking they want to be an astrophysicist. But I'd like them to emerge from that class with an understanding of why their roommate might want to, and with the sense that they have the capacity to speak intelligently about science.

I think that many Wellesley students, if you asked them the question, "Are you a science-type?" without any sense of guilt or shame, will say, "no, I'm not." What is interesting is that asking these same students if they are an “English-type” elicits a very different response. Students might get offeded by the suggestions that, perhaps, they can't construct a coherent paragraph, or read an essay critically, or construct their own arguments. There is a sense, among some students, that one just happens to be good or bad at science, in a way that does not seem present in other academic domains. So, my goal is for students, reluctant as they may be, to emerge saying, "I really can do science. I can see why it's fun."

And then when they graduate and move on to, for example, working in a non-profit that has to do with environmental science, and something technical comes up, they won't say, "don't ask me, I'm not a science type, ask Bob." I want them to be able to say, "I've had a chance to use that part of my brain, I can contribute to solving this problem."

The Spoke: What inspired you to offer this new class, the first year seminar "Critical Thinking in Science"?

RF: I been pondering for years the role that science, public science, and the interpretation of science plays in our society. I began my science career at Cornell with Carl Sagan as an undergraduate professor of mine. He encouraged us to think more deeply about conceptions and misconceptions of science. I've had that in the back of my head for a long time, wanting to teach a course about how to think critically, and how to exercise good judgement in science.

I haven't had the opportunity or the impetus until the recent political scene, which for me, made this an imperative that I couldn't ignore. Two particular experiences motivated me. First, I learned about the Fox News moon landing hoax documentary after it came out in 2001. I discovered that many of my intro astronomy students had watched it after taking introductory astronomy, and still thought we didn't go to the moon. This made me think that I was failing them. I realized that I may be teaching them all about stars and the moons, but I'm not teaching them the critical skills to assess whether (what I think of as) a ludicrous claim is really true.

Since this experience, I've dipped into discussions about critical thinking in my introductory courses once in awhile. But my second experience really solidified, for me, the importance of teaching critical thinking more explicitly. This second experience was the rhetoric around global warming during the 2016 Presidential election cycle.We are in a moment where somebody can call global warming a Chinese hoax, the EPA can have as its head somebody who doesn't think the environment needs protection, and NASA can have as its head somebody who isn't a scientist. These events suggest that it's time for us to really take seriously the exploration of what it is that makes people so resistant to what to some of us seem like self-evident truths. What I'm learning from teaching this course is that this is a common concern across the academy.

And one of the fun parts of crafting this course is being able to entice friends and faculty members to participate in this conversation with students with their own particular lens about identifying both biases and the validity of evidence. One of our guest speakers, from the religion department, will talk about about creationism, the young earth, and Genesis. We'll have a historian come and talk about early science reading. We'll go to the Library's special collections to look at the rich legacy of scientific ideas that turned out not to be right, including phrenology and water dowsing, among others. We'll have a statistician come to talk about how to lie with statistics. We'll have a philosopher come to talk about witchcraft, and the beliefs that led to the witch hunts of early modern Europe and New England. And computer scientists too! [Smiling at the interviewer, a computer scientist and guest lecturer in this class.] And today we're having a psychology professor coming to talk to us about our own biases. This is an important lesson because it's very easy to think that "I’m right” and “why don't those idiots listen to me!" It's very instructive to realize that we have our own impediments to understanding.

For me, part of the fun of this class is not only exploring a topic I've cared a lot about, but also having an opportunity to learn. Here is another example: a professor from the sociology department will come to talk about dealing with contentious issues. What happens when you have data in front of you that tell you in some objective fashion that a social truth that you think unassailable, turns out not to be supported by the evidence?

I'm looking forward to seeing how the course goes. But I also want to think of this experience as the beginning of a broader conversation across the faculty, where, at the end of the semester, we can brainstorm about taking the next steps, and bring some of these topics into our own classrooms. It's probably too ambitious but it's a lot of fun.

The Spoke: Then maybe that will be a perfect opportunity for us to catch up with you and everyone who was involved in your course at the end of the semester.

RF: I can't think of anything more fun!

This is the third and last part of The Spoke's conversation with Prof. French. Part one, about Prof. French's involvement in the Cassini mission, is available here. Part two, about Prof. French's thoughts on cooperation in science, is available here.

Photo Credit: Shutterstock. Catleski, "Astronaut on lunar (moon) landing mission." via Shutterstock.