/ Hillary Clinton's Campus Visit

Subscribe

/ Hillary Clinton's Campus Visit

Subscribe

After long lines in the cold, the crowd whipped itself into a triple-standing-ovation frenzy when Hillary Rodham Clinton stepped out onto the stage at her alma mater. This was our native daughter, come home to help us convalesce in a new and frightening world. And convalesce we did.

I felt better at the end of Hillary’s campus visit than I have since at least about 10 pm on November 8th. Or, more accurately, better than I had since I was picking up HRC campaign canvassers on November 6th. I witnessed a young white man jump out of a black pickup and start yelling epithets at the crowd outside the local campaign office. The volunteers yelled back “Love Trumps Hate.” The kid’s pickup had a huge Trump-Pence banner plastered across its tailgate.

Since then, I have thought a lot about “Love Trumps Hate.” I love that slogan. It thrusts love in the face of hate. It is a peaceful response to provocations that seek to incite violence. I hate that slogan. It is too peaceful a response to violent provocation. As Matt Irvin argues, “it may be that the best response to a troll is a swift kick (or punch).” Worse yet, it includes only Trump’s name. It links him with hatred, to be sure, but it still makes him the star of the show. We might imagine Hillary forcefully, yet lovingly, uttering it—or justifiably screaming it. But we have to imagine. Her name is not in it.

As Hillary strode confidently onto the stage, with a smile that could light up even a room that wasn’t full of her Wellesley sisters, she sought to quiet the frenzied crowd so that she and College President Paula A. Johnson (a fierce leader in her own right) could begin their discussion. The disconnect between this scene and the “Love Trumps Hate” slogan struck me. Scratch that: the disconnect between this scene and the way Hillary was discussed throughout the campaign struck me: the op-eds about why she is not likeable and the concerns that she—a former Secretary of State and then presidential candidate—is too much of a policy wonk all rose to the surface. These criticisms could not have been about the same person who was on stage.

Here, Hillary shared stories I had never heard before—and I pay a lot of attention to political media. She spoke of how she and Senator Chuck Schumer obtained $20 billion in aid for New York City after 9/11—not just that they did, but how they did. On the matter of her resilience and stamina, she frankly stated: “my faith path has kept me from spinning out in one direction or another” and she cited the influence of Jesuit theologian Henri Nouwen’s “discipline of gratitude.” Where were these stories during the campaign? Some were on display during the Democratic National Convention, but it seemed they were never loud enough. When Clinton talked candidly of Nouwen’s influence in her spiritual life at a New Hampshire town hall, Goldie Taylor’s post on the left-leaning Daily Beast talks of how this “window of intimacy…has, until now, proven elusive.” When Hillary is as frank and open as she can possibly be, many respond with whoa, I can’t believe this is happening. This dynamic troubled me for a long time, and the Wellesley visit has helped me make sense of it.

Hillary Clinton was relaxed, warm, and quite funny. She quipped about everything from her opponent “accusing” her of preparing for a presidential debate to how Russia’s outsized efforts to undermine her campaign were a “compliment.” This was fitting. Helena Halmari has identified rhetorical elements shared across successful political speeches, and humor is prominent among them. But it was not the Secretary’s humor that defined the evening. Instead, it was the very element that made her warmth, relaxation, and humor possible: an overwhelming sense of privacy.

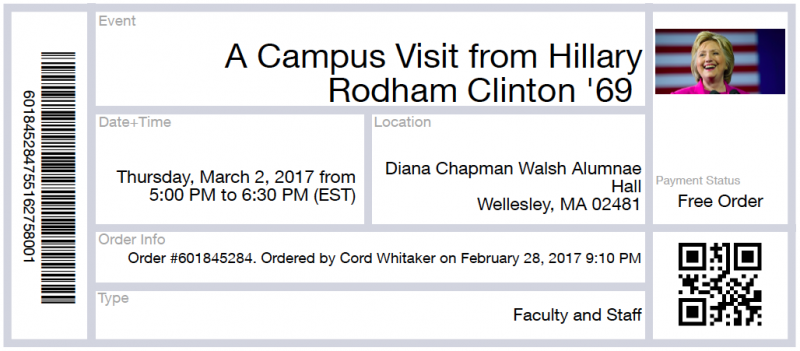

The visit was always bound to be exclusive. It was announced only days before it happened. It took place on the campus of an elite college with only just over 2,000 students. It was a ticketed event with limited seating. Nonetheless, it was to be an event for the entire College community. There was to be a livestream on Wellesley’s website. Until there wasn’t. It was announced that there would be no livestream after all. But surely there would still be video of the event streamed to the overflow area in the next building. Nope. There would be no overflow area either. The air on campus became more electric. What was she going to say? Would secrets be revealed? Would there be a call to arms?

Halmari says nothing about privacy as an element of successful political rhetoric. In fact, she identifies the opposite: lots of openness and collectivity (“Let us say to all Americans…,” “How can we help….” “We can talk about…”). But here it was: a growing sense of privacy ruled the day, charged the air, and then produced the most open and inviting version of Secretary Clinton many of us had ever seen.

Suddenly, it all made sense. Secretary Clinton’s visit to Wellesley was like “Love Trumps Hate.” It was consoling and powerful. It spoke into the darkness with resolve. But its heroine only reluctantly took center stage. She was willing to reveal her identity only to a point and to a select few. At my most generous, I can interpret the lack of Clinton’s name in the slogan—and her apparent comfort in a private setting—as living out 1 Corinthians 13:5. The text tells us that “love is not self-seeking” or, in another translation, “love does not seek the things of itself.” This does not accord with the political culture we live in. Though perhaps it should.

In the musical Evita, Argentine first lady Eva Peron’s character sums up her political aspirations in the lyric “You wanna know what you’re gonna get in me? Just a little touch of star quality.” This is not Clinton’s demeanor, even when she is commanding a crowd. Perhaps we ought to create a politics where a preference for privacy is not the same as hiding your light under a bushel. Maybe then Love might actually trump—no, overcome—hate. But since we in the U.S. electorate are collectively drawn toward the flashy bravado and perceived openness—however real or false, however admirable or reprehensible—of “star quality,” it seems we have, for now at least, gotten what we deserve.

Cord J. Whitaker teaches and researches medieval English literature and the history of race at Wellesley College. He is also the convener of the Albright Institute's Faculty Scholar Initiative. In addition to co-directing The Spoke, he blogs at www.inthemedievalmiddle.com and, along with his students, at www.whatisracialdifference.com.

Photo Credit: "Hillary Clinton Event Ticket," via screenshot, 2 March 2017.