/ Disenfranchised Voters Fight Back

Subscribe

/ Disenfranchised Voters Fight Back

Subscribe

We can thank Native Americans for democracy as we know it. The Iroquois Confederacy and its democratic form of government inspired framers of the U.S. Constitution—and sparked a global phenomenon. In the wake of the U.S. mid-term elections, we can thank Native Americans for standing up for democracy—and hopefully sparking another global phenomenon. Here is their story.

When the U.S. Supreme Court refused to intervene in a challenge to the 2013 North Dakota voter ID law disenfranchising thousands of Native American voters, I felt compelled to act. Regardless of party, all should agree that in a democracy everyone should be able to vote.

In 2012 North Dakota elected Democratic U.S. Senator Heidi Heitkamp by a slim 2,994-vote margin. Voters on reservations put her over the top. In 2013 the Republican-led North Dakota legislature sponsored a voter ID law that required an ID with a residential street address to vote. Previously, voters simply showed up and voted. Because most residences on reservations lacked street addresses, the legislation was an unequivocal voter deterrent.

The law was challenged, but on October 9th the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case and the law took effect. Irate at this outcome, I reached out to the North Dakota Democratic Party to join their legal voter protection team. Meanwhile the Native American non-profits Four Directions and Native Organizers Alliance swung into action to assign street addresses to all eligible Tribal voters and print photo IDs.

I flew to Bismarck and drove to the Standing Rock Reservation where I met others from the legal voter protection team at the Prairie Knights casino on election eve. Before dawn on election day the team scattered to polling places across the Reservation. A subfreezing gale whipped up from the prairie and the water bottle I’d left in the car was frozen solid.

On the way Porcupine I saw lawn signs reading “Standing Rock Will Vote”. I arrived at the Porcupine Community Center to find the election inspector Kathleen preparing materials, readying an optical ballot scanner, making coffee, and phoning young tribal election workers who had yet to show up. I was instructed to sit at a table across from the poll workers.

After a string of calls Kathleen finally filled all the election jobs, and the workers took an oath as required by the state. Another woman appeared, tasked with creating official Tribal ID letters on the spot for anyone who didn’t have a pre-printed ID.

After the polls opened, voters dribbled in slowly, all with valid IDs. Everyone knew everyone, and many were related. Another poll observer showed up from a non-profit—a four-month-old in his arms. After an hour only seven people had voted. I submitted my voter count to “the boiler room” in Fargo where a team of lawyers was stationed to deal with issues and tally votes throughout the day. Only one question came up on my watch regarding an ID that had expired. I was able to inform Kathleen that because there was no wording in the North Dakota Election Official’s Manual requiring an ID to be current, the expired ID was acceptable.

As things were sleepy in Porcupine, I was instructed to relocate to the Cannon Ball Community Center where voting was brisker, so I drove 39 miles northeast to the town of Cannon Ball.

As I entered Cannon Ball I passed a billboard reading “INDIANS WILL VOTE”, and circled around town until locating the community center. I entered a grander version of the voting space in Porcupine, and things were indeed livelier. I introduced myself to the election inspector, Blossom, and the other poll workers—all women. I joined five other poll observers seated at the far end of the room, two Republican men, two young law students from Colorado working with the same non-profit as the baby-toting dad in Porcupine, and a fellow Democratic Party observer, a woman lawyer from Bismarck.

Blossom ran a tight ship. Voters streamed in steadily—the polling place was never without voters during my five-hour watch. All but 12 of the 246 people who voted at the precinct presented valid IDs, and tribal letter IDs were created on the spot for the remaining 12. The outcome was that no eligible voter was turned away. The only voter who couldn’t vote in Cannon Ball that day was a young woman who had moved to Bismarck and had to vote there.

A high school teacher brought her voting-eligible students and returned later to vote herself. In the middle of the afternoon, the election workers offered hot soup to the poll observers, and a thoughtful young food truck owner delivered us hamburgers and thanked us for being there. I had been concerned that election observers might be greeted with suspicion, but we weren’t. Although some were curious about why we were there, everyone seemed fine if bemused by our presence.

In late afternoon, Blossom gave out the last pre-printed ballots and substituted photocopied ballots. With mild annoyance, Blossom described how she had warned the election officials that she would need more printed ballots, but they ignored her and relied on past precedent to estimate the number of ballets needed.

Throughout election day some 75 people scoured the reservation in sub-freezing temperatures and snow to get out the vote. Less than a minute before the polls closed the last voter, an elderly man, entered the hall, apologizing for having fallen asleep.

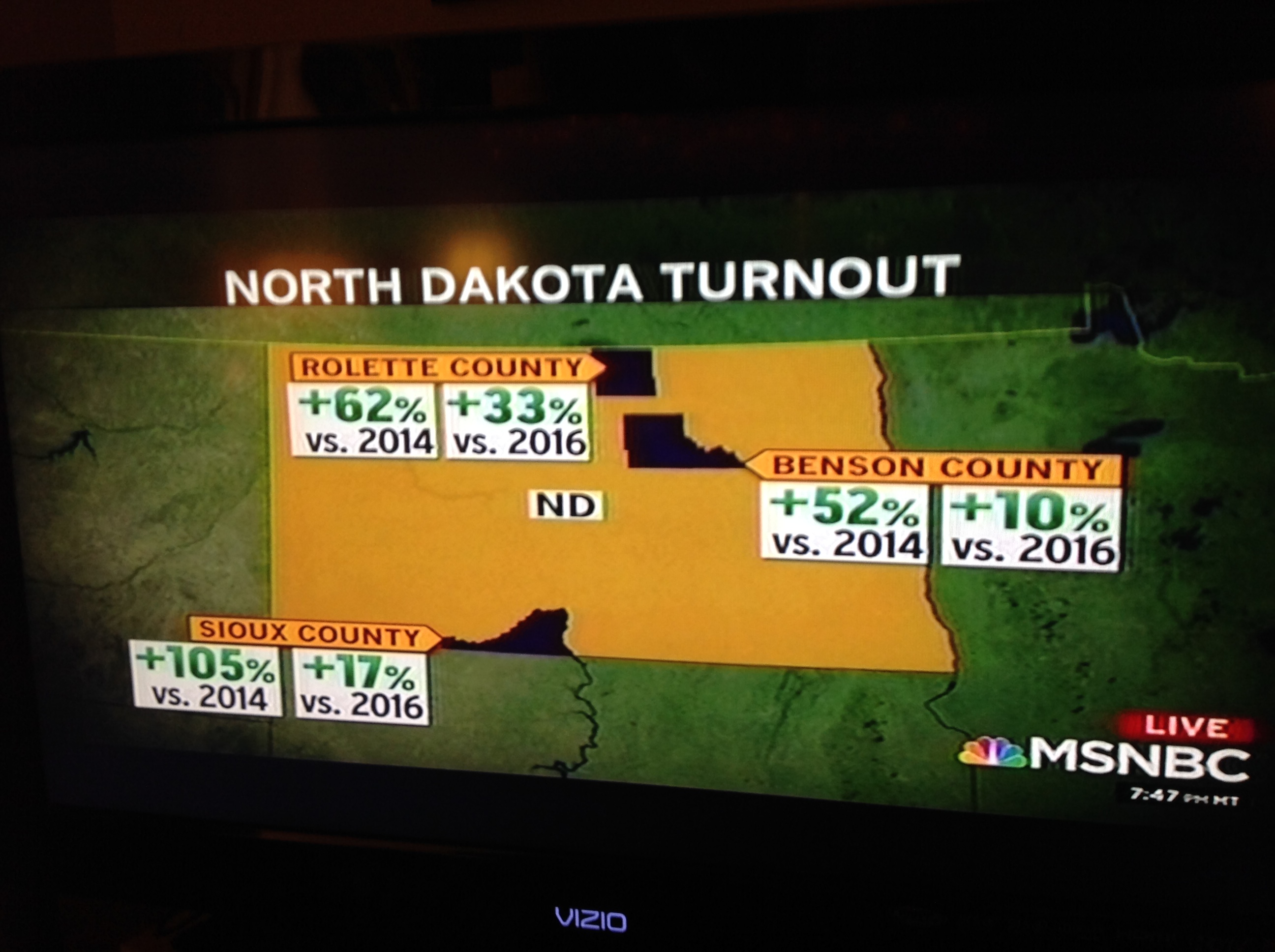

Voting throughout the day was smooth and professional—and voter turnout unprecedented. All who wanted to vote did vote. Claims of voter fraud that led to North Dakota’s voter ID law are unfounded, serving only as convenient cover for voter disenfranchisement aimed at gaining power. The Bismarck Tribune reported: “Unofficial results Tuesday night showed 1,444 people voted in Sioux County. The previous record was in 2016 with 1,257 votes.” Blossom said she had never seen such a turnout, and she had never before run out of pre-printed ballots. Porcupine also ran out of ballots, so things picked up after I left there.

Not only did North Dakota Republican legislators fail to disenfranchise native voters, they unwittingly fueled a movement that promises to endure and influence future elections. Native Americans rallied to fight voter disenfranchisement. What a privilege to witness and support their victory! The takeaway—disenfranchising voters is the best way to ensure voter turnout.

With countries as diverse as Brazil and Austria trending toward fascism, expect voter suppression to be more regularly selected from the box of tools used to seize and hold power. But in functioning democracies at least, citizens can use the vote to protect voting rights—not just for themselves, but for their fellow citizens. That’s what I saw folks working hard to do in Porcupine and Cannon Ball.

In a fitting close to this story, the prime sponsor of the 2013 voter ID law was unseated by a Native American woman, Ruth Anna Buffalo.

Image Credit (banner): “Standing Rock Will Vote,” Becky Wetzel.

Image Credit (in text): “Mid-term Voter Turnout on North Dakota Tribal Reservations,” Becky Wetzel.